Graeme Lay meets John Dunmore, the 92-year-old world authority on Pacific exploration – who has also written thrillers on the side, like the one about an assassin sent to New Zealand to kill Prime Minister Rob Muldoon.

Question: Who is New Zealand’s oldest living writer still publishing?

CK Stead? James McNeish? Gordon McLauchlan?

Answer: John Dunmore, 92, prolific author, esteemed scholar, respected publisher, his work recognised by two governments – he was appointed the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2001, and has also been named Knight of the Legion of Honour, and Officer of the Academic Palms (Academic Palms!) in France. He was promoted to Officer of the Legion of Honour in 2007, becoming only the tenth New Zealander to hold this level of the order.

He’s the author of over 30 books, and his latest, Chasing a Dream: The Exploration of the Imaginary Pacific has just been published by Upstart Press. It continues his lifelong fascination with the exploration and various discoveries of the Pacific.

As a post-graduate student at Victoria University in the 1950s, Dunmore came under the influence of the distinguished Pacific scholar and James Cook biographer, Professor JC Beaglehole. It was Beaglehole who pointed out to him that although the French role in Pacific history was very significant, it had been overlooked as an historical subject. He suggested that Dunmore work in the field of French Pacific exploration, during the eighteenth century in particular.

The student became a world authority. His biography of Jean-Francois Marie de Surville (1717-1770) won only the second-ever national book award held in New Zealand, the Wattie Book of the Year award in 1970, when it seemed our literature was fascinated with travel, distance, the awesome remote – second place went to Early Charts of New Zealand 1542–1851, and Philip Temple was judged third for his The World at Their Feet: The Story of New Zealand Mountaineers in the Great Ranges of the World.

Dunmore also wrote a biography of Louis de Bougainville (1729-1811), who traversed the Pacific and circumnavigated the world before James Cook. “Cook had English upper working class origins, Bougainville was French lower nobility,” he notes.

Also, both explorers took Polynesian men back to Europe with them, as living specimens of South Pacific manhood. During Cook’s second world voyage he took Omai, who joined the support vessel Adventure in Raiatea, to England, while Bougainville collected a Tahitian, Ahu-toru, and took him to France. Just as Omai became a celebrity in England in the 1770s, so too did Ahu-toru in France.

Dunmore says, “Ahu-toru was welcomed in Paris, including at the royal court. Bougainville and some members of the nobility looked after him and made him most welcome.”

Asked which of his many books he is most proud of, he says, “My French Explorers in the Pacific [two volumes, 1965 and 1969] feels important to me, because it was and remains the basic work, comparable with JC Beaglehole’s The Exploration of the Pacific (1935).”

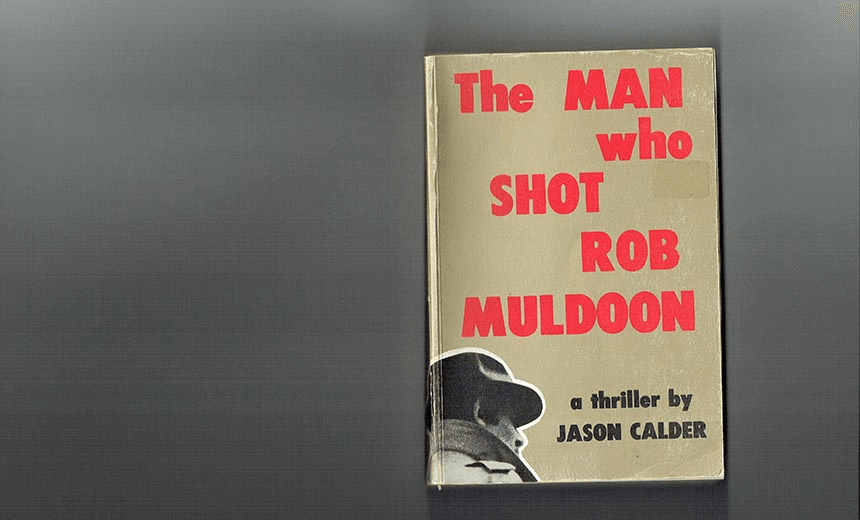

Dunmore became Professor of French at Massey. He also established the Dunmore Press, a major New Zealand publisher of academic texts. But there was another side to Dunmore, something less scholarly and dry – he wrote thrillers under the pseudonym of Jason Calder, most famously his 1976 novel, The Man Who Shot Rob Muldoon.

Above: Poor quality scan of old book.

The plot: A hitman is sent from the US to Wellington to assassinate the Prime Minister. Muldoon is oblivious to the threat; he merely grumbles about having to attend the opening of the Johnsonville Art Gallery. Fortunately a CIB detective called Carmichael gets wind that something is up. Dunmore introduces readers to him with a detail that subtly places him in New Zealand: “Chief Inspector Carmichael broke the stale Super Wine biscuit into small crumbs and laid them out along the window sill.”

*

His book Chasing a Dream is an overview of the way in which the Pacific first gripped the imaginations of Asian and European people, then the great ocean’s eventual charting – tentative and haphazard at first, then a more systematic exploration.

The Pacific’s immense size – it is the largest body of water on Earth – was one motivation for people’s curiosity. From west to east, from Malaysia to Panama, is 18,000km; from the Bering Strait in the north to the Ross Sea Shelf in the south is 15,500km. Long before explorers like Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake and George Anson entered and traversed Earth’s greatest ocean, what lay on the far side of the planet was a matter of conjecture and speculation, much of it flamboyant. For those beyond it, the Pacific was as mysterious and unreachable as the far side of the Moon.

Dunmore chronicles this fevered speculation in detail in the early chapters, particularly the myth of a Great Unknown Southern Continent.

Centuries before it was proved otherwise, it was presumed that lying within the Southern Hemisphere’s latitudes was a vast continent, to counter-balance Eurasia in the north. How could there not be such a landmass? If it was otherwise, the lopsided planet would flip upside down. Moreover, this great unknown southern continent, named Terra Australis Incognita, would likely to be the source of great riches, especially gold, which obsessed Europeans and Asians, and exotic peoples who some thought would walk upside down.

But long before the Chinese, Spanish, French, Dutch and English probed the apparently limitless Pacific, Dunmore points out that the Pacific islands were already settled, by people who had originated in south-east Asia, as early as 4000BC. They filtered into the Pacific from the west, sailing from island to island, advancing slowly, moving on when the population increased or inter-tribal conflicts forced them to move on.

Chasing a Dream documents the further exploration of the Pacific, by characters such as Hsu Fu, a Buddhist monk and a navigator. In about 219BC he was commissioned by the Emperor Shi Huang Ti, founder of the Qin dynasty, to enter the Pacific and search for the islands where legend had it grew a magic herb that ensured eternal life. So Hsu Fu set off in search of the islands where immortal beings lived. He returned reporting of having found the island, called Peng Li, but without the magic herb.

What the island’s ruler now needed, he told the emperor, were young men and women of noble lineage, and skilled artisans. After the Qin emperor agreed, Hsu Fu was given 3000 young men and women, plus the skilled artisans.

They all disappeared into the Pacific and were never seen again.

Above: A 92-year-old man.

Dunmore also writes about Spanish explorers, including Vasco Nunez de Balboa, who memorably sighted the Pacific Ocean in the 16ht century. Balboa’s discovery led to the epic voyage of Magellan, who in 1520 entered the Pacific at South America’s southern extremity, through the strait which will forever bear his name. After crossing the Pacific, Magellan was killed in the Philippines, leaving one of his men, Juan Elcano, to make it back to Spain, the first expedition ever to circumnavigate the globe. The human cost was horrendous – only 18 men out of Magellan’s original complement of 234 survived to reach their homeland.

Dunmore revisits his biographical subjects, Bougainville and La Perouse. The latter sailed north-east from Botany Bay in 1788 and his expedition just disappeared. His fate was not known for another 40 years. His ship had been wrecked in a storm off the island of Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz group of the Solomon Islands.

Later navigators from France did make it to these shores. I asked Dunmore what he thought New Zealand would be like today, if the French instead of the English had take over colonisation. Would it be all like Akaroa, where a French settlement began in 1840?

He doesn’t think so. He says, “It would possibly be fairly similar to what Quebec is today” – that is, one country with two western cultures. When the French flag was raised over Akaroa by a shipload of immigrants in 1840, the politicians in Paris had other things to worry about, rather than distant New Zealand. “I don’t think a French Aotearoa would ever have grown beyond what, say, New Caledonia is today, in terms of French culture.”

Chasing A Dream: The Exploration of the Imaginary Pacific (Upstart Press, $30) by John Dunmore is available at Unity Books.