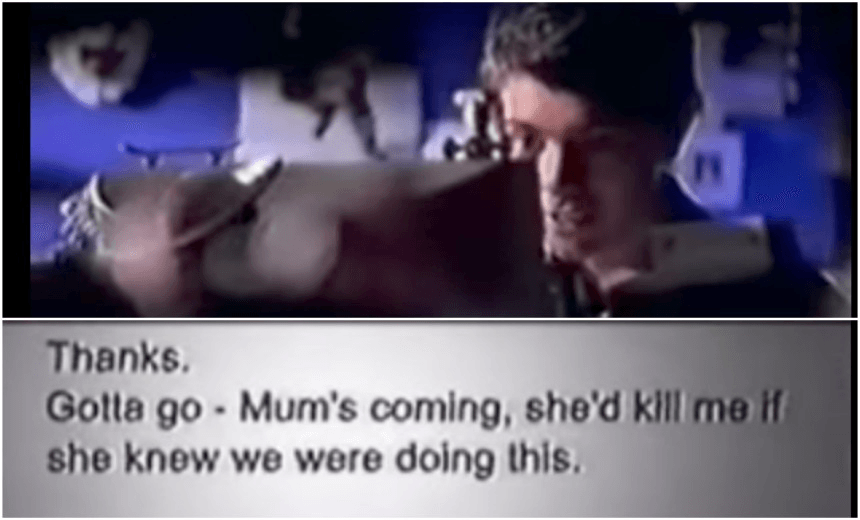

‘You’ve seen what’s on his screen – imagine what’s on his mind’ warned the voiceover in a 1999 PSA about online paedophiles. The ad’s star Joseph Nunweek remembers its filming, and reflects on how our perception of internet safety has changed in the years since.

Fame is fleeting, but it changes you. My television acting career, which lasted approximately one day and paid $0.00, was no different. Before the gig, I was brimming with excitement, all daydreams of going on Shorty and elliptical and enigmatic remarks to my classmates to pay close attention to the ad-breaks in a couple of months. After the gig, I didn’t tell a soul, terrified that someone might see it and identify me.

Eighteen years on, I don’t feel quite as bad about having been the PSA poster child for Australasian internet safety. The re-discovery came the other day at work when I was yarning across the office about ICQ and MSN nostalgia. I searched YouTube on a whim, and like the rest of our cultural detritus, I’m there. My name is ‘Tim’, I’m 13 again and I’m typing into a tiny chat box to what I mistakenly believe is the girl of my dreams. Though its narrative of online catfishing seems goofy and dated, it still unleashed a volley of weird personal and cultural memory for me.

The ad was commissioned for ECPAT (End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes) – I would have no idea what the production company was – and filmed in star-studded Eden Terrace, Auckland. ECPAT, by my reckoning, chiefly devote themselves to important international work against child slavery and exploitation these days – for better or worse, a browse of their YouTube uploads shows they’ve never discovered a New Me.

And what a discovery I was! Fresh from my turn as Balthasar (the three-line servant boy) in Mount Roskill Grammar School’s production of Romeo & Juliet, I was offered the part when a former student got in touch with our drama department. This felt like a huge validation at the time of my thespian abilities. The reality is more banal. I had – still have, maybe – a simpering and sad smile matched with watery blue eyes which made me look like I was perpetually on the cusp of tears, and it made me a young victim straight out of Central Casting.

I was whisked to their production studios, which felt like the absolute cutting-edge of cool – a free Coke, lots of smooth unpainted concrete surfaces, and Moby playing at deafening, melancholy volumes. I signed a contract which stated that the role was unpaid, but that I would be due some payment if the PSA ever played on an airline (this seems absurd, I know, but I remember that part very strongly).

You also have to remember that to my mind, this was good exposure. The ad would be the debut that set of the bidding war for my time and talent. I also enjoyed a humongous and free catered breakfast (danishes, donuts!) that would not have been entertained in the Nunweek home.

I spent the next five hours acting my wee heart out (smiling, simpering, yearning) in front of a keyboard. The stage methods had served me well – lay television viewers will be amazed from my performance to learn that the monitor I used didn’t even work, and that my incredibly realistic performance is a Brechtian post-modern feat – in each take, I pretended to be chatting online to a middle-aged man pretending to be a tweenage girl.

Acting under lights and the pressure of the camera is hot work – Kiwi men of a certain vintage will remember the way fin-de-siecle hair product turned to pâté and greased down their forehead, and their hair would sag over the course of the day. I put up with this, picturing how dramatic and emotional the ad would look – a fashionable young boy in love, quick cuts, a cool soundtrack, a rendezvous betrayed. I had Baz Luhrmann’s R&J on the brain still – and after all, these people listened to Moby.

There are many things, then and now, that are chastening about the final product. The “teenage boy’s bedroom” I’m in looks like it was designed by the maker of Dilbert – I’m basically in a tiny office cubicle. The silence and pace of the majority of the ad is unearthly – by the standards of advertising geared to children, it’s a 10-hour video installation. And the chat messages themselves are all immaculately spelt and punctuated. This might be expected from ‘Debbie’, who isn’t actually a teenage girl. But I was actually meant to be a young person, and I’ve written legal submissions less stilted than this.

You can’t deny the power and horror of that ending though. All the panache missing from most of the ad is unleashed here, as ‘Debbie’ is revealed in his hairy armed, smoking splendor. As he stubs out his filthy dart, the definitive voice-over of NZ public awareness TV speaks “The internet has become the hunting ground of the paedophile. You’ve seen what’s on his screen – imagine what’s on his mind.” Astonishingly, this cultural moment preceded the airing of Brass Eye’s totemic “Paedogeddon” curtain call by a year.

Worst of all – I was barely in it, for all of my sweaty hours of labour. And I looked like a little nerd. No calls from the talent scouts ensued, and I remained very, very circumspect about the ad. When a couple of kids at school did ask if it was me, I demurred. Absent looking cool or becoming famous, all I had was an showreel where I couldn’t talk to girls (already true) and wound up meeting a kiddy-fiddler.

The simpering and teary look was great for the gig, but not so much for school life. Effeminate, un-coordinated and verbose at the outset of my teens, I had entered the worst gauntlet of childhood bullying I would ever experience somewhere between the ad’s filming and its release. The PSA became a semi-secret stash of ammunition for my opponents, and I wasn’t about to broadcast its location.

My parallel experience at school really points to how the ad is an artifact of a different time. As Chris Morris identified, stranger danger was at an absolute fever pitch circa 1999-2001, and the media presentations were all tone-deaf. Child abuse was solely the preserve of faceless, hairy perverts – never someone charming, never someone in your community.

But the real pitfalls of the new century revealed themselves later. My early internet was a completely decentralised – one of Napster chatrooms, message boards and NewGrounds Flash animations. The bullying took place offline, and there was a secure partition between the two. I can’t imagine what it would look like today – your tormentors being on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, groups and message blasts you can’t switch off or opt out of.

Even the process of being exposed, traumatised and exploited online has been streamlined and centralised. Look at David Farrier’s terrifying and prescient piece last year on microphilia and pain fetish material being produced by unwitting children and solicited by adults. Or the NYT’s recent story on videos slipping onto YouTube Kids that involve violent and sexualized parodies, and even actual depictions of child abuse. A diffuse past of opportunistic and inept offenders has given way to a present where the automation and algorithims of one of the most valuable companies in the world enable this content and its dissemination. My ad seems quaint in comparison, like a museum piece.

That goes for a lot of ads, though – what probably mattered for ECPAT is whether it worked at the time. When I showed the ad to my flatmate Rachel, she had immediate flashbacks. A child of online chatrooms from her tweens onward, she said she saw it after school when it originally aired. “It was completely terrifying, especially the end.”

Did it give her pause for thought, I asked? “Would it help for the article if I said it had? Sorry, it didn’t. I went straight back to the computer.”