Fonterra has over 80 employees paid more than $500,000 a year. But are so many exorbitant salaries warranted for New Zealand’s farming cooperative? Jenny Ruth of BusinessDesk doesn’t think so.

In Australia, Macquarie Group is known as the millionaires’ factory because of all the lucrative deals it does that turn so many of its executives into millionaires.

New Zealand has its own version but, far from possessing the huge trail of successful deals Macquarie has pulled off, ours is a sorry tale of bloated pay packets, unwise investments and appalling financial results.

Because although Fonterra has failed in its mission to move the NZ dairy industry up the value chain, you wouldn’t guess that from examining the ranks of its best-paid executives and how they’ve grown over the years.

There has been some belated recognition of this since the departure of former chief executive Theo Spierings in 2018. Between 2018 and 2020, the dairy giant has pared back executive pay for those earning more than $500,000 a year by more than $37 million a year.

But executives in this category still cost the company between $64m and $65m in 2020. Companies are required to report the salaries of those earning more than $100,000 in $10,000 bands, hence the range.

Less pay

Spierings’ departure alone meant savings of about $6m because Spierings was paid more than $8m in 2018 while his successor, Miles Hurrell, was paid a little more than $2m in 2020. Hurrell wasn’t the top earner in 2020; another staffer who left during that year was paid between $2.3m and $2.4m.

Spierings also pocketed another $4.6m on his way out the door.

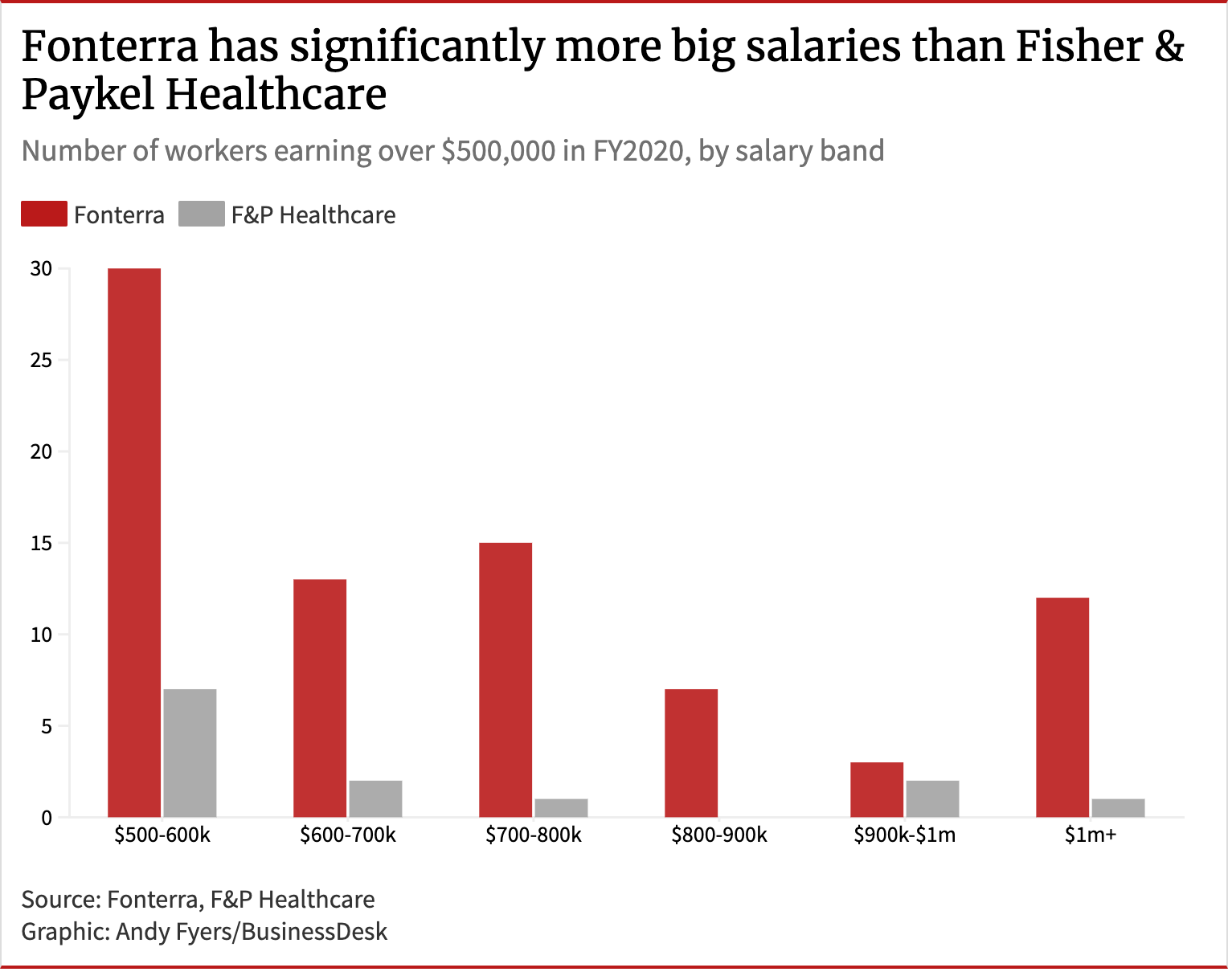

By way of comparison, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is the most valuable company listed on NZX with a market capitalisation of $18.87 billion last Thursday. Fonterra’s market cap is $6.52b, including the Fonterra Shareholders’ Fund.

Fisher & Paykel’s wage bill for those earning more than $500,000 in 2020 was between $9.3m and $9.4m.

In other words, in 2020, Fonterra was still paying its senior ranks nearly seven times the amount Fisher & Paykel paid its senior ranks that year.

Are we seeing Fonterra delivering seven times Fisher & Paykel’s returns?

Fonterra’s normalised per-share earnings peaked at 60c in 2010. They had fallen to 24c in 2020.

Compare that with Fisher & Paykel’s 2010 per-share earnings of 13.9c and 2020 earnings of 50c, near 3.6-fold growth.

Ironically, given Fonterra’s mission is supposed to be moving New Zealand’s milk up the value chain, its return on capital including from its brands, as well as capital and equity-accounted investments, was 6.7% in 2020 – less than its return on capital excluding those items at 7.3%.

Bad investments

One reason for the difference is the number of Fonterra’s investments that have gone bad. These include the 18.8% stake it bought for $755m in Beingmate, with more than 60% of that written off so far, and the more than $1 billion invested in China Farms, which it sold for $552m in April this year.

By contrast, Fisher & Paykel’s 2020 annual report showed its return on assets was 28.1% that year.

Fonterra’s staffing top-heaviness has worsened as time wears on.

Its first annual report in 2002 showed it had 974 people earning more than $100,000 a year, 46 earning more than $500,000 and nine of them earning more than $1m.

Collectively, these staffers cost the company between $191m and $201.7m.

By 2010, Fonterra had 2,785 people earning more than $100,000 a year, 78 earning more than $500,000 and 19 earning more than $1m.

The payroll for these high earners in 2010 totalled between $476.3m and $504.1m, nearly 2.5 times the 2002 cost.

Then in 2018, when the wage bill for high earners peaked, there were 5,994 people earning more than $100,000 a year, 107 of them earning more than $500,000 and 24 earning more than $1m.

More centurions

But after the culling of the very senior ranks, by 2020, it had even more people earning more than $100,000 a year at 6,354 than in 2018, with 81 earning more than $500,000 and 13 earning more than $1m.

While Fonterra has cut the expense of its ultra-high earners, the payroll for those who earned between $100,000 and $500,000 went up by somewhere between $8m and $12.2m between 2018 and 2020.

Whatever the merits of the proposals to change Fonterra’s capital structure, none of them even pretend to deal with its bloated executive ranks.

The apparent overriding aim of Fonterra’s owners, the farmers who supply it with milk, is to retain ownership in their hands.

But it’s obvious that what Fonterra needs is a strong dose of proper corporate governance and a much sharper scythe taken to its executive ranks. A commodity processor, which is what Fonterra really is, shouldn’t need anywhere near so many highly-paid staff.

But will it ever get such action while its shareholder base remains so dispersed?

The 2020 annual report showed it had 9,429 shareholders at July 31 and, outside of the 6.5% held by the manager of the Fonterra Shareholders Fund, the largest single holding was 0.06%.

Beholden to shareholders

Fisher & Paykel has what one would normally call a widely-held share register.

But its largest shareholder, American financial services company Capital Group, owns 6.4%, another US fund manager, BlackRock, owns 5% and yet another Yankee money manager, Vanguard, owns 5.25%.

All up, Fisher & Paykel had 24,551 shareholders at May 29, 2020, and you’d presume most of them would be New Zealanders since the company remains listed on NZX.

Would Fonterra have such bloated executive ranks if it had to answer to a few institutional shareholders?

How much better off would Fonterra’s farmers be if it did? To put it another way, what price are Fonterra’s farmers paying for retaining nominal full ownership of the cooperative?

The fundamental mismatch between what’s best for those farmers, at least in the short-term, and what’s best for Fonterra won’t be addressed by any tinkering with the capital structure either.

Farmers obviously want the highest possible price for their milk. As long as that’s their overriding aim their fortunes will always be tied to commodity prices.

But a milk processor such as Fonterra wants to pay as little as possible for its raw materials: those farmers’ milk.

There ought to be a better way forward for New Zealand’s dairy industry than allowing the Fonterra fiasco to continue.

This article originally appeared on BusinessDesk. Their team publishes quality independent news, analysis and commentary on business, the economy and politics every day. Find out more.