Victoria University Press is nominated for just about everything at tonight’s Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. How come? Is it a good thing? Or is it a depressing commentary on the sorry little state of New Zealand literature? VUP publisher Fergus Barrowman steps up for the revolutionary live email interview.

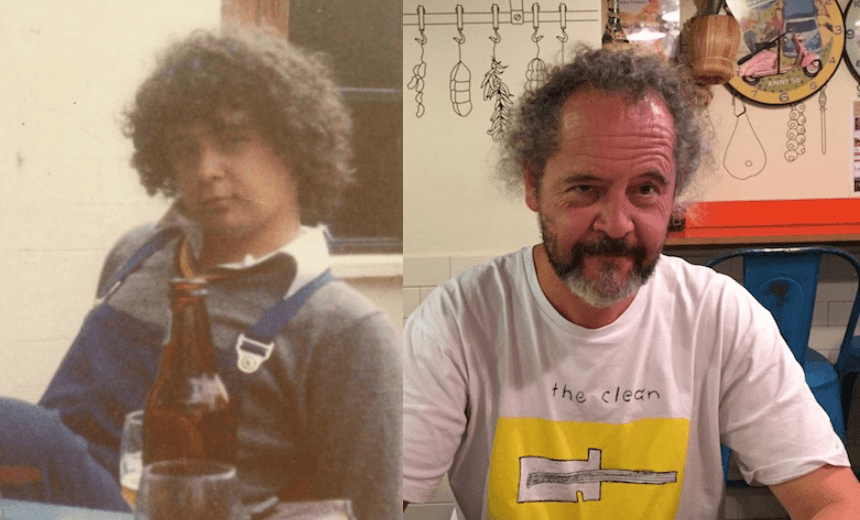

And the winner is Fergus Barrowman. The long-serving and interestingly hairstyled publisher of Victoria University Press is all over tonight’s Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, representing five authors in fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. No other publisher comes close to that kind of action at the awards but for that matter no other publisher has its snout in such a big fat state-funded trough. VUP is the literary civil service, all morning tea and the PSA, as Wellington as parliament and stairs. Plus it’s right next door to the Damien Wilkins School of Approved Uni Student Lit aka the IIML creative writing programme; the best of the best tip-toe down the corridor, tap on the VUP door, and Barrowman’s pleasant voice instructs: “Enter.” Eleanor Catton entered. Hera Lindsay Bird, Ashleigh Young and Catherine Chidgey entered, too, and they feature in tonight’s awards.

We conducted the live email interview – the practice which is revolutionising journalism as we know it, to the extent that we continually claim it is but without offering a shred of evidence – with Barrowman on a recent Wednesday from 8:15pm until 12:23am. He was at his Wellington home, where he can be found most evenings listening to insolent noise, which is to say he’s mad about jazz. His choice on Thursday night was Christoph Pregardien singing Mahler. The Spinoff Review of Books preferred to groove to out-takes from Crosby Stills & Nash; the vibe was set, and with instant coffee to hand, we began to compose our first email.

Fergus Barrowman, welcome to the revolutionary live email interview as pioneered by the Spinoff Review of Books. We need to speak to you Fergus because the heavy presence of VUP at the 2017 Ockham NZ Book Awards demands it. Five books shortlisted, and the three favourites to win fiction, non-fiction and poetry, respectively, are Catherine Chidgey, Ashleigh Young and Hera Lindsay Bird, all VUP authors.

There are various responses to this achievement but surely the first is to offer congratulations to you, as publisher, and to acknowledge that VUP is now the most important and most creative New Zealand publisher of New Zealand literature. What do you make of this achievement?

I’m trying to think of something smart to say but really the first thing is to say thanks for the compliment. We at VUP are very proud of these writers, and grateful we are that they’ve entrusted us with their books.

You’re welcome, but the brevity of your reply leads us to another response, which is to wonder whether the dominance of VUP at the awards is some sort of Bad Thing. There was this remark I wrote at the Spinoff, a few weeks ago, when the shortlist was published: “The narrowing of New Zealand publishing is such that the Ockhams may as well just cut to the chase and hold its national book awards at the VUP staff kitchen at 49 Rawhiti Terrace, Kelburn. Barrowman can put on the kettle. Ladies, a plate.”

Because, you know, the main commercial players are sort of staggering around, doing a lot of cookbooks and whatever, and there’s VUP, safe as houses, state funded, and the economics of it are crucial to the operation. Do you think NZ literature is getting close to being a one-publisher state?

In my private books awards fantasy we’re even more dominant. Where are Dad Art and deleted scenes for lovers and Mansfield and Me for goodness sake? Don’t you think we have been HELD BACK by successive judging panels’ reluctance to give too many awards, but this year it’s just been inescapable?

I do very much regret the way the tide has gone out on multinationals publishing NZ books. They did things we could never do as well, and they generated a lot of turnover in the local trade that benefitted everyone at every point in the supply chain. And I’m not sure it’s generally understood that the reason for withdrawing was that they no longer needed to be in New Zealand to sell international books here.

But I think you can see that with less mid-market clutter, when a book like Hera Lindsay Bird or Can You Tolerate This? or My Father’s Island catches on it gets more attention and better sales than it might have in the past. What’s most pleasing is that more often than not it’s the odd, unlikely book that does the business.

But you’re right too that ongoing support from you the taxpayer via the university is essential. It’s only in the wonder years of The Vintner’s Luck and The Luminaries that we haven’t lost money. Victoria University has been generous and far-sighted and has gained well-deserved bragging rights. And I don’t think public funding is going to become less essential to any art.

I hope we never have any kind of monopoly; think of the responsibility! But while the field is incredibly open – it’s never been easier to publish a book or start a publishing company – that’s only a small part of it. Books don’t turn into a literature without curation over time.

A fascinating reply on many levels, and yes I certainly do think you wuz robbed with the judges’ bewildering omission of the Sarah Laing book from illustrated non-fiction, though the judges of that category already proved themselves to be fuckwits with their omission of my book with Peter Black, The Shops.

Gee so it’s only with Elizabeth’s book – over 50,000 copies sold in New Zealand and over 100,000 copies worldwide, I just read on the internet machine – and Eleanor’s book that meant VUP hadn’t lost money? And yet you sailed on regardless, blithely in the red. The Act Party wouldn’t of allowed that to happen. But so with The Luminaries, and do please tell me how many copies that’s sold, was there a windfall that went back to VUP, and has that helped to allow you to fund what seem to be more books than ever?

I would of shortlisted The Shops; one of my favourite NZ photography books of all time.

The bragging rights are cheap at the price. But seriously, the university is also buying a significant cultural product and research output, which I have found even right-wing economists are capable of understanding very well.

Vintner after (bloody hell) nearly 18 years has sold over 60,000 in NZ, and The Luminaries after nearly four over 130,000. No idea how many internationally. In neither case did we get to keep our winnings, but the university was very understanding when we reverted to our usual financial profile. Actually what we did get out of The Luminaries was more editorial staff, which has improved my life enormously.

More people means we can publish more books. It also changes the way we work. I much prefer working with colleagues who have an overview of what’s going on and can contribute to publishing decisions and all the little decisions that follow. We use freelancers too, because I say yes to too much and have never learned the trick of a smooth workflow, but the richer in-house conversation is really transforming the Press at the moment.

I should ask you: when you preceded me as assistant to Pamela Tomlinson, did you see us going this way? I mean, we’re very much a publisher in the same image, same mix, same habits, just bigger – when I worked for Pamela, we were FTE 1.5 and published 8 books; this year we’re FTE 5.2, and are trying to publish 43.

I’m glad you mention Pamela. As we both know she was a wonderful person and an innovative publisher. I made a deal with her, that I’d go around to her house and chop her firewood in return for free copies of two fantastic VUP books, The Shirt Factory by Ian Wedde, which were short stories like no other short stories written here, and an incredible book about the prophet Rua Kenana. And I think her only staff was me, who she shared with the religious studies department. I didn’t do anything meaningful for either employer. Me and a girl who worked there would hive off to the Hunter building to smoke dope and pash. Her boyfriend came in from the Hutt Valley on a motorbike.

And then you turned up one day, this very nice guy, excessively young, and who knew then that you would go on to become publisher? And so – VUP back then was not at all like the VUP of now, and I certainly did not see it “going this way”. You were appointed in 1985 I think. That must have been around the same time Bill Manhire was creating the IIML empire which of course has revolutionised VUP.

These past few years in particular – has it struck you as something special going on? I mean Eleanor, obv, but also Hera and Ashleigh. What was it like seeing Hera’s book go off last year? And how long have you been aware that Ash was some kind of genius?

I remember you; you were the thinnest person on Kelburn Parade and you did not look like a student.

Pamela was wonderful. I was there for 20 hours a week, that was 1984, and we talked all the time and I don’t know how we got any work done, but we did. Or did we? – I remember it was only at the launch of Ian Wedde’s Georgicon that I realised we really ought to have put a blurb on the back cover. We talked about Pamela’s publishing experiences back in England with John Calder and Marion Boyers and Penguin, and all sorts of other things. It was a huge tragedy and shock when she died at the beginning of the next year, and I think I was frozen by grief. I dreamed about her every night for a long time and went to work every morning and got the books out.

Actually it was Bill who put me onto the job. I was a tutor in the English Dept not getting on with my thesis and he asked me to do a reader’s report, which I did fearlessly, then got me to help assess the creative writing class folios, then showed me the ad. The IIML and VUP have totally grown up together.

Being me, and having not gone anywhere else for thirty-something years, I’m much more aware of what hasn’t changed than on what has. Think of the excitement of reading unpublished writers like Barbara Anderson, Jenny Bornholdt, Dinah Hawken, Elizabeth Knox. Yeah, Eleanor Catton and Hera Lindsay Bird and Ashleigh Young are pretty good too.

But you’re right too it has changed in recent years: more people, more books, more risks paying off perhaps, but a different kind of buzz too. Perhaps that’s the great good fortune of who those more people are? I’m really lucky.

Ashleigh’s poetry – or rather a poem – was very warmly recommended to me by Greg O’Brien in 2003 (see Sport 30, the second Peter Black issue) and I believe I can credit myself with recognising at the time that she was an amazing writer who was going to take some considerable time to come out of her shell and conquer the world. The core of Can You Tolerate This? was in Ashleigh’s MA folio in 2009, and I wondered from time to time whether I should nag her to finish it, but it turned out of course that it took exactly as long as it was supposed to.

The Hera story is oddly similar. I would have published her MA folio as it was, and even embarrassingly put it on a forward schedule that got leaked, but Hera stubbornly kept it back till she was ready and she was absolutely right. And then I was momentarily afraid she had gone too far but fortunately by that time I’d learned how to trust.

What do you make of Eleanor? What sort of writer are we dealing with? And have you seen anything of the New Book?

I’ve read the 20-page outline of 80% of Birnam Wood and have signed a non-disclosure agreement so cant tell you any more than is in the press release.

I honestly think it’s too soon to say what sort of writer she is. It’s already clear that everything she does is going to be different from what she’s done before and that the pattern is going to emerge slowly. I remember the first time I talked to her after I’d read The Rehearsal it was quite an uncanny feeling – this very young woman who I thought I knew a little can see right through me and already knows everything I think – something like that. So there’s that, extraordinary psychological insight. But also the extraordinary pattern-making ability. I think that’s what The Rehearsal and The Luminaries have in common. You’re in awe of the surface, and also frozen into the surface, and then you fall through.

We’ve been talking about or referring to published VUP authors, and of course there are many, many others, Emily Perkins, Patrick Evans, Kapka Kassabova I think was yours?, and so on – but there must surely have been many, many more writers whose manuscripts you have had to regretfully decline over the years.

I came across this dialogue between you and Helen Heath in a questionnaire:

HH: What makes you put down a manuscript?

FB: If it sounds like literature.

What did you mean by that? When it’s all like belles lettres, and stinks of literature sort of thing?

Also, though, can I ask a supplementary question, about what you aren’t publishing: do you think VUP is too bourgeoise and staid or something to accommodate fiction which does more rough trade than most of your novels? You know, a Craig Marriner book, an Alan Duff, an author dealing in things from the wrong side of the tracks? Isn’t VUP all just a bit #middleclasswhitelivesmatter? Does its fiction list, actually, “sound like literature”?

Remember the AUP anthology of NZ lit? (How quickly we forget.) I had to like that book because it said I’d personally edited 1/8 of NZ literature. So yes the VUP list sounds like literature because after 30 year it pretty much is NZ literature.

I say no to things every day, and I don’t enjoy it. Even the least publishable manuscripts have been written with love and sincerity and a lot of hard work. There’s no science to it; I don’t have a checklist; but the “like literature” joke is meant to get at that feeling of someone who’s trying to reproduce an effect they’ve observed, but without feeling it from the inside. And it’s just as likely to occur when someone’s trying to write crime or wrong-side-of-the-tracks fiction as any other genre including literary fiction.

I get defensive about this. Apart from true genre, which would make no sense at all coming from VUP and wouldn’t find its core audience, there’s a pretty broad range of books there, and there’s not a lot that’s bourgeois about for instance Tracey Slaughter’s criminally-overlooked-by-the-Ockham-judges book. But that’s short stories so who notices? Would I have said yes to Once Were Warriors? I honestly don’t know. Stone Dogs? I’m afraid not; I didn’t believe it although I did recognise that it was a sincere effort.

Would you have published the bone people?

I like to think I’d have said yes, and that if I’d suggested edits Keri would have come back and said no and I’d have said sure we’ll publish it as is. But it’s easy to play this game.

Final question, because it’s now 11:22pm. What do you think is ahead of us in terms of New Zealand publishing? Will VUP, with its safety net and its guaranteed income, remain at the forefront? Paul Greenberg, legendary publishing veteran and distribution agent for Luncheon Sausage Books and other small presses, likes to say that print runs of even just 100 copies, or around 500, are where it’s at for books these days – it keeps the printing bill down, it’s a realistic figure to sell, it allows for purely creative endeavours. I like the sound of that, and independent publishers such as Titus, Beatnik etc are doing exciting things. But as our pre-eminent publisher, what do you think about the scene? Where is publishing likely heading? Is it state funding or bust? Or what?

I’m sure that VUP, and institution funded/aligned presses are going to be at the centre of things for a long time, and that’s no bad thing, because we can afford to take risks and support publishing programmes over time and are also not overly beholden to recently-successful authors which is also a useful thing. And I don’t think there’s any real sense in which we stand in the way of punk rebel publishers springing up. There’s also some astonishing young editorial talent, especially inside VUP but elsewhere too, which means I can contemplate slipping sideways out of the picture with no anxiety.

Paul [Greenberg] is absolutely right. Most of our poetry first print-runs now are 300; fiction 500. At least half of those reprint, and there aren’t many unsold copies of the others. Other boutique publishers have even smaller numbers. It’s a publishing model that’s never going to be profitable, but it’s sustainable if everyone’s eyes are open. And it’s only one more step to Hera Lindsay Bird or Can You Tolerate This? Which is great isn’t it: there have never been more small, odd, perfectly individual books published all over the world, and it’s never been easier to get them from New Zealand or wherever.

But I don’t think multinational publishing is coming back to NZ in a hurry.

You say, “I’m sure that…institution funded/aligned presses are going to be at the centre of things for a long time” – but it didn’t work out that way for Te Papa Press, did it? It got well and truly fucked over. Even though it was central government, an institution, the bottom-line imperative prevailed, and it got vandalised, gutted, stripped.

That was bad, and it could happen to anyone. Could it happen to everyone? Of course – this is why bigoted and illiberal governments are much more dangerous than globalisation and big corporations will ever be. Megapublishers have no interest in smaller publishers except very occasionally as sources of new talent they might exploit; they certainly don’t see us as threats that need crushing.

Actual final question! I want to ask you what it all means. Literature and that. Seriously, genuinely. Put it this way: was Cyril Connolly right, do you think, when he said that the purpose of the artist is to create a masterpiece? And what, then, is the purpose of the publisher?

I’m all in favour of masterpieces, but wouldn’t it be exhausting to read only masterpieces? I think I have a humbler idea of writing as something that many people do, from which will emerge a great deal of work that is useful and sustaining in its time and place, and some work that will go much further and last much longer. I’m happy to have a job identifying work I think is good and helping it reach its potential. Also publishing is reading and it’s allowed me to remain the child who once discovered reading.