He Kākano Ahau is a podcast by writer and activist Kahu Kutia (Ngāi Tūhoe) that explores stories of Māori in the city, and weaves together strands of connection. In this episode: Whakawāhine Māori talk about being accepted and finding space to explore identity.

I’m sitting by the window in a flat in Te Aro, Wellington. Opposite me is Kayla Riarn, pushing cigarette smoke out the window with a black lace fan.

“You go to any marae you see one of us whakawahine. We’re in the kitchen. We’re with the aunties. We are workers. We don’t argue about things on a marae. We get up and we do it. And we’re respected for it… Since I’ve been in Wellington I have worked in eight marae, as sole chef. I don’t get questioned.”

In this episode of He Kākano Ahau I’m talking to those who are decolonising gender and sexuality in Wellington city. Whakawahine might loosely translate as “trans woman”, but more importantly it’s a term that also takes into account Kayla’s whakapapa Māori. After all in te ao Māori, whakapapa is usually the first level of our identity.

Over a kapu tī, Kayla traces for me her whakapapa back into Taranaki maunga. She tells me that she had to find a lot of this out by herself. Her whānau moved to Tawa shortly after she was born. She’s been in inner Wellington since the 70s.

When colonising forces came to the Pacific there was a lot that changed for all of our cultures. Perhaps some of the biggest changes came with the introduction of the bible, which squashed out any ideas of sexuality and gender that weren’t cisgender and heterosexual. In te ao Māori today there is a heavy gender binary. Ira wāhine, ira tāne. They are still significant, but perhaps not as rigid as some may think.

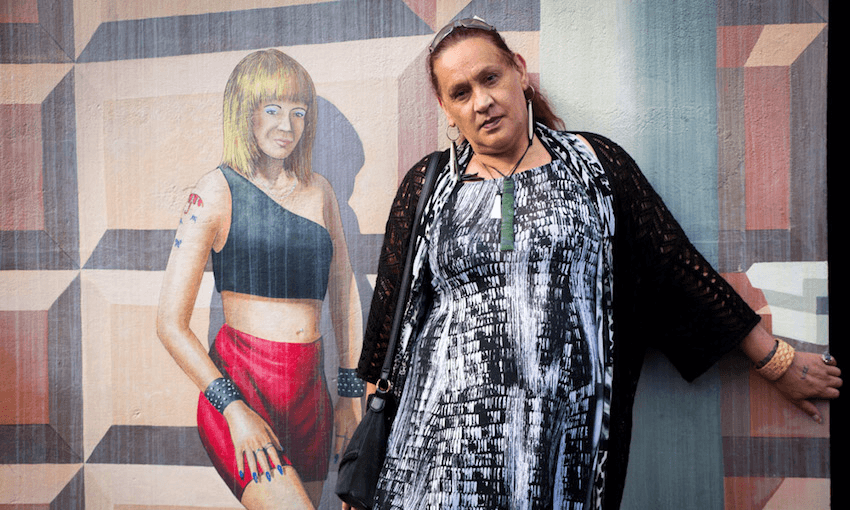

It’s a story that I don’t think has been explored in enough detail. I also wanted to talk to someone of my own generation who could speak to these experiences. I went to see Ariki Brightwell, who’s 30 years old. She grew up in Tūranga-nui-ā-Kiwa and came to Wellington to study at Massey. Today, Ariki is an artist and kaihautū for the waka that sit on the Wellington waterfront. Unlike Kayla, Ariki felt a lot of support from her whānau through her transition. Ariki also had good perspective on our history.

“What I’ve learnt from some of our kaumātua is that our people have always experimented or dived into our sexuality especially our gender. You know, that’s one of the main parts of our culture. It’s displayed on our carvings, the ure, the teke on our carvings, the form of a person on our carvings,” says Ariki.

It’s strange that we still think of takatāpuitanga as a modern thing when all across the Pacific are signs of a more accepting history. Whether it’s our Samoan fa’afafine, Cook Island akava’ine, Tahitian māhū.

If Wellington has a reputation of being “arty” and “liberal” and full of people who express themselves as individuals, I think that we owe some of that to people like Kayla, and other iconic trans Māori women like Carmen Rupe and Georgina Beyer.

Te ao Māori would not exist without the marae, that much is certain. But I have a hunch that the city might also provide something unique to our people.

Made possible by the RNZ/NZ On Air Innovation Fund. Produced for RNZ by Ursula Grace Productions