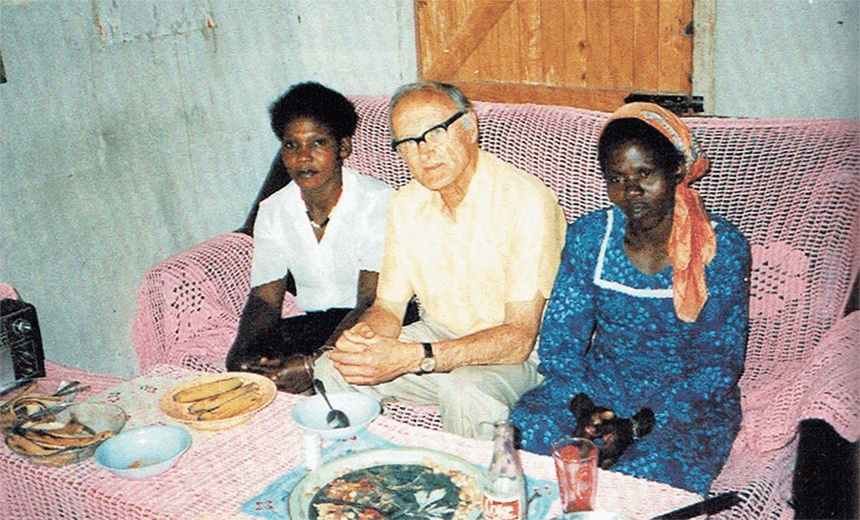

All week this week we revisit the life and writing of Greymouth author Peter Hooper (1919-91). Today: an excerpt from Hooper’s 1990 book Shade of the Mugumo Tree, a tender account of his journey to Kenya to visit Julius Kitivi, whom he sponsored through the Save the Children Fund. The two became close friends during Hooper’s month-long travels, but it ended in awkwardness and misery at Nairobi airport…

Johnson and Julius took me to the local market where Johnson and I drank a farewell couple of bottles of Tusker beer. Julius of course remained faithful to his Fanta. The side-road from the market back to the highway was unlit, black and shadowed by trees where silent figures often could be seen waiting for the unwary. Julius always took Johnson with him, his burly figure likely to deter any thugs. Recently a man had been attacked on the corner, robbed of everything but his underpants, and then, in response to his pleas, his attackers gave him coins for a bus fare home,

In spite of needing to be up early in the morning, Julius and I talked late into the night: about his prospects, his thoughts on possible marriage in four or five years time, his many friends, whether there was a chance that we would ever meet again. It was a time of sharing and reassurance, of gratitude that we’d been able to spend almost a month together. From the moment we met I don’t think I have ever more wholly delighted in the company of another. We seemed always in accord. Before we turned to sleep, after having talked ourselves into companionable silence he said simply, “I shall miss you.”

After several anxious awakenings I switched on the light at 5.30am. Within an hour we had left the house and were walking out to catch a city bus on the main road, Johnson carrying my case. He had to leave for work in a few minutes and at the bus stop shook my hand in the Kikuyu clasp signifying affection, before turning away.

We caught a workers bus into the city, standing all the way, and also on the airport bus, uncomfortably guarding my cases. We couldn’t talk, only cling to support as passengers pushed on or off, and I realised that I was beginning the series of mental and physical surrenders that would eventually return me to my own country.

At the airport we wasted time in the wrong concourse area before being directed to Kenya Airways. Julius beside me, I joined a long queue to pay the departure tax of 25o shillings. That was all the Kenyan money I had left, the remainder I’d given to Julius. The queue snailed forward. I reached into my trouser pocket to check the money – in a moment through all my pockets. In vain, I had lost my purse.

I’d been carrying a small purse in my left trouser pocket, my habit at home, although Julius had warned me it would be safer to keep money in an inside pocket, which I did for wads of notes. Julius was certain that I’d been robbed by a pickpocket on the bus.

There is a sense of unreality in such situations – “It can’t be happening to me.” One grasps at disbelief as a drowning man at the proverbial straw. Perhaps denial of the fact will reverse the situation.

An anxious hour ticked on towards the scheduled departure at 11am of my plane. Although Julius offered 250 shillings of the money I’d given him, the tax counter clerk would not accept Kenyan money. With a blunt “Departure tax must be paid in pounds sterling or US dollars”, he waved me aside and turned to the next passenger. Since I was returning through Australia I’d kept some Australian dollars intact while in Kenya. Annoyed that my carelessness was making Julius miserable, I hurried him away in search of a bank. A Barclays Bank was closed, a Kenya Bank would not change Australian into US dollars.

The hands of the clock crept towards the half-past. Worrying me also was the loss of my case keys in my purse. I had visions of customs officials forcing open my tightly-packed case and being unable to close it, so Julius and I searched among luggage until we found mine and I explained my predicament to a casual official who accepted my word, assuring me that the case would be placed safely on the plane. Heartened a little I decided to explain to authority at the barrier why I could not produce a receipt for payment of departure tax and turned to say goodbye to Julius.

Uncertainty, awkwardness, a sense of harassment arose between us, words failing to mask my annoyance and anxiety. For Julius, it was as though his country had turned against me, let me down, for which he felt a personal responsibility. What did I say? Did I say I hoped to see him again? I wanted to tell him that I loved him but could not. It was Julius who overcame the structures thwarting our goodbyes.

He looked steadily into my eyes and said, “Spiritually we shall always be together.”

I hugged him and we parted.

A postscript by Spinoff Review of Books editor Steve Braunias: In his Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Freud writes, “When a member of my family complains that he or she has bitten their tongue, bruised their fingers, and so on, instead of the expected sympathy, I put the question: ‘Why did you do that?'” It’s an old Freudian saw – there are no accidents – and it hasn’t much stayed the distance, but something about it lingers in Peter Hooper’s telling of his sad and wretched farewell to Julius Kitivi.

On the surface of it, the fact some asshole picked his pocket can hardly be defined as an accident. And yet wasn’t it his fault? Why was he so careless? The practice of carrying his purse in his left trouser pocket was a habit in New Zealand, but he’d been in the grasping Third World of Kenya for a month, and here he was on a crowded bus, “standing all the way”, exposed. Was there something in him that willed it to happen? Is this the Freudian key? Why did he do that? The “anxious hour”, the whole frightening charade of rifling through his pockets, then the new, separate anxiety of losing the key to his case: “I had visions of customs officials forcing open my tightly-packed case and being unable to close it”, he writes, as though the case were his heart and all would be revealed.

Pat White’s new biography of Hooper reveals the two loves of his life, both unrequited, both deeply unhappy; there is a tearful farewell to a woman called Louise on the front steps of Revington’s hotel in Greymouth. The miserable departure lounge scene with Julius plays out the unrequited affair all over again. It was what he knew about love, it was all he knew. He had to repeat it. “I wanted to tell him that I loved him but could not…I hugged him and we parted.”

Their late-night talk on “the chance that we would ever meet again” came to nothing. The book was published in 1990. Hooper died the following year. But there was enough time for a painful coda to their relationship, as Pat White reveals in Notes from the Margins. “He [Julius] felt Peter had transgressed in some of his comments as a guest in a foreign country, and especially after the hospitality gifted him while in Kenya…He [Peter] had mentioned family details taken from an early letter from Julius and made slight criticisms of the Askari police with whom Julius worked. These were actions unacceptable within the indigenous culture of Kenya. Peter did not send a draft to Julius before publication, an act that does have a glimmer of paternalism about it.”

Sad to think of Hooper, an old man in his last home, opening the envelope with bright Kenyan stamps and then reading Julius’s reproach. He began sponsoring him in 1976, when Julius was 13; he paid for his education, saved him from narrow subsistence, and they’d exchanged letters, formed a bond, spent a lot of time together in Hooper’s month in Kenya. And then 14 years after that first contact he writes a book about Julius and wouldn’t have had the slightest apprehension or suspicion that it would cause offence. The book is a love story. Like all of the love stories in his life, it ended in shattered pieces.

The excerpt from Shade of the Mugumo Tree: A Kenyan Journey by Peter Hooper (John McIndoe, 1990) is reprinted with the kind permission of the author’s literary executor, Brian Turner.

Read the rest of The Spinoff Review of Books series on Peter Hooper here.

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.