A game where two dudes break out of prison isn’t groundbreaking, but A Way Out still tries to play with expectations. But is it successful? Sam Brooks reviews.

About a third of the way into A Way Out’s five hours there’s a classic co-op game moment. You and your heroes have to navigate your way up two opposing walls by going back to back and slowly climbing it. If one of you fails, you fall down a little, but if you sync up entirely you can make your way up the gap quickly. It might take a while, depending on who you’re playing with, but once you finally get in sync it’s a hugely satisfying moment.

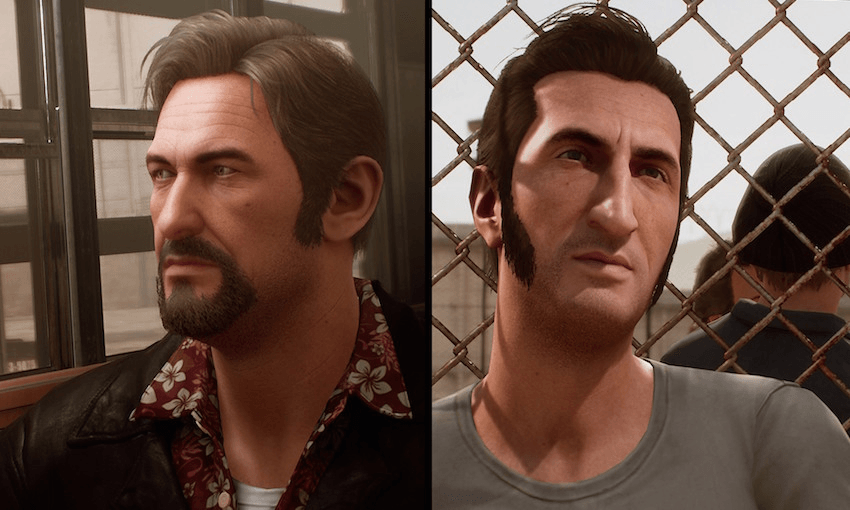

There are moments like this scattered throughout A Way Out, the new co-op experience from Hazelight Studios, which follows two criminals, Leo and Vincent, as they break their way out of prison and get revenge on a man who has wronged them both. Unlike many recent co-op games, you largely play this one split-screen (but you can play it online, if you are so inclined) with each player taking control of one character.

I played this with my best friend, someone who I play games with semi-regularly. As is usual when we play games, we had a bit to drink, reclined as far back as was possible and waited to be unimpressed by the game. That kind of approach to something, be it a game, a TV show or a movie, sets you up for a particular experience.

But for the first part at least, A Way Out had us sitting up and engrossed. A prison break, which is where the first act takes place, is a savvy setting for this kind of game. One character distracts the guards while another one steals a tool they need to get through. It’s a challenge that relies on co-operation, which the narrative gradually fosters not only between the characters, but the players themselves. The ongoing dialogue we had with each other as players was even more engrossing than that between the characters we were playing.

Which brings us to a fundamental, and hugely limiting, aspect of A Way Out: the characters, and by proxy, the narrative. Leo and Vincent are cliches, and it seems they’re intended to be so. Leo is the loud and aggressive one who resorts to violence to resolve problems, whereas Vincent is more calm and rational. Their familiar buddy vibe isn’t particularly inventive or engaging, and the narrative doesn’t take them anywhere that hasn’t been covered by this genre before. You will not be surprised to learn that these strangers become friends through co-operation

It’s a whole lot of men being men. And if that’s your thing, that’s absolutely fine. I know a couple of handfuls of people who want nothing more than to play as dudes being dudes, and don’t necessarily need to be engrossed by the dialogue or the narrative to have a fun or meaningful video game experience.

To its credit, A Way Out largely does the fun part. The game features a huge variety of challenges – there’s the pixel point-and-click part, the stealth part, the driving part, and even the run-and-gun part. Mostly, it’s like playing through an interactive movie. In this it’s very successful, shifting seamlessly through the game mechanics while always feeling like a movie watching experience. The game even includes cinematic moments that would be impossible in actual cinema but which this medium makes possible – the shifts between characters during one particular one-foot chase scene come to mind.

And then the game drops the ball, and in a way that brings to mind not the tense ’70s thrillers that the game is clearly inspired by, but a trashy ’90s action film. A Way Out starts off at The Great Escape and ends up at Bad Boys. The last act of the film especially feels like a misguided attempt to elbow into Uncharted territory, without the robust gunplay mechanics that make that series such a joy to play. What has been an engaging co-operative experience up until that point instead becomes yet another cover-shooter, and it’s disappointing.

If you do not want to be spoiled about the ending of A Way Out or do not particularly care, skip down a few paragraphs to the end of this review.

The moment A Way Out especially fumbles – but which could have been a truly defining moment in this genre – is the last set-piece. In one of the only surprises in the game, Vincent ends up being pitted against Leo and we don’t just have to see this fight play out – we have to fight it. And it’s not a one-and-done cutscene battle, it’s a proper shoot-out.

It’s a brilliant move. The game doesn’t only make two characters who have spent the game together have an emotional shootout, it makes two players who have been co-operating with each other throughout the game do the same. These are players who have helped each other through both frustrating moments (god knows we spent way longer on some of the stealth sections than necessary) and hugely satisfying ones (the eventual prison break is adrenaline building if nothing else). And now they have to throw that all aside and shoot each other.

It’s a meta-dynamic that c0-op games rarely play upon, and it’s a surprisingly complex one for a game that has so far been devoid of emotional complexity (you don’t really need to ask how this game treats women, but you can imagine that it is not particularly imaginatively).

But… it doesn’t quite get there, because of reasons that are emblematic of A Way Out‘s problems. Mechanically, this should be an evenly matched fight, but it’s really not. I am much less talented at shooting games than my friend and the moment the game shifted to this final shootout, I knew there was almost no chance that I would win. It became less of a ‘oh shit I need to kill Leo’ and more ‘oh well I can’t win now but I’ll do my best’ – which could totally work if the game set it up like that, but it doesn’t. The game suggests that either character could win but in reality, you’re probably going to have two players with different gaming skills. And if those skills don’t include shooting, then that player is out of luck.

Another problem: this moment doesn’t work emotionally, because the game doesn’t engage us enough in the story of these characters. Vincent’s betrayal makes sense, but we’re not angry at him for it, because we understand it. The player who is playing Leo can’t be as angry as Leo is, because he’s seen Vincent’s story and is unlikely to be as emotionally invested in killing Vincent as Leo is. So while you’ve got the ‘oh shit!’ moment, you don’t have the emotional follow-through and a moment that is emotionally charged for the characters doesn’t quite land for the players.

The generic nature of both of these characters, and their specific wife-and-child-still-waiting-for-me problems, doesn’t exactly help either. Leo and Vincent have very similar issues with their female partners (who are, of course, given enough depth to show that they’re romantic partners and not a single centimetre more), which seems less like a demonstration of common ground between the two and more like simply lazy writing. Given the cliches throughout the game – and the bizarre ‘Central American drug lord’ detour it takes in the third act – I’m inclined to believe it’s the latter.

The spoilers end here! So you can start reading again, or continue reading, if you don’t care about spoilers.

A Way Out feels like an important step in the right direction for both co-op games and games that desperately want to be cinema. It tries to give emotional depth to the meta-game in a way that is lacking in many mainstream games, and its wealth of gaming mechanics is a rarity in the cinematic game genre. However it stumbles by its adherance to well-trodden narrative tropes and character beats, and no amount of inventive or progressive attitudes to gaming can really fix that.

This post, like all our gaming content, comes to your peepers only with the support of Bigpipe Broadband.