Essayist Nadine Anne Hura goes looking for one ancestor’s story, and asks what really lies underneath our monuments to war.

Small towns have big stories. I go around reading the plaques on top of rocks and plinths, memorials to the chosen, trying to decipher the story beneath the story. As I read, I almost feel like I can see the spaces where words have been withheld. Like knitting lace, a favoured technique where holes are deliberately made in a garment for the sake of beauty when admired from a distance, words on plaques can make you forget that it’s the gaps doing all the talking.

In Wairoa, it was the name Pitiera Kopu that filled me with questions. Etched into a white plinth in the middle of town, he was described as “a staunch friend of the Pākehā.”

If he was a friend to the Pākehā, I wondered, what was he to Māori? What did friendship with Pākehā in the 1860s look like? Who was Pitiera Kopu?

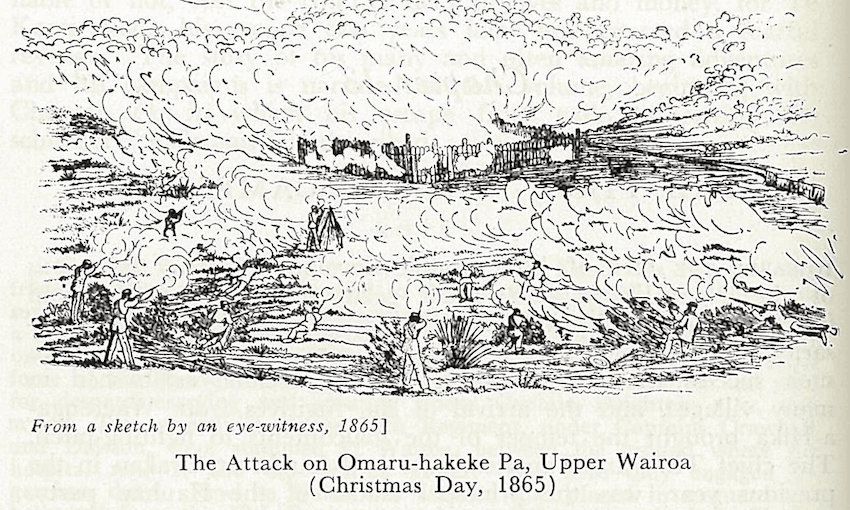

No clues on the plaque. Too many missing words. I crossed the road to the Wairoa museum and went searching. Inside, I found an exhibition commemorating the battle of Omaruhakeke. The exhibit takes you through the events leading up to the attack on an unfortified pā by Crown forces on Christmas Day 1865.

In the cool, quiet air of the empty museum, I tried to imagine it, firstly from the perspective of the children inside the pā:

Squeezed breath, fast-beating hearts, the rub of shoulders crouching close. Urgent sounds of weapons loading outside the papakāinga, just behind the toetoe bushes. Above their heads, a white flag with a red cross flying high.

From the perspective of the military settlers and loyalists gathering at the perimeter:

Stink and heat, itchy frustration. The attack was meant to happen the day before, but, being the Sabbath, they’d waited. There were 200 men in total and the sun was stretching out towards the afternoon like a long bolt of yellow cloth.

From the perspective of the Māori woman sent into the kāinga on behalf of the combined Crown forces:

Each step purposeful, the white flag she carried snapping in the gentle summer breeze. A lonely walk with a heavy burden – to deliver a message to the Pai Mārire within to surrender now and pledge allegiance to the Crown. Or else.

From the perspective of the faithful inside:

Dancing around the Niu pole while the voices returned, clear, unwavering. “We do not want to fight, but we will not give up our arms.”

And then there’s Pitiera Kopu, the “staunch friend of the Pākehā.” A loyalist, fighting on the side of the Crown. I can’t imagine what he felt at the moment the order was given to attack. I can’t conjure the thoughts that ran through his head. Reports say that he didn’t engage in gunfire directly at Omaruhakeke because he was urged to stay back in case he was confused for Pai Mārire and accidentally shot.

Māori, you see. Impossible to tell the rebels from the loyalists.

The trouble with words like ‘loyalists’ and ‘rebels’ is that they imply that there are goodies and baddies, winners and losers. In Māori, kūpapa is a word similarly infused with subtle intention. Short words that leave it up to the reader to differentiate between light and shade.

The trouble is, simplification too often fails us. The gaps hold all the clues. As far as Ngāti Kahungunu hapū were concerned, there were no ‘winners’ at Omaruhakeke. Everyone lost. Here was an iwi, torn apart by forces out of their control. They were whanaunga. They were related.

By the end of Christmas Day 1865 at least 12 Pai Mārire were dead, possibly more. Two loyalists as well. The remaining survivors were pursued into the bush, pelted by rain and bullets, while behind them the unfortified village of Omaruhakeke – said to be the birthplace of Ngāti Kahungunu identity – was destroyed and left in ruins.

As you enter the Wairoa museum, Pitiera Kopu’s picture is one of the first you’ll see. His eyes are tinged with light. He has a strong, angular jawline and thick, dark hair. He’s ruggedly handsome.

I wonder how he must have seen the unfolding events and his role in them. He was acknowledged, along with others, as a key leader and military strategist around these parts. He was a man of great influence among iwi, respected and revered by his people as well as the European settlers with whom Māori were living and trading – by all accounts – peacefully. I get the sense Kopu was a very politically astute man.

But he was also a family man. His wife was a Pai Mārire supporter. His son-in-law, too. His kinship ties to Pai Mārire ran deep. Life must have been complicated. Even more so as tension between the two sides began to heat up.

It was a miracle, really, that peace had lasted this long. Kopu and others knew that it was only a matter of time before the conflict in neighbouring areas spilled over and arrived at Wairoa’s door.

Battles had been raging in the North and the East and West for years, and land confiscated under the New Zealand Settlements Act was already being carved up. Wairoa was one of the last places in Aotearoa where the sovereignty of tangata whenua went unquestioned and unchallenged. In Waiora, Māori still ran the show.

To oppose the Crown and side with Pai Mārire would surely be folly.

But how to make the call and lead the charge?

I do not envy Kopu’s situation.

After Omaruhakeke, and following further clashes in the upper Wairoa that saw dozens more killed, imprisoned and executed, Pai Mārire, under the leadership of Te Waru Tamatea, eventually surrendered.

In a scene I find a difficult to picture, Kopu administered the Oath of Allegiance to Te Waru in a public ceremony attended by about 400 people outside the Clyde Hotel on the main road of town.

What must that have been like for these two great chiefs? Did they look each other in the eye? Did they press their noses together and let their breath intermingle?

Kopu stated that in taking of the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, Te Waru’s punishment would be completed. What he meant was, he wasn’t about to see anyone sent away to do hard labour on the Chathams like the Crown had done with other rebels.

That’s why the confiscation of two hundred thousand hectares of land in punishment for the battle at Omaruhakeke, almost a whole year after Te Waru took the oath of allegiance, is particularly cynical.

Of course, the Crown didn’t call it confiscation. The Hatepe Agreement used a much shorter, much more ambiguous word: ‘cede’. That short, dispassionate word left Te Waru and his people homeless and living in permanent exile.

When Kopu realised what was intended by the Crown, he was furious.

“I do not altogether appreciate the Pākehā method of conducting his warfare. Amongst us, when we had beaten our enemies, we made friends and lived together in concord and unity. But you (addressing representatives of the crown) are not satisfied with the men, you must have the land also.”

Just one week after that agreement was signed, before the ink was even dry on it, Kopu died.

Inside the cool of the museum in Wairoa some 150 years after all this happened, I absorb the futility of war generally, and more specifically, war as it impacted Māori in New Zealand.

No matter which side you were on, the conclusion was inevitable. The Crown was coming for the land, whether Māori surrendered it peacefully or walked straight into open gunfire. It’s a story that’s echoed in histories of battle up and down the country, making a mockery of the ignorant and privileged who insist that Māori need to “get over it.”

I am ashamed that as a nation we are still so selective when it comes to telling our stories. Too often, the history of the battles that were fought on this land become wrapped up in ‘Treaty settlement’ language, when in fact, the ramifications and reverberations of what happened in as a result of New Zealand’s land wars are still very much felt and seen today.

We could be doing so much better, if only in terms of how we talk about what happened. We may not be able to make peace with it, but perhaps we can make space to tell these stories in a way that has meaning for us not just politically, but personally. It’s important because although the battle has ended, the conflict is far from over. The question of how to live in this country peacefully is one that divides Māori still.

Some insist that the only way forward is to accept the system that’s been forced upon us and exert change from within. Others seek to remain outside, steadfast in their belief that surrendering is simply not an option.

I suppose by the old definition I would be classified as a loyalist. I am optimistic and pragmatic, and I believe in the power of social movements. The realisation that this probably makes me “a friend of the Pākehā” doesn’t so much hit me, as wound me a little. Because it does not capture the complexity of who I am. My whakapapa, the paths I’ve walked, the people I have loved, the lives I have lived. I want to say: “It’s more complicated than that.”

But there is no one else in the room to hear me.

Instead, I look at Pitiera Kopu, and he holds my gaze.

Epilogue

The last exhibit in the museum is a Pai Mārire flag. In a bizarre kind of symmetry, it turned up in a museum in Hawick in Scotland and was traced all the way back to the battle of Omaruhakeke.

It’s difficult to work out exactly how it got from Wairoa to Scotland, but I suppose it doesn’t really matter. The most important thing is that it was returned – uncannily enough, almost exactly the same time that Minister Finlayson came to town to offer an apology on behalf of the Crown, and to return parts of the land that was unjustly taken. It’s worth including the apology in full, here:

“The deed of settlement also includes the Crown’s apology [….] specifically for the war it fought against those members of the iwi and hapū of Te Rohe o Te Wairoa it deemed to be rebels, its unjust attack on the Omaruhakeke kāinga in 1865, the summary execution of prisoners in 1866, and the detention without trial of some members of the iwi and hapū of Te Rohe o Te Wairoa on the Chatham Islands from 1866 to 1868. These actions have led to lasting divisions between hapū for which the Crown expresses deep remorse.

The Crown apologises for the destructive impact and demoralising effects its actions have had upon the iwi and hapū of Te Rohe o Te Wairoa following its introduction of the native land laws, its relentless land purchasing programme, and its forced cession and effective confiscation of iwi and hapū of Te Rohe o Te Wairoa interests. The Crown’s apology also acknowledges the significant, cumulative, and detrimental impact its breaches of the Treaty have had upon the cultural, spiritual and physical well being of the iwi and hapū of Te Rohe o Te Wairoa and their economic development.”

And you know what happened next? As soon as five sites of cultural significance were returned, iwi and hapū gifted them straight back to the Crown for the people of New Zealand.

Mihimihi: This essay is based on material and information exhibited in the Wairoa museum, and in particular the research notes and essay shared with me by historian and curator, Nigel How. As with any story, there are always gaps, with light and shade given to different events and characters depending on who is doing the telling. This is true for me and the interpretation I have offered here. He kore he mihi mutunga e te rangatira.