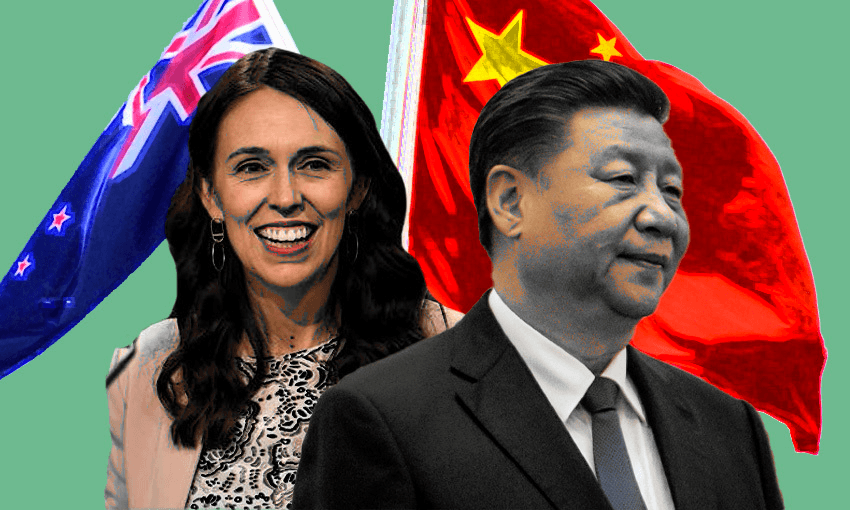

Unlike Australia, New Zealand tiptoes around criticising China, fearing a trade and investment backlash. But are those fears really justified?

In this episode of When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey talks to Natasha Hamilton-Hart from the University of Auckland business school and Sam Roggeveen from Australia’s Lowy Institute about why we should stop worrying about trade and start standing up to China on human rights abuses. Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

It was an act of group think we’ve become used to.

First, a nationwide shrug, and then a collective wobble of the head and a sigh that said “there’s nothing we can do about it. We’ll just have to suck it up and keep our mouths shut.”

On the eve of a momentous debate earlier this month in parliament over whether to adopt a motion declaring China’s oppression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang a “genocide”, trade minister Damien O’Connor said out loud what everyone was thinking, but rarely ever says.

“Clearly the Chinese government wouldn’t like something like that. I have no doubt it would have some impact (with trade). That’s hardly rocket science,” O’Connor told reporters as it became clear a parliamentary committee would eventually pull the g-word from the motion to spare our diplomats and exporters a nervous few weeks and months.

Opposition leader Judith Collins reflected that bipartisan timidity on China and fear about any fallout on our exporters. Asked if New Zealand was beholden to China, she said: “If you’re looking at trade, at the moment, clearly we are (beholden to China) in terms of trade. So 29-30% of our trade goes to China.”

So New Zealand’s representatives on the global stage pulled out the offending word and trudged on without too much complaint or debate. We have reflexively ingested the notion that this is just the way of the world, where we are small and weak, and China is huge and getting much stronger.

Is a painful backlash really such a given?

But is that collective view – that we have no choice but to tug our forelock and “not mention the warʻ – actually right?

Would our exporters really lose out if Beijing chose to punish us by reimposing tariffs on our meat, dairy, wool, fish and logs, or held them up at the border with all sorts of non-tariff barriers?

And would our companies with joint ventures and investments in China, or those with assets in New Zealand owned by Chinese investors and companies, be hurt by Beijing giving us the almighty cold shoulder? Would our phone calls and meeting requests suddenly go unanswered and would our accounts suddenly run dry?

I think it’s worth challenging both of these commercial and geopolitical items of faith.

Australia’s example is a good one

We don’t have to look far to see how China’s passive aggressive and just plain aggressive trade backlash against a nation has affected its exporters. A widely held view in New Zealand political circles is that the Australians were crazy to call for an investigation into China’s withholding of information when Covid-19 initially broke out in Wuhan in December of 2019 and January of 2020. The Australian government’s decision to unilaterally cancel the Victorian government’s Belt and Road agreement with Beijing seemed provocative at the very least.

Suggestions from senior Australian ministers and officials in recent weeks that our Trans-Tasman neighbour may even have to go to war with China over Taiwan or the South China Sea seemed reckless in the extreme.

Here at home, we winced and worried as China progressively imposed tariffs and blockages on Australia’s wine, barley, sugar, beef, lobster, cotton, coal and timber exports over the last year. Surely, we thought, these big swinging Australians are dicking themselves over and we could be next if we step out of line too.

But a closer look shows Australia has not suffered much at all. This is partly because these exports have been diverted to other markets and global prices have remained high. As is the way in the world of commerce (and tax), ingenious companies and traders find a way to match supply and demand, diverting and re-routing products in ways that mean China’s consumers eventually get what they want.

Secondly, Australia has suffered little because China has not dared to try to restrict Australia’s largest export: iron ore. The red and brown stuff is the crucial ingredient for the steel that underpins China’s infrastructure and manufacturing driven economy. Australia is its main supplier of iron ore, in part because supplies from Brazil have been restricted in recent years by two catastrophic dam collapses at the biggest mines.

There’s nothing left to lose in the JVs

The other fear in New Zealand is that China would expropriate or destroy the joint ventures that some New Zealand companies have inside China, and that Chinese firms or investors in New Zealand itself may pull out.

Neither of those fears are substantial now. The joint ventures have been wrecked anyway, and this is not unique for international companies working in China. They are often forced to join up with local companies and hand over their intellectual property, only to find little but an unenforceable shell and empty accounts when the heat goes on.

Fonterra has lost between NZ$1b and NZ$2b over the last 15 years with two major joint ventures in China. Its Sanlu venture unravelled and then imploded in 2008 when the Chinese partners laced its infant formula with melamine, sparking the most almighty food scare and dozens of injuries and some deaths.

Then Fonterra started building massive dairy farms in China and eventually formed a new infant formula distribution joint venture with Beingmate, in part because it felt it needed to demonstrate its commitment to China in the wake of the botulism food scare. That episode cost previous CEO Theo Speirings his job and has been liquidated by his successor Miles Hurrell.

Cloning Zespri’s golden goose

But the most extraordinary example in recent times of an unreliable and downright abusive partnership between NZ Inc and China Inc has been around Zespri’s experience with its lucrative SunGold variety of kiwifruit, which it owns the intellectual property rights to.

A New Zealand resident born in China, Hayao Gao, took cuttings of SunGold from his orchard near Opotiki to business partners in China in 2012 and within five years they had planted 4,000 hectares of SunGold there, which is about half of New Zealand’s total plantings. All of this breached China’s own intellectual property laws, but was unenforceable in China’s opaque and uncontestable legal system.

Gao was prosecuted in New Zealand and found guilty by the High Court of theft in February 2020. He was ordered to pay Zespri NZ$15m in damages. But now Zespri is looking at helping the pirate growers in China to improve their crops and marketing so as to negotiate at least some clip of the ticket. It has judged that if it can’t beat the pirates, it should train them to be more civilised.

New Zealand’s kiwifruit regulator objected earlier this year to the trial, as have many of Zespri’s owner-growers. A vote will be held in June. The question being asked is: will New Zealand be taken for a ride again?

President Xi’s national project

So many New Zealand and global companies have been taken for a ride in China that the gloss has come off all the hopes of the early 2000s that China would join the rules-based global system of capitalism and trade that treated every company and shareholder as equal, regardless of nationhood or Governmental support.

America’s pivot to contesting with China, rather than partnering with it, is not some sort of Trumpian reflex against foreigners. It’s a building movement that many New Zealand companies and traders have been quietly sympathetic too.

The Australians have not been so quiet. It has not hurt them much. We should consider expressing our core values on human rights without the fear of an economically damaging backlash.

Those fears are overplayed, and our naively trusting approach to China Inc also needs to be put back in the box they were built around in the immediate wake of the 2008 Free Trade Agreement, and before the 2013 ascent to power of President Xi Jinping.

He has demanded Chinese firms and owners comply with the nation’s directives around security, independence and the national interest. They must also include a Communist Party member on their boards and advisory committees, to ensure they toe the Party line. The defenestration of Alibaba’s Jack Ma this year is proof that President Xi’s authority will not be challenged by anyone, even those with power and money inside China, let alone outside.

China under President Xi has become a bully state, but is also hurting itself and its own people with tariffs and restrictions. New Zealand should not cower in front of this sort of bullying, and should be more confident that it will prosper in the end.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.