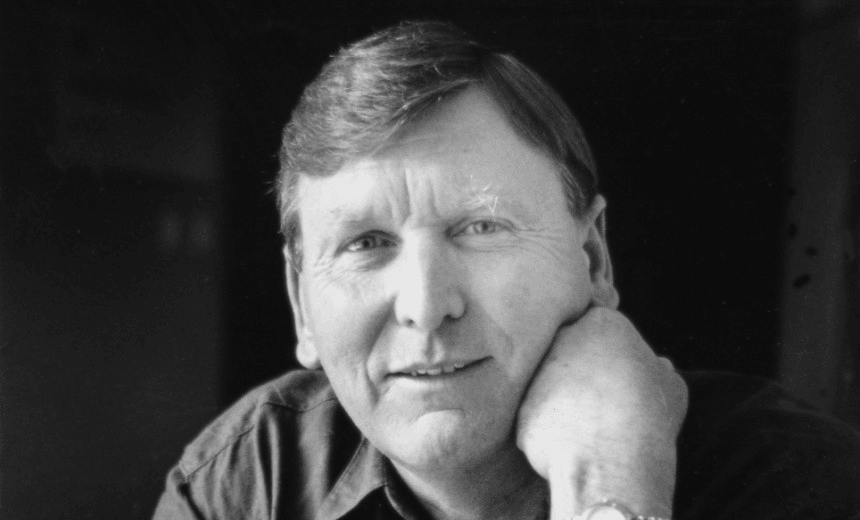

Sue Orr admires the latest work of the master: Owen Marshall’s new novel, Love As a Stranger.

I’ve always been wary of thrillers. I don’t like the way they so brashly presume they’re going to thrill me. That gets my goat, as my mum would say. Their ardent determination to surprise feels fated to self-sabotage.

From time to time I accidently agree to review a thriller. It’s always my own fault, I fail to read the fine print. Last time it was SJ Watson’s dreadful Second Life. I said terrible things about that book somewhere other than here. I thought it was a very good idea that the author had chosen to use his initials rather than his full name.

This time it’s Owen Marshall’s Love As a Stranger. Owen Marshall is not Owen Marshall’s real name, but you shouldn’t read anything into that. Marshall has written a real thriller. His (and his publisher’s) first smart move was not to describe it as such on the cover.

The novel thrilled me not because of its plot, which is a satisfying slow-simmer, but because its complex crafting upset my reading expectation. It’s a book of and about shadows; slippery people, slippery ideas. Most unsettling, in a very good way, is Marshall’s guileful, mysterious third-person narrator – a mere shadow of a shadow yet a strident, sometimes sexist, opinionated voice in his own right.

“People in love have a longing to tell others how they met, even if the circumstances are banal, or best supressed. It’s an expression of their wonder, and gratitude for having found each other. Sarah and Hartley met in the old Symonds Street cemetery, though neither had links with any of the residents there…”

Thus, in the opening lines of the story, this unknown narrator claims the right to speak, to judge. We may or may not wonder who this person is, as we settle into the story. But as the tale grips and progresses, the reader cannot ignore this Jiminy Cricket jumping from shoulder to shoulder of the three protagonists Sarah, Hartley and Robert. He balances precariously, watching and listening. He is charged with representing their consciences but he, too, has views to share. Sometimes it’s hard to tell which is which.

Love As a Stranger is set in Auckland. Sarah, 59, is living there temporarily with her husband Robert, who’s undergoing treatment for cancer. Standing by the grave of a young murdered woman, she meets Hartley, 58, a passer-by. They strike up a conversation and agree to a coffee date.

Coffee leads to friendship which leads to sex, or fucking, as our narrator regularly defines it. A fair bit of fucking ensues; too much, it transpires, for one of the lovers. Things start to get a bit thrilling.

The narrator’s choice of words, his manipulation of language and ideas here and elsewhere, slowly start to register as discordant. The gap between the type of people we are being invited to think Hartley and Sarah are, and their portrayal on the page, becomes increasingly wider, more disturbing.

This unknown narrator also happens to have strong opinions on women’s weight, their physiques, and he likes to mention them frequently. Amber, he notes, was a head taller and a cheek wider at the arse of her jeans… she had a lovely smile as women with plump faces often do. The narrator has views, too, on the moral and economic health of society.

There’s plenty of terrific description in this story – Hartley’s parents were a Jack Sprat couple without the benefits and in a dirty street, the wind flicked and tumbled tissues like wounded doves. Marshall’s reputation as a supreme wordsmith and master craftsman of style is showcased beautifully in this, his sixth novel. But Love As a Stranger ultimately challenges us to think hard about truth and passion. The novel’s pages feature the ever moving shadow of a man, and at first I presumed it was Hartley. By the end of the book, I wasn’t so sure. Marshall is forcing us to feel, for ourselves, the sensation of being unsure about things. He’s forcing us to think about who tells us stories and whether we should believe them. His narrator’s judgements remind us that we each have biases and obsessions, and that those traits cannot help but colour our views of others.

He’s challenging us, too, about how we account for ourselves and our weaknesses. Sarah and Hartley don’t know each other at all; by the end of the story they don’t even know themselves. When love is not madness, it is not love, the book’s epigraph says. It’s a challenging notion, perfect for this novel.

Love As a Stranger (Penguin Random House, $38) by Owen Marshall is available at Unity Books.