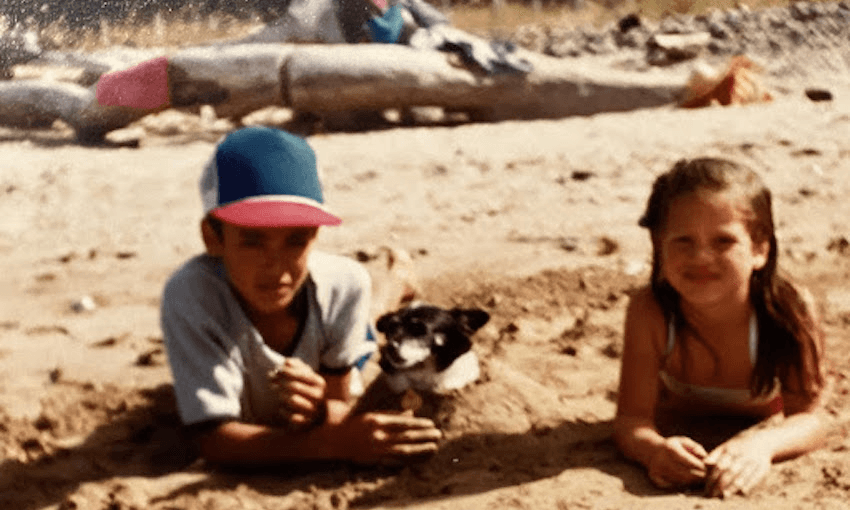

Nadine Anne Hura’s brother was different, like Māui. Equal parts curious, reckless, determined and brave, he couldn’t leave things alone. He needed to know.

I found my brother in a crowd of 60,000 people under the stars. It was 1993 and U2 was on tour at Mt Smart Stadium. If I said I remembered the song that was playing I’d be lying, but I know this much is true: I found my brother in a mosh pit when I wasn’t even looking for him. I was 16 and he was 21 and I hadn’t seen him in months. He was shirtless and slick with sweat, wasted and happy. He threw an arm around me as if he’d always planned it, this reunion of ours, and we danced together; man, how he loved to dance.

You ask of me to enter, but then you make me crawl

And I can’t keep holding on to what you got, ’cause all you got is hurt

It makes me wonder at the cosmic accident that determines who our siblings will be and where they will find us. One minute he was beside me, the next minute he was gone, swallowed up by the crowd. I searched and searched and searched but it was like he had never been. I wandered through the raised hands and the heaving shoulders and the pounding feet, looking for him. How can you lose someone that was right in front of you? All my dreams are of looking for my brother.

When we were kids we used to play teddy fights. His teddy had no hair and no name and fiendish button eyes. Mine, Big Ted, was fat and fluffy and wore unisex denim dungarees. My brother’s bald-orange street fighter would serve up two blows to the gut and a left hook round the chops and send Big Ted sobbing from the room. Despite the thrashings, Big Ted always came back for more. He wasn’t a masochist, he just loved the sound of my brother’s laughter. More of a giggle, really. Irrepressible, infectious. My brother laughed the way a pot boils. It made you want to tell jokes, just to hear it spill over.

Did I disappoint you?

Or leave a bad taste in your mouth?

You act like you never had love

And you want me to go without

When he was 15, he left home. I wrote about it in a story called The Pledge and it was published in an anthology of Māori fiction, but it wasn’t fiction. I wrote about my brother to press truth onto the page and because there are some things that only siblings can witness. This is my responsibility. Siblings are the fibrous tissue that connects muscle to bone, truth to memory.

As a child, he asked our mother: Mum, why don’t the stars fall out of the sky? Me, I never wondered about that kind of thing. I never questioned the givens. I was content to accept the stars had nothing to do with me. My brother was different, like Māui. He couldn’t leave things alone. He needed to know. My brother used to break things in order to see how they worked. He knew he’d get a hiding but he’d do it anyway. I see now that his hold on life was tenacious. The questions gave him purpose. The pursuit of knowledge was as ingrained in him as story is in me. He was equal parts curious, reckless, determined, brave. He was clever and fearless, often misunderstood. If he wanted to, my brother could change into a bird.

Have you come here for forgiveness?

Have you come to raise the dead?

Have you come here to play Jesus to the lepers in your head?

He used to say he didn’t feel Māori. He loved to eat boil up with dough boys and he’d drive all over the country and wade through swamps looking for watercress, but he always said he felt like a Pākehā trapped inside a brown man’s body. We would sit in his van, me with my can of Schweppes Dry Lemonade and him with his bottle of Kingfisher, and he would say that we were born into the wrong bodies, that he should have been the white one. I tried to tell him that no one is ever just one thing, and that being Māori feels like whatever it feels like if you have whakapapa, but he was better at physics than faith. Do you know what it’s like to regret the skin you’re born into? He is my sinew, too.

Well it’s too late, tonight

To drag the past out into the light

We’re one, but we’re not the same

When I left my marriage, my brother turned up with a trailer and heaved boxes and dragged furniture while berating me that I had too much stuff. He said that sooner or later I’d need to learn how to let go. I said that I liked my shelves. He said my shelves would end up owning me. I said fine, we can’t help being who we are, and this is who I am.

In my dreams I am calling his name but he’s on the opposite side of the car park, walking away. I ask him to come back. I tell him I wanna talk about it. “It’s too crowded,” he says, with a flick of his wrist. “Too much stuff weighing me down, Nadine.”

One love, get to share it

Leaves you darling, if you don’t care for it

He got lost, once, in the desert looking up at the night sky. He was parked in a campsite in National Park in his van, and when he looked out to the stars they beckoned to him to follow. He told me later that the land in the desert is like the surface of the moon, pocked with craters. He went down and up, down and up, following the shimmering river overhead. When he turned back to the van he couldn’t find it. It was July and freezing but his face was lit up with joy as he recounted what happened. He walked for three hours, hypothermia setting in, thinking this was the end. His laughter bubbled in his chest when he told me and I laughed along with him, not out of joy, not out of habit, but out of relief.

One life

With each other

Sisters, brothers

My brother wasn’t the only one who made pledges. We both had responsibilities. Before he left, he installed a new lock at my house and security lights with a sensor in the driveway. Some days I come home to the smell of boil up but there’s nothing on the stove, just a tūī in the kōwhai swilling nectar from golden blooms.

You say love is a temple, love is a higher law

Love is a temple, love’s a higher law

In Māori we say of our departed that they have gone to the stars. Our tīpuna reside there, above the horizon; guiding, beckoning, maybe even waiting. So now it’s for me to wonder why they don’t fall out of the sky.

“All endings are just beginnings,” he told me once. My brother was more Māori than he knew.

One love

One blood

One life

The night I found him the stars were brighter than they’ve ever been. He knew I would come, but he had already flown. There was no wind, not a breath of song. In all my dreams, I am looking for my brother. I wander the celestial crowds, blinking lights and shuddering breaths on bare skin. I walk in circles, turn, and then zig zag back the way I came. If he found me once, I think, he can find me again.