Just how worried should NZ homo sapiens be about talk around a surge in shark numbers in our shore, and the unexpected visitors to Oriental Bay. Alice Webb-Liddall talks to Riley Elliott.

It’s a scorcher of a summer, and as reliable as sun burn and ice creams come the shark headlines. The Jaws effect, even 43 years after the film’s release, has some too scared to wade beyond their ankles for fear that a great white might leap from the shallows at Takapuna Beach. A floating branch or the shadow of an arm on the seafloor can make hearts skip a beat.

Most recently, schools of rig sharks have been spotted within metre of the sand at Oriental Bay in central Wellington, prompting many beachgoers who would usually be wading or swimming to huddle on the beach, prompting discussion around perceived increases in shark populations around New Zealand, and fears around threats to safety.

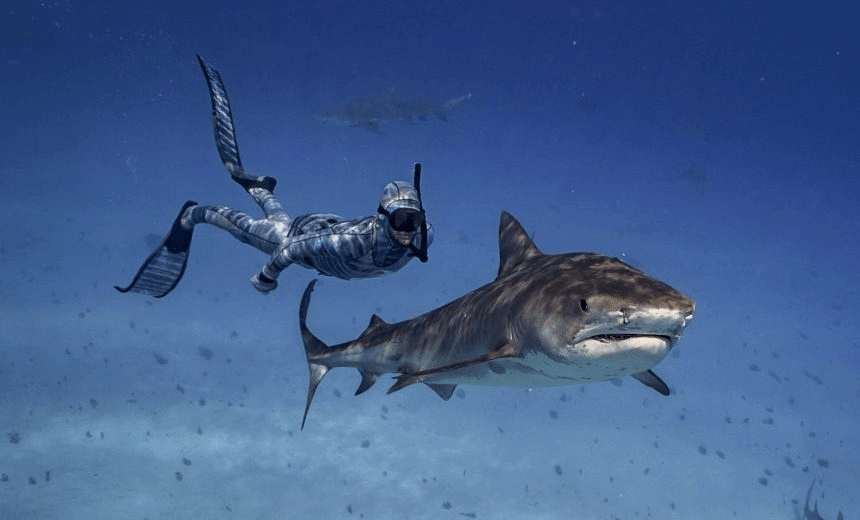

With waters up to six degrees above the average in the Tasman Sea for this time of year, are more sharks circling our shores? Should we be worried about the Oriental Bay visitors? And if we were to come nose to nose with a big finned dish, what should we do? We put these questions and more to Riley Elliott. Also known as “Shark Man”, Elliott is a marine scientist who has made friends with the much feared fish.

The Spinoff: Why are so many sharks being sighted this summer in New Zealand waters?

Riley Elliott: To put it simply it’s a perception thing. This time every year more and more kiwis are on the water than usual, so it makes sense to see more and more sharks. Because quite simply there are more eyes on the water. Scientifically there is actually no evidence whatsoever to support the claim that there are actually more sharks in the water – in fact, I suggest the contrary, whereby shark finning over the last 30 years has vastly reduced the global population of sharks. Take away the fact that people perceive these things over summer much more often than usual, your smartphones, your cameras, and it sells a whole bunch of newspapers when you put a shark on the cover. It’s kinda like when you see a white Mini, you start seeing a whole bunch of other white minis, it’s that kind of pseudo-effect of when you’re looking for it or thinking about it, plus there are more eyes in the water, people are going to see more and feel like there’s more. But factually, there is nothing to suggest that there are actually more sharks in our waters today than there were this time last year or the year before.

What kind of sharks do come in to New Zealand waters?

We do have an increased occupancy in New Zealand at this time of year of particular species, mainly the pelagic migratory species. Put simply, that’s the sharks that live out in the deep blue; your mako sharks, and your blue sharks, and your hammerheads. Those sharks regularly migrate with the East Australian Current that pushes down from Australia down to us and brings our warm summer water. They migrate with that water because it has smaller fish in it, then tuna, then marlin, and up the chain to sharks. The reason for that is when this warmer water migrates down into our cooler water it creates a lot of productivity from phytoplankton up to plankton and all the way up that food chain. So it’s not unusual when we go out fishing this time of year to have the odd mako come around the boat and harass your boat engine or try to nick a few of the fish that you’re pulling up, or the lazy blue sharks kinda hanging around. The hammerheads are much more shy and will generally avoid you. The main shark we see along the coastline is the bronze whaler, and that’s because it’s a coastal species that lives in New Zealand waters year-round, and we most often see it by no coincidence, on all of the very popular summer beaches because there’s more eyes on the water and the sharks like to sunbathe in the white water because the waves do the breathing for them.

In the case of places like Oriental Bay in Wellington where there seem to be quite a few sharks at the moment, should beachgoers be worried?

Well, this is an apex predator that has teeth. Luckily it’s evolved over 500 years to eat specifically the small little fish. The ocean is where sharks live and we should respect the wild environment any time we venture into it. That respect comes from an understanding of why it lives there and the behaviour of those animals. I say to people; “you don’t climb Mount Everest without understanding how to, nor should we swim in the ocean without understanding it”. Things like rips for example, are far more dangerous, statistically, than sharks are. Places like Oriental Bay, people say ‘oh, there’s a few sharks floating around there’, but it’s a very unlikely shark habitat: there’s a lot of boating activity, to be honest the water’s not that clean because of urban runoff, and there’s a lot of people.

Sharks, generally, are very conscious animals, they prefer premium habitats, clean water and great fish life and those would be generally away from where people would go. When we remove our perception as an average punter on holiday, and you look at it scientifically, sharks live far beyond where people generally roam, but it is important that when we do go into the wild environment, that we respect sharks and we understand what they do for the environment and how to respond if we do see one.

What is the correct response if you see a shark when you’re swimming?

The first rule with any predator is eye contact. Now if you’re swimming and your head’s above the water, obviously that’s harder to do, but if you’re snorkeling, scuba diving, spearfishing, then maintaining eye contact with that animal will keep it at distance and keep it aware that you’re aware of its presence, and it removes any ambush device that it has. You can relate it to a naughty dog in the corner, if you look at it and point at it, it’s going to stay there but as soon as you walk away it’s going to try to nip your ankles, take the food, or whatever mischief it was going to do.

The second rule is clear water. You need to have clear water so the animals and yourself can see and there’s no mistaken identity and there’s no thinking that you’re something else.

The last thing is just being aware of the water conditions outside of that visibility, meaning don’t go swimming where people are filleting fish, don’t go swimming where seals or fish or birds are eating, don’t overlap your location with where these predators would be hunting in their natural environment. It basically comes down to respect, understanding, and if you see a shark, enjoy it because they’re rare animals and they’re all-too-quickly gonna run away from you because they’ve evolved and they’re smart and humans are generally dangers to them.

NIWA forecasts say temperatures in the ocean are up around 6 degrees celsius since this time last year. Could this temperature increase have brought any increase in numbers of sharks?

Yeah, there is a huge possibility of that. A lot of the work I’ve done is about locating pelagic migratory sharks to see where they go and when they go, and correlate the environmental variable with those movements so we can try to predict how migration patterns might change with things like warming waters. This summer is far hotter than most of us can remember, as is the water condition.

Over the last few years I’ve seen, with these warming waters, they’ve changed the distribution of the blue sharks that I studied because the hammerheads will predate on the blue sharks. So you do get this shift in what species inhabit certain environments when the variables change. I don’t think we’re at any risk of having tiger-sharks turning up in robust numbers, or bull sharks, but these animals do move with certain bodies of water, and as the climate change and temperature changes shift how these bodies of water move, it is highly possible that species will differ and some species will be pushed out of their usual environment.

So you’re saying the increase in shark sightings this year is due to an increase in beachgoers this summer?

This is the time of year when everyone goes into the water, what’s on your mind when you go into the water? Well a large proportion of people think ‘sharks’, and that’s because their only education on sharks has been ‘Jaws’. It’s this habituation that you should be afraid of the ocean and sharks, and if that’s on your mind, everyone’s looking for them, everyone’s thinking about it, and you put all these people who aren’t usually on the water out there, and there’s far more people to see these animals. I say you shouldn’t be surprised to see a shark in the water. It is where they live. Unfortunately emotion gets involved in these things. It does make good stories because people are afraid of them and they want to know about that fear, but at the end of the day, there is no scientific evidence to suggest an increase in shark numbers, however we do get migratory species coming to New Zealand at this time of year with these warm water currents. These animals generally live far beyond where we go out and swim in places like Oriental Bay and Takapuna or anywhere of general use to the public.

Riley Elliott is the author of Shark Man: One Kiwi Man’s Mission to Save Our Most Feared and Misunderstood Predator

The Spinoff’s science content is made possible thanks to the support of The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a national institute devoted to scientific research.