A new Christian party is touring the country, vowing to reshape politics in the image of their interpretation of Christianity. Alex Braae went to Marton to find out what the One Party had to say.

“Maranga mai!” called One Party leader Stephanie Harawira to the congregation in front of her. “It’s time.”

There is always a question with politicians about whether they have a hidden agenda. That’s particularly a charge that gets directed at politicians who have strong religious views. No such accusation can be made against the One Party, who have absolutely no interest in hiding their Christian faith.

Its message is a simple one. It is the only explicitly Christian party running for office at this election, and it wants to harness the demographic power of Christianity to become a political kingmaker. While other parties might contain, or even be led by, people of Christian faith, the One Party argues that it is the only party that will make serving God its abiding principle.

“We’re a Christian Party. We’re not just Christian values. Please do not water Him down to a ‘Christian value’ to suit the world,” thundered Harawira to the crowd. “We try and fit into a world to be politically correct. Just own your skin. We’re Christians. It’s OK.” She said when she talked like that, some people reacted “almost like they think we’re swearing at them”.

Over the past few weeks, the One Party has been on a barnstorming tour across the North Island, with Harawira speaking to multiple groups every day. I caught up with it in the town of Marton, where several campervans emblazoned with the faces of party leaders parked up in front of the Rangitikei College hall. Several local church groups from different denominations had joined together to host the meeting.

There were just under 100 people in the room, at a time when the region was under level two restrictions. The travelling group was welcomed onto the grounds with a stirring pōwhiri, and speeches that stressed in both te reo and English that Māori and Pākehā could become one family through Christ. The pōwhiri was followed by harirū, with both groups forming lines and sharing hongi with each other.

The One Party formed in reaction to what its members saw as the increasing secularisation of society. The protests at parliament over the removal of God from the parliamentary prayer was a highly formative moment, giving them a glimpse of what an openly Christian political movement might be able to do.

As various speakers in Marton attested to, events since had confirmed the necessity of forming a political party. Abortion was a constant theme, in particular the impression that law reforms had been passed during lockdown. They fear the looming assisted dying referendum. And in a telling grievance, huge offence was taken at churches being closed to gatherings at alert level three, while strip clubs could remain open.

The party’s structure reflects the belief that God should be above politicians. The political wing would provide MPs to parliament if they get elected. But on policy and legislative questions, they would be held to account by an Apostolic Council of religious leaders from various faiths and cultural backgrounds.

So far, the One Party’s media presence has been low, even by the standards of minor parties which almost always struggle for attention. That’s partly because it’s operating largely in Christian and Māori spaces, neither of which are heavily covered in mainstream outlets. That doesn’t necessarily matter to the One Party, which believes it can take its message directly to churches.

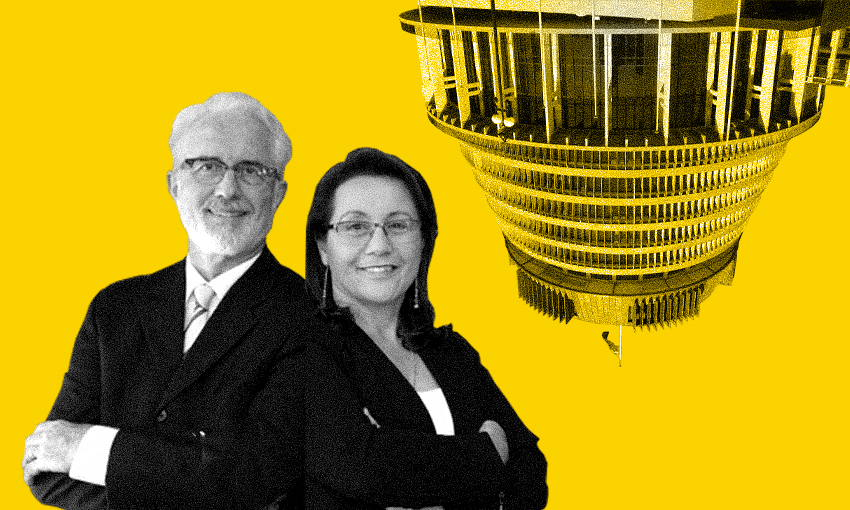

The concept of hīkoi is important to the party, which is heavily influenced by te ao Māori. Last year, a group who would later form One Party travelled throughout the country, visiting marae and building connections with churches. For co-leader Edward Shanly, they were his first experiences of being on marae at all.

In Marton, Stephanie Harawira told the audience she had been running a ministry called Pacific Pearls at the time. “And the lord said to me, get your name off it! There will be only one name, and it is the name this government dislikes. And you will go through this nation and lift up one name – Ihu Karaiti, Jesus Christ. It is a name that is not welcome in our land. It is a name that is despised and rejected.”

For many secular voters, the idea that they might end up living under a much more theocratic government could be deeply concerning. When The Spinoff asked her about that, Harawira denied that One Party had any intention of taking freedoms away from other people.

“All our policies fit along the lines of good values. We’re not here to take away freedoms – we want to push freedom, eh? Be free. So we certainly don’t want to push our religious beliefs on them. We’re not here to take away, we’re here to bless, and normal things like good education, clean air and clean water, I think that goes across the board for all New Zealanders.”

What kind of Christians are the One Party?

There are many ways to follow Jesus, some more demonstrative than others. Those in the One Party’s travelling group were devout and overt in how they expressed their faith – both in a religious sense, and their faith in the party.

In a cultural sense, the party leans towards the more pentecostal and evangelical end of the spectrum. There’s also a strong flavour of charismatic Christianity, with an emphasis on powerful oratory and a belief in the miraculous.

The concept of prophecy is deeply important to the politics of those running for the One Party. Candidates don’t speak of deciding to become politicians – they say they are given some sort of sign or message that it is their destiny. In Marton, an example of this came from Allan Cawood, who is running in Ōhāriu in Wellington.

He told a story about seeing his young grandson put his small shoes inside Cawood’s own shoes, and not understanding what it meant, except that the grandson would follow in his footsteps. Then later, he saw that grandson’s school report card, which included an otherwise totally out of context line about that grandson one day becoming a political leader. It fell into place for Cawood, who saw it as a message from God that he must run for office, to prepare a path for his grandson to walk in.

Cawood was one of several attendees who displayed symbols of Christian Zionism, wearing a Tallit (Jewish prayer shawl) during the pōwhiri. Another member played a shofar, an ancient horn-shaped trumpet used in Jewish religious ceremonies. Among some Christians, this indicates a belief in the state of Israel being part of Biblical prophecy, which heralds the second coming of Jesus Christ. Notably, the party is yet to provide a full account of its foreign policy platform on its website, except on the question of Israel – with which, they argue, New Zealand should have much closer ties.

Long devotional songs were performed at the start of the formal meeting. There was an almost meditative, polyphonic quality to how they evolved. Hands were raised, palms opened to the sky. At one point, the sound failed on a video explaining last year’s hīkoi, so instead a woman came to the front of the room and gave a performance of prophetic singing – a semi-improvisational form of musical worship in which the singer outlines the themes of what she is seeing as they come to her.

That hīkoi convinced Harawira that it would be possible for the One Party to appeal to all types of Christians, she told The Spinoff. “We watched that it opened the borders of denomination. We didn’t come together as Baptists, as Anglicans or Methodists. We came together just as people, who love the Lord.”

A particular group the One Party wants to draw into its fold is the Rātana faith, which is centred around the Rātana Pā to the west of Marton. Harawira noted how intensely politicians court that faith every year, because of the voting power of its more than 40,000 adherents. The church has maintained an alliance with the Labour Party for generations, and current Te Tai Hauauru MP Adrian Rurawhe is a great grandson of church founder Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana.

The greatest prize would be to make inroads into Catholicism, which is by far the largest single denomination in New Zealand. Catholics are, of course, already deeply embedded in all layers and institutions throughout society – for example, former PM Bill English is a Catholic. On pro-life issues in particular, they share many views with the One Party, but Harawira said their successes in advancing those causes had been few. “How’s writing letters working out for you?” she sneered rhetorically at one point.

The politics of the pulpit

One Party is adamant that New Zealand is a Christian nation, and should be run as such.

Harawira said that part of the reason the party formed was because other Christian politicians refused to do it. She expressed particular scorn for National MP Alfred Ngaro, who last year flirted with the prospect of forming a breakaway faith-based party.

“I went down there, and I placed the wero, a challenge, at the feet of Alfred Ngaro. You saw it play out in the media – every church was knocking on Alfred’s door. Lead us!

“I said to him brother, if you start a Christian party this is what we can do for you. We’re with you. Well that day, he didn’t pick it up. So I picked up my own challenge then and said get out of the way. We’re off.”

There are well over a million New Zealanders who identify as Christian, according to the latest census. But previous forays by explicitly Christian political parties have failed. The best result in living memory was the Christian Coalition, which in 1996 gained 4.4% of the vote, before the constituent parties fell out with each other. Other efforts have ended much less successfully. Still, One Party leaders are urging churches to ignore previous failures, and focus on the new project.

Harawira says she’s a politician with a deep understanding of numbers. She learned about electoral politics through working alongside Alliance, Māori Party and Mana Party activists, including the likes of Matt McCarten and Gerard Hehir. She’s the daughter in law of Ngāpuhi leader Titewhai Harawira, and the sister in law of former MP Hone Harawira, Titewhai’s son.

There has been little movement on an accord with the newly formed Advance NZ/NZ Public Party, despite overtures to the One Party in recent weeks. While co-leader Billy Te Kahika Jr is also a Christian, according to Harawira their respective parties’ kaupapa does not align, and the One Party doesn’t wish to stand under Te Kahika’s korowai.

An arrangement has, however, been made with the Destiny Church-backed Vision NZ party. Harawira said her party had a candidate ready to run in Waiariki, but pulled them back because it “didn’t make sense to stand against” Hannah Tamaki. In return, Vision NZ promised to not stand a candidate in Te Tai Tokerau. “That’s just called common respect, and you’ll find some parties work that way without losing their mana,” said Harawira. It is the only deal made by the party so far, with co-leader Shanly telling the room in Marton that they could abstain on voting for candidates in electorates the One Party aren’t running in.

Will voters actually turn out for them? That’s an immensely difficult question to answer, because voters are complex, and they choose their candidates based on a wide variety of factors. The One Party is hoping that the choice will come down to people putting their faith in God above all else, and the interpretation of that lining up with the party’s policies. Apostolic Council kaumatua pastor Te Hurihanga Rihari summed it up as he closed the Marton meeting.

“One thing that happened in the Bible – an event so profound, that the Lord went to his disciples and said look at this. It was an old woman, who put into the offerings coins – all that she had. The point is this: the Lord saw it,” said Rihari, over increasingly loud shouts of encouragement from those standing beside him.

“And I said, if my name and my tick is the only tick on that ballot paper, know this – the Lord will see it.”

Alex Braae’s travel to Marton was made possible thanks to the support of Jucy, who have given him a Cabana van to use for the election campaign, and Z Energy, who gifted him a full tank of gas via Sharetank.