Both pigs and humans alike should rejoice over the High Court’s ruling on farrowing crates, writes University of Otago law lecturer Marcelo Rodriguez Ferrere.

If you know anything about pigs, it’ll likely be that despite their slovenly and biblically-dubious reputation, actually, they’re quite clever creatures. As smart as dogs! As smart as chimpanzees! At the very least, pigs are “intelligent, aware, emotionally and socially sophisticated beings.” However, “intelligent” and “sophisticated” aren’t adjectives you’d use to describe New Zealand’s animal welfare system after a damning ruling on Friday by the High Court.

In its judgment, the High Court ruled “farrowing crates” and “mating stalls” for pigs as unlawful. That’s the simple takeaway, and a powerful one it is. But the way Justice Helen Cull reached her decision is revealing of a complex, almost Byzantine system we use to regulate animal welfare in this country. That revelation means the judgment wasn’t simply a victory for pigs and their human advocates – New Zealand Animal Law Association and SAFE – who brought the case to court. It was a victory for all animals, since it exposed some pretty major flaws in our animal welfare system, and will hopefully spur the case for wider reform.

The starting point to any analysis of that system is the Animal Welfare Act 1999. This legislation enshrines the five freedoms for animals which at the time of enactment 20 years ago was a world first. Those freedoms include access to proper and sufficient food, water and shelter. Critically, it also includes the “opportunity to display normal patterns of behaviour”. Anyone who owns or is in charge of animal has a statutory obligation to provide for those freedoms.

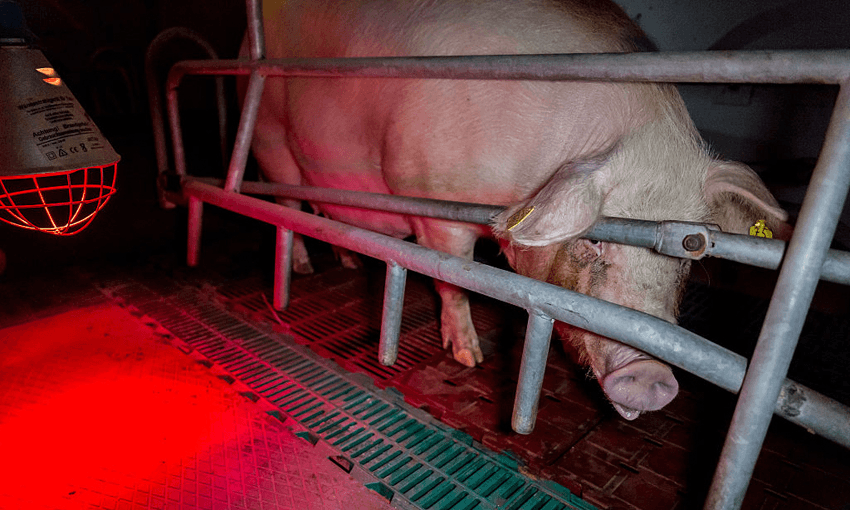

About half of all pig farms in New Zealand use farrowing crates and mating stalls. While there are some important differences between them, to the untrained eye they are essentially similar since they serve the same purpose: to prevent the sow from turning around. Mating stalls are used to make mating (or, more likely, artificial insemination) an easier process (for the inseminator). Farrowing crates are used when sows are weaning their piglets, the theory being that if the sow can’t turn around, it minimises the risk that she’ll accidentally crush one of her piglets.

You don’t need to be a pig to see the disjunct here. A pig being able to turn around is surely “a natural pattern of behaviour”. How, then, if the Animal Welfare Act guarantees pigs the “opportunity to display normal patterns of behaviour”, was it ever possible to use mating stalls and farrowing crates? The answer lies in the next tier of our animal welfare system. The Animal Welfare Act allows for the creation of both “Codes of Welfare” and regulations that specify minimum standards for particular animals or industries. There’s a Code of Welfare for everything from commercial slaughter to Llamas and Alpacas. There’s even one for companion cats. If you have a cat and haven’t read that code, you now know why your cat has forever looked unimpressed with you.

Until 2015, Codes of Welfare could specify minimum standards that would otherwise fall below the general requirements of the Animal Welfare Act and those five freedoms. Farrowing crates and mating stalls originally fell under this loophole. However, a big amendment to the Animal Welfare Act in that year meant that thereafter, any standard that fell below would need to be specifically allowed for in regulations, with a view to being phased out eventually.

A body called the National Animal Welfare Advisory Council (NAWAC) is responsible for overseeing these codes and the regulation-making process. The Court found that when it was creating Codes of Welfare for pigs in 2005 and 2010, NAWAC consistently wanted to see both farrowing crates and mating stalls eventually phased out, since it saw them as contrary to the general obligations in the Animal Welfare Act. Yet in 2016, it changed its tune. In a complete change of position, it now viewed farrowing crates and mating stalls as consistent with the act, without the need to be phased out. Bizarrely, the basis for the change in position was because there hadn’t been any change in the science to provide viable alternatives to the crates and stalls. That’s a little like saying, “well, science still hasn’t worked out a way to drink and drive safely at the same time, so instead, we’re just gonna say it’s pretty legal”.

Here’s the thing with regulations and codes of welfare though. They’re what we in the biz call “subordinate”, “secondary” or “delegated” legislation – parliament delegates the power to the government to make such legislation, but it’s always subordinate to primary legislation enacted by parliament, like the Animal Welfare Act. That means when it’s inconsistent with primary legislation, the court can strike it down as invalid and unlawful. That’s what Justice Cull did here: since the relevant Code of Welfare and the regulations allowed for farrowing crates and mating stalls without any indication of when they’d be phased out, it undermined parliament’s intention that non-compliant practices such as this would and should be phased out. Since it undermined parliament’s intention, it was “ultra vires” or beyond the power given by parliament to the government, and thus unlawful. Further, Justice Cull directed the minister responsible to consider enacting new regulations that will phase out the use of mating stalls and farrowing crates.

While this might seem utterly complicated, here’s the key point: if a status quo practice under the Animal Welfare Act is non-compliant, “science hasn’t found an alternative” is no excuse to allow the status quo to continue in perpetuity. Parliament and New Zealanders have made their voices clear: we want higher standards of animal welfare, and if that means abandoning non-compliant practices, so be it. For the first time in New Zealand history, a couple of pretty courageous NGOs took that sentiment to court and won. And this theory won’t just be confined to pigs: it’ll be applicable to our whole system, which is why it’s so important. NAWAC, and the government will have to take a long hard look at how it regulates animal welfare if it wants to avoid more cases like these in the future.

New Zealand Pork, the statutory industry board that works to support New Zealand’s commercial pig farmers, is obviously pretty annoyed about this decision, with the reaction ranging from “won’t someone please think about the piglets” to “if we have to improve our systems, that’s going to make New Zealand pork pretty expensive!” Don’t believe it. The science suggests farrowing crates only save approximately 0.4 piglets on average. That’s not zero, but it’s at the completely disproportionate cost of the sow not being able to turn around. Plus, there are plenty of farms in New Zealand that don’t use farrowing crates, including and especially those pioneering free-range pig farms. And as for the threat of cheap and cruel overseas pork flooding the New Zealand market, well, you can demand the government get its act together on country-of-origin labelling, and then, like NZALA, SAFE and the High Court, you can think about the pigs next time you’re at the supermarket.