Pipi beds die and algae blooms, but iwi are repeatedly told ‘there’s nothing to see here’, writes Graham Cameron.

When the Tainui canoe entered Tauranga harbour a millennium ago, it had the misfortune to run aground on a then prominent sandbar called Ruahine that sat below the waterline between Matakana Island and Mauao.

The Tainui was refloated and continued on its journey; the incident in which the Ruahine sandbar was central is remembered in a well known Tauranga Moana tauparapara:

Pāpaki tū ana ngā tai ki Mauao, i whānekenekehia, i whānukunukuhia, ka whiua reretia Wahinerua ki te wai, ki tai wiwi, ki tai wawa, ki te whai ao, ki te ao mārama.

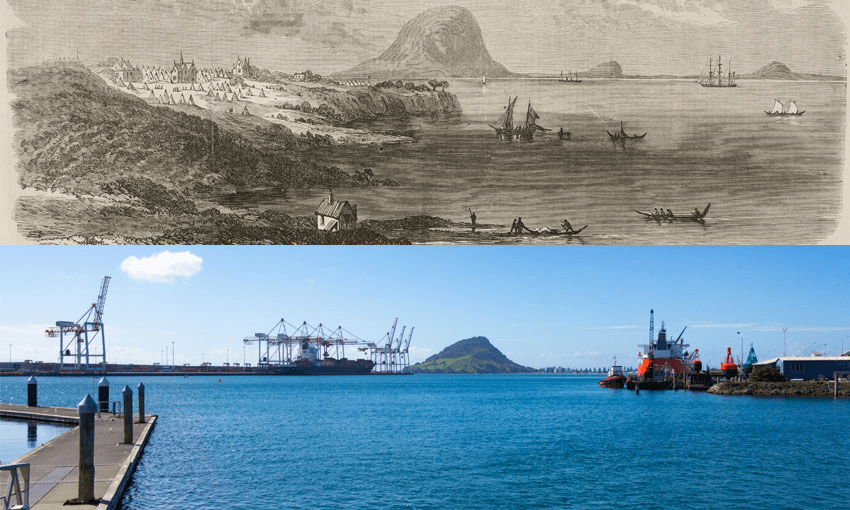

You may well hear that tauparapara at our marae, but you won’t see the Ruahine sandbar if you walk Mauao. By 1970 the sandbar no longer existed. It’d been destroyed in the process of widening and deepening the harbour and entrance for the establishment of the Port of Tauranga.

Our church is progress, and in the Bay of Plenty, the megachurch is the Port of Tauranga. Megachurches tend to not so much follow the law as create the law; the news that the Port of Tauranga has operated without a consent for stormwater for the past 27 years came as no surprise to tāngata whenua in Tauranga Moana.

The Port of Tauranga is a shining city on the hill. It’s the engine that drives almost everything here. Logs, kiwifruit, steel, palm kernel, coal and containers all flow in and out, like the lungs of our economy. Cruise ships visit in increasing numbers – loved by local retailers, despised by locals who remember a time when it was all for them.

The port is jobs, but not great jobs: casual, no longer zero hours but definitely not certain hours, de-unionised, long shifts and efficiency first. The port is jobs and the Port of Tauranga has kept bread on the table for many of our old people and our whanaunga since its inception.

For all intents and purposes, the Port is a religious idol in our privatised, profit, growth and market driven New Zealand. And like all true and holy idols, it’ll brook no opposition – it’s central to the power of the political and economic elite.

The Port of Tauranga is 54% owned by the Bay of Plenty Regional Council. The designation ‘regional council’ means that the 54% owner of the Port of Tauranga is also responsible under the Resource Management Act 1991 for managing the effects of using freshwater, land, air and coastal waters by issuing resource consents. For example, resource consents for stormwater discharge from ports.

Where parties fail to get a consent or follow the conditions of a consent, they can be fined or prosecuted. In 27 years of stormwater discharging into Tauranga harbour from the Port of Tauranga, the Bay of Plenty Regional Council has never fined or prosecuted the port.

The past 27 years are a series of false starts. The first consent lodged in 1998 never went anywhere because the port was slow in providing information requested by the council. The Regional Council then tried to couple the port’s consent with another for the Tauranga City Council. That failed because they couldn’t agree on who was liable for what discharge. Then it was revealed that Beca, contracted to do the consenting by the port, had lost the paperwork. The third application was lodged in 2013, but apparently nothing happened because of five years of consultation. We are now onto the fourth application. It is unlikely the port will be compliant this year.

When Radio New Zealand’s Checkpoint investigated this, everyone seemed disappointed with themselves, but not exactly up in arms. Stormwater doesn’t sound all that worrying. And the stormwater runoff from the Port of Tauranga is not notably toxic.

David Culliford looked into the stormwater runoff at the Port of Tauranga in his 2015 thesis ‘Characterisation, potential toxicity and fate of storm water run-off from log storage areas of the Port of Tauranga’. As best as anyone can tell, it’s all within acceptable limits, but Culliford’s work is clear that requires more research. The runoff from the log storage includes bits of wood, resins, chemicals and at times raw effluent. The runoff can slightly lower the pH of the water which is shown to affect the development and behaviour of marine life. There are periods of acute toxicity, particularly from raw effluent during storms. The runoff is detectable to over 60 metres, indicating there’s likely a wide spread of whatever impacts exist. At the moment there isn’t a good base of research as to the impact of dredging on sedimentation and toxicity. Which led to the conclusion that all is essentially well.

But sit at a table during a hākari at any of our marae, and we all know something is wrong. Pipi beds disappear. That’s not abnormal, but the increasing regularity and the size of the beds that have disappeared is a change. There are places where you don’t collect pipi anymore because they’re unsafe. There’s so much more sea lettuce than we ever had before. Algal blooms are normal; we are often told we can’t eat our kaimoana. Most people just ignore the warnings. And we’re told by our Port and our councils that it’s normal, that it’s seasonal, that it’s always been like this. It hasn’t always been like this.

The uncomfortable reality today is that the Port of Tauranga is too big to be allowed to fail and we can’t afford to stop its growth and development. You will hear few voices calling to limit the Port of Tauranga. Neither their majority shareholder the regional council, nor the local community given how many Mums and Dads have shares in the port, nor iwi.

Our iwi have not held the Port of Tauranga to account. Our lines of defence are quite literally in the sand; we have never halted anything the port wanted to do. If we are to be honest, we have always come around to an agreement with the port. The last instance was dredging that was consented in 2012 where the shipping channel was deepened by three metres to allow cargo ships with nearly double the capacity into our port.

This was only two years after the Rena had run aground on the Astrolabe Reef. As the consent was being considered, a cargo ship carrying logs lost power in the channel and threatened running onto the rocks of Mauao. The dredging at that time included the removal of a section of Panepane, a large pipi bed off Matakana Island.

Even in this instance, as iwi we followed our normal pattern: bold statements and threats of protests; submissions against the consents; the consent granted and challenged at the Environment Court; our agreement to a new oversight committee, some scholarships, the opportunity for shares, and research that will confirm there is nothing to see here.

All of us in the Tauranga Moana community bow our heads to our local religious idol. However passionately we love our harbour and our environment, in the end we are willing to accept the assurances of the Port of Tauranga that they have this under control. We hold these things to be true: the Port of Tauranga will protect the marine environment for us and provide excellent returns every year.

No stormwater consent can pretend to stand as a barrier to such an expression of collective faith. No fine can be allowed to tarnish the reputation of our regional economic saviour, washed clean by the millions of trays of kiwifruit. As we splash at the water’s edge this summer, we will look across to the white steeples of the cranes, and smile at our tamariki, warning them not to eat the pipi because of the algal bloom. And we’ll tell them, don’t worry, everything is going to be alright.