Canberra’s offshore detention camps can be seen as an example of ‘necro-politics’, argues Janet McAllister.

This week, The Spinoff published Amnesty International’s piece calling for New Zealand to protest Australia’s offshore detention centres, and then The Guardian published mountains more evidence of abuse and atrocities on Nauru.

It costs Australia billions of dollars every year to violate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights so spectacularly. But simply pointing out the abuses and the cost, and hoping the powerful will fix things, hasn’t worked; it is not because those in charge are ignorant that the detention centres are still open.

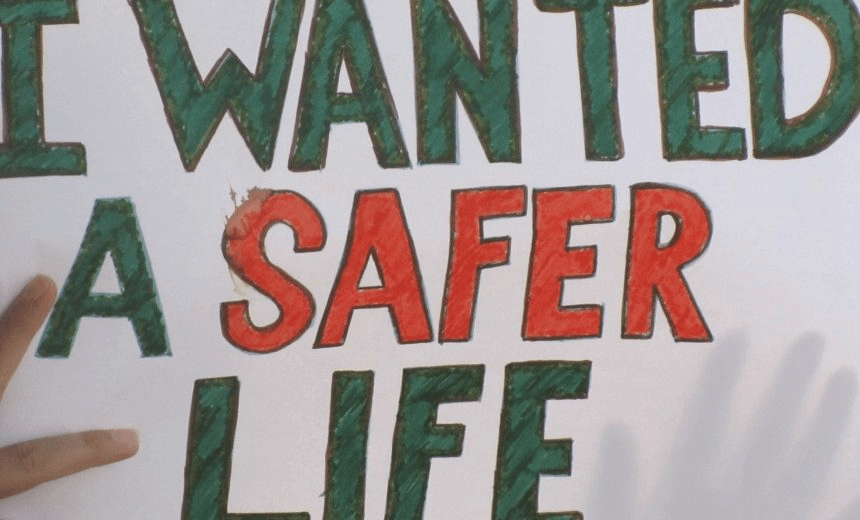

Instead, Australia’s concentration camps are an example of “necropolitics”, which is the creation of “death-worlds” in which people are kept in such conditions that they are made into the “living dead”, according to theorist Achille Mbembe. Colonisation and slavery are forms of necropolitics. The living dead are treated as zombies, to be feared and kept at bay, lest they eat the living. Australia’s necropolitics segregates to such an extreme that neither those living outside nor the living dead inside see each other, so neither really exists for the other.

“Civilised” Australia has form in flexing its necro-muscle against non-white Others, of course. While there are huge differences in its ongoing treatment of Indigenous Australians and asylum seekers, they are linked, and Australian necropolitics for both involves confinement and invisibility.

In the case of the asylum seekers, the Australian state is ambivalent (adding uncertainty to the death-world conditions). On one hand, the asylum seekers are to be ignored and hidden; hopefully they’ll go away. And yet necropolitics keeps them from going anywhere. On this reading, it would be better for the state if they were completely dead, if they had been drowned with their boats or if the regimes they escaped in the first place had done the job properly and killed them before they fled.

On the other hand, the asylum seekers have in at least one way become Australia’s useful slaves. Borrowing from anthropologist Shahram Khosravi, they are no longer just trapped on the border, they have become the border. Their incarcerated bodies – and the leaked reports of brutalities – are put to use as the insurmountable monument that politicians point to, supposedly in order to deter other would-be refugees – other border threats – from attempting to land. The asylum seekers brought-low are a vanquished menace, a reason to swagger triumphantly. Trump wants to build a concrete wall; Australia has built a zombie wall out of the living-dead bodies of the asylum seekers it abuses.