Outsized economic growth is becoming more of a threat than an opportunity in the Mediterranean tourist Mecca and New Zealand should take note, writes financial planner Chris Lee.

Any business – indeed, any country – that does not carefully consider ‘right sizing’ is at risk of failure caused by inappropriate, unsustainable growth.

Ask former Fletcher Challenge CEO Hugh Fletcher. If he had dismounted from his high ivory horse he would today recognise the havoc the company created when, under his leadership, it sought to diversify and scale without heed to its limited capital base – including human, financial and intellectual capital.

Fletchers all but collapsed through misguided pursuit of growth, motivated by delusions of global grandeur.

Perhaps Fonterra would admit to the same failings, as might Brierley Investments, Equiticorp and most of the childishly run property companies of the 1980s.

Today New Zealand needs to apply its mind to what appropriate levels of growth are. That’s the case not just in areas like dairy farming but also in tourism, where exciting but uncontrolled growth may not be our greatest opportunity but our greatest threat.

Will our country eventually turn off the tap of ‘free’ 15% GST revenue from tourists, by failing to maintain the very standards that attracted those visitors?

In the past I heard accolades from tourists that included words like clean, green, friendliness, low crime, empty roads, cheap, good motels, great food at affordable prices, low cost national parks and tolerance of foreigners. I am not sure I have heard those words so often in recent years.

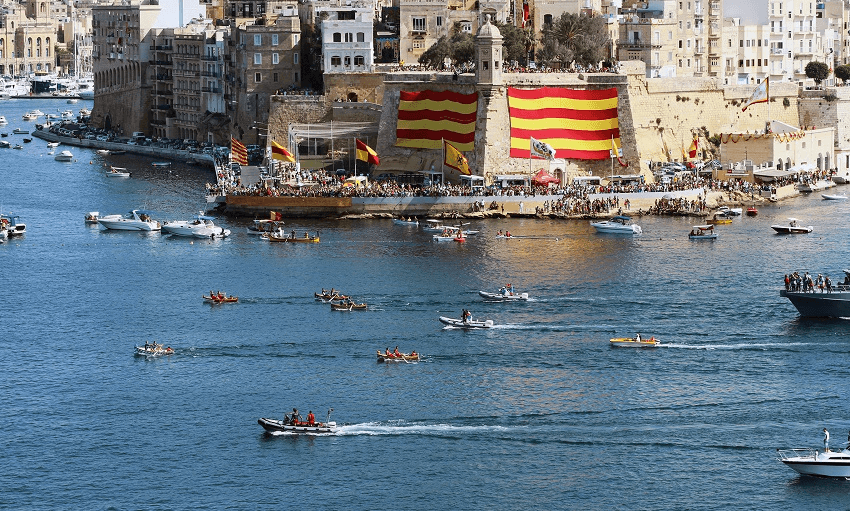

I have suggested before that our tourism industry leaders should fly out to Malta to seek its help in solving the problems of exponential tourism growth. It’s certainly a problem Malta has to deal with.

The Mediterranean archipelago’s rising standard of living and national wealth follows the implementation of growth and wealth creation strategies.

Its first strategy was to exploit its wonderful weather by providing tourist facilities for those who could afford to chase its sunshine and azure seas, the latter relatively clean because of its low population.

The second was to sell its excellent educational system conducted in the international language of English to the wealthy, ambitious Eastern Europeans who could afford to give their youngsters a boost into global careers.

Thirdly it began selling its languid lifestyle and generous social services to the extremely rich, supplying Maltese citizenship and a passport in exchange for 1 million euros and a commitment to buy a house in Malta or create employment in well paid jobs.

It also sells its highly educated and skilled work force in areas such as engineering, mechanics, medicine, dentistry and, more recently, software.

Malta’s biggest emphasis has been on tourism. A country which last month reached the population milestone of 500,000 now attracts three million tourists each year, a six-to-one ratio of tourists to locals.

Imagine New Zealand catering not for four million visitors per year but thirty million, six times our population. Imagine our need for hotels, motels, rental cars, roads, road barriers, international language signs, restaurants, adventure operators, ferries, sewerage and water systems, airport runways and customs officers.

How does Malta cope?

The truth is that Malta copes but with increasing discomfort. Many of its villages are frustrated by the constant development (last year was a record year for construction), the road building, the dust, the traffic jams, the car parking problems etc. The locals do not celebrate the success of the strategy as much as they did when there was an obvious need to create wealth and jobs.

All of its strategies have succeeded, leaving many wondering why yet more growth is desirable. The selling of education to Eastern Europeans remains controllable and attracts little criticism. Indeed, two new international educators have just signed a deal to come to Malta and pay the government handsome royalties for the licence to educate another five hundred foreign students at a site long abandoned. They will build the facility with local companies providing the construction services.

The selling of skills has worked brilliantly. Malta services aircraft for major airlines like Lufthansa, and is now a country highly regarded for its development of technology and software.

The risky strategy of attracting the world’s internet gambling providers has created highly paid jobs and lifted wages generally, enabling young people to develop lucrative careers and in the process lift the tax take.

The sale of passports too has been astonishingly successful. Last year nearly 2000 people of significant wealth each paid the €1 million price for citizenship and access to Malta’s social services and health system, the latter having short waiting lists. Two billion euros for Malta would be like twenty billion for New Zealand. Handy.

The countries providing the biggest number of new immigrants were, in order, Russia, Saudi Arabia and China. One in seven people living in Malta today was not born in Malta. The average for Europe is one in 14.

Russia and Saudi Arabia. Hmmm.

Last year’s €2 billion in passport revenue enabled Malta to reduce its debt from 51% of GDP to 45%, one if the lowest ratios in the world and barely a third of the debt level of its neighbour Italy. Malta’s success seems all the more spectacular because of the contrast with its neighbouring island, Sicily, just a 20-minute flight away. The southernmost Italian island has low living standards, effectively no social services and precious little support from the wealthier north of Italy.

Sicilians now eye Malta in much the same way out-of-luck New Zealanders used to line up Australia. They are excellent restaurateurs and there are now many Sicilian restaurants in Malta, whereas just 10 years ago such establishments were rare.

Sicily is, of course, noted for the informal groups who ‘supervise’ its society.

Russia, Saudi Arabia and Sicily. Hmmm.

The result of all these successful strategies is that Maltese salaries have doubled in less than a decade. Pensions are generous. Education, right through to tertiary level, is free, providing exams are passed. Pensions begin at 65, though for policemen they can begin after 25 years’ service.

There is no unemployment. Indeed, Malta is forced to import people from Eastern Europe, Italy, Greece, Turkey, even Venezuela, to service the tourists. Many speak no Maltese and very little English. Young Maltese people do not want the relatively low wages paid to waiters and hotel staff.

The talk of peak tourism is widely reported in the excellent daily paper, The Times of Malta, and dominates discussion in cafes and town squares. I called in on a club for the local brass band people, having discovered its Sky channels showed events like Wimbledon. At the club my table talked of little else but tourism.

New Zealand should be observing and listening.

Of course, the locals acknowledge the growth in incomes in a country so blessed by the weather gods. Good incomes make the midday siesta more affordable! Yet there is one more result of all this rapid change that now enters cafe dialogue.

In a country which for centuries has enjoyed the leadership of the Roman Catholic Church, Malta has always maintained values that separated it from countries that worship the dollar (or euro). It has never been a contender for lists of corrupt countries. But while its serious crime rates are a tiny fraction of its neighbour, Sicily, the combination of internet gambling, new immigrants from countries where corruption is rife, and politicians singularly focused on creating wealth may result in new challenges.

Malta’s Labour government is now attacked every day in the clearly independent, brave daily Times, to the extent that one wonders what defamation laws protect the public officers.

Having delivered jobs and higher wage packets, the prime minister Joe Muscat seems to have no energy left to answer simple media questions. As an example, he was pestered for months to explain the role in the public sector occupied by a man he has used almost as a personal envoy, meeting with war lords in Libya and elsewhere.

Muscat would answer that he knew the man worked in the public service but had no idea which of the thousands of roles he occupied. How could a busy prime minister be expected to know where every Tom, Dick and Sebastiano worked? Last week Muscat cracked. OK, alright, yes, the man is in my personal advisory team. OK? But I’m not telling what he does.

Muscat has grown Malta’s economy at a scarcely believable pace: no unemployment, doubling of average wages, increasing tourist numbers, construction everywhere, house prices and rentals rising. It is the fastest growing economy in Europe averaging 5% in recent years, whereas the likes of Germany and France average less than 1%. Malta’s population is also the fastest growing in Europe, though not from its albeit relatively healthy birth rate.

Yet the people seem unsure that all of these advances should continue at an unchecked pace.

Is exponential growth an opportunity or a threat? I expect you might get the same conversation in the cafes of Queenstown, Wanaka, Waiheke Island and Auckland’s North Shore.

Right sizing might soon become an election issue.

Chris Lee is a financial planner and principal of Chris Lee & Partners.