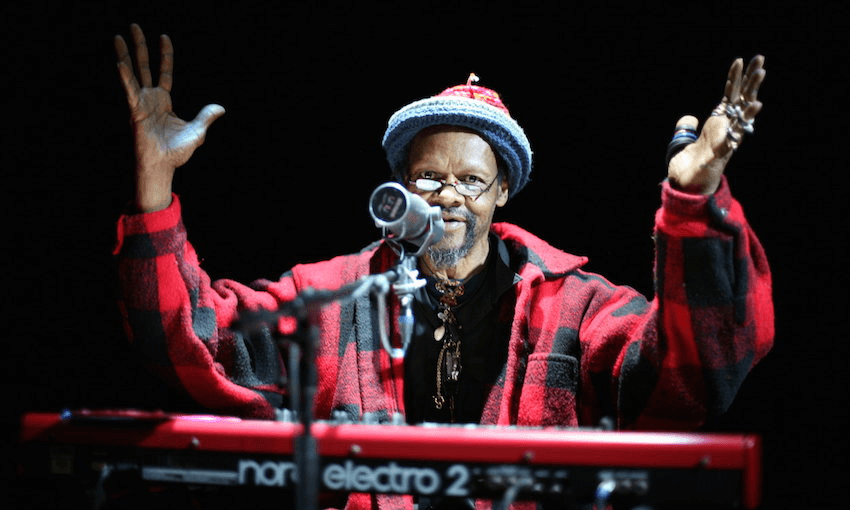

Tom Rodwell interviews the musician and artist Lonnie Holley, who this week brings to New Zealand his unbowed truths from an ethereal and gritty underground.

There is a creative archaeology, that tells a story gathered from society’s discarded debris. Lonnie Holley’s remarkable art and music embody this technique. With just the right kind of sleight of hand, such stories can even rewrite the storyteller.

Bulging everywhere with scavenged materials, broken and decayed, Holley’s studio in Atlanta is a place of reinvention, junk on its way to the gallery. A collection of an old lady’s improvised bedside weapons: golf clubs and baseball bats. Broken headstones, shattered musical instruments, a tree root interwoven between rocking chairs, a voting booth with a built-in pistol. His carvings are from industrial waste sandstone, his sculptures are from found objects, rubble from the side of the road, even the melted remains of a house-fire that claimed a neighbour’s child.

The latter work provides the title for the sprawling tone-poem ‘Fifth Child Burning’ on his first record – 14 minutes of chattering synth and vocals, traumatised and darkly comic.

“Each little object has a story to tell, and that’s what my work is doing, telling all the stories that had been either rejected or thrown away,” Holley explains. “You see, I think everything plays a part, a very important part. And it’s very, very rare – but this rarity should be understood.”

He works coloured rope into a bundle of hair. Once weaved into a woman’s scalp, the hair has been transformed by rain and wind into a tattered net, strewn with leaves and soil. Outside is Disaster Tree, bare branches clutching remnants of clothing in the aftermath of some metaphysical tornado. These are more than readymades, and Holley is more than a Deep South Duchamp.

In fact he’s today’s most visible standard-bearer of what is called self-taught African-American art. Frequently hallucinatory and troubling, the visionary works made by sculptors, painters, quilters and assemblage artists from the rural South are increasingly collected by establishment museums and galleries. Holley is revered, and his music – really a performative extension of his art practice – has blossomed into three lauded albums and high profile touring. (He visits New Zealand in June for four concerts in association with the Audio Foundation).

Music is a fishhook for Holley – reaching a more instant audience than the visual art world can muster. Audiences accustomed to the cosmic-jazz and Afro-Futurism of Sun Ra and P-Funk are drawn to his loose-limbed, meandering keyboards and vocals. It’s mystical, frequently transcendent and always has one eye on history.

“It’s up to us to do what is necessary to let the whole globe know of our ancestor’s struggles,” he says. “This is what occurred in y’alls history, and that’s going to make it better for us to go on, through not only our planetary history, but even in our expiration and what we are yet to encounter, as humans doing a together project.”

However, within this vision of unity, his music is agitating for something. It jitters and shakes like an open window.

The single from Holley’s new record MITH (Jagjaguwar 2018) is “I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America” – a churning, thickly-overdubbed swamp of echoing voices, trombones, drums, and keyboards. It’s a succinct and brutal calling card:

I woke up in a dream

In a dream, in death’s dream

As magnetic a presence as Holley is, the video for this song is not your usual ego-trip. Not only full of other artists and their work, the video is largely shot within an artwork – Joe Minter’s African Village in America. Backing onto a cemetery, it’s a garden peopled with stark metal and timber testaments to social justice, peace activism and the African diaspora. This elderly man’s handmade project is the chief cultural highlight of Birmingham, Alabama, and took thirty years to assemble. Collectors describe it as an art environment, or as ‘yard work’: protective, symbolic, deeply non-Western, and yet classically strange Americana.

One of the great practitioners of yard work was the Reverend George Kornegay, the caretaker until his death at 100 of an art environment of figures, altars and symbols displayed around his home on a Native American burial ground (purchased from the Cherokee by his father). Kornegay’s art was a vehicle for communication from the dead, and from God, to the living. Containing layers of symbols and spiritual traditions, the yard displayed teepees, tigers and blue stone circles. Now dismantled, only photographs remain, but even they seem to speak in a strange register. His daughter reported voices coming from the yard.

“Them rocks represent the unknown; don’t nobody understand the hidden mysteries of God.These mysteries belong to us now, but we still don’t know. Why the mysteries happens is unknown,” Kornegay told one interviewer. “I got some secrets I don’t tell nobody. You don’t have to tell all your secrets. There’s some of this stuff I don’t name.”

For a newcomer the self-taught art world feels mythical and subliminally active, rather than kooky, kindly or folksy. It’s shape-shifting stuff – suffering and haunted, vengeful and toothsome. It’s also increasingly trendy; Kornegay’s work received a New York gallery outing in 2017.

Near the end of the video for “Fucked Up”, Holley is shown asleep (or dreaming) in an old iron bed frame. An older white man, suited, sits at his feet. This is Bill Arnett, occasionally controversial art collector and founder of Souls Grown Deep, a non-profit that champions the self-taught culture. Arnett told the Washington Post, “I promise to God that if a white man had done this, there’d be a civic organisation dedicated to protecting and preserving and restoring it.”

Of course there’s an irony for a white man to be contextualising African-American culture, but Holley’s upending of art history can always use a loquacious carnival barker. (Arnett, Holley says, is an “angel”; his son Matt is Holley’s manager).

“Let it be known that by being in these (art history) books, we have a better chance when we come together, and do what we gotta do for the spirit, from the beginning to the ending of our life. Because we are not talking about the ending of all civilisation – I don’t think that’ll ever occur – but I think there’s some gonna be some parts of the earth that are either gonna be washed away, or burned away. People talking about ‘this is the end’. This is the end happens every second!”

After the flood, after the fire, comes the gravedigger.

Nixie Jones Canady was Lonnie’s grandmother, and she worked in every department of the Poole Funeral Chapel, in Birmingham, Alabama. “She was a beautiful, strong, rare woman,” remembers Holley. His mother and father worked there too, and Holley was – he says – even conceived at Poole.

Nixie eventually helped dig the graves for three of the girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church terrorist bombing in 1963. Even as Dr King spoke to thousands of mourners, hundreds of clergy – and precisely zero city officials – the terrorists planted dynamite in the funeral chapel. Nixie went on to work at the landfill.

“She got a chance to see, every day, humans’ trash, garbage and debris, brought in by the truckload and dumped into these landfill sites,” says Holley.

“I went there with her at a very early age, so I got a chance to see what was being tossed, and thrown away, as waste,” he says. “From then on for me these burial places for humanity became like the landfills all over the US. If people only knew.”

This gothic intermingling of human life and death with piles of trash is Holley’s hallmark, a compulsion he can’t resist in the cemetery behind Joe Minter’s home. “I venture out and I look down into this little tiny hole you couldn’t even get your fist down into, and I shine a light down into the grave, and I discovered there wasn’t nothing there.

“I could only find the construction manner of the coffin, and the construction manner of concrete, and the construction manner of a vault that would hold a coffin. That’s just like the ruins of our city, of all these African-American communities.”

Through his art and music practice, Holley sifts through these ruins almost as a spiritual act.

“The only thing an artist knows from the time that they are born until the time that they die, is that they are under this protective spirit, and how we should be thankful for that, and go on with our life, and go on with our offering. Art to me is an offering to the spirits, showing them how much I appreciate my involvement in the continuation and in the passing it on, and on, and on.”

You can tell the uplifting triumph-over-adversity story of Lonnie Holley, where cosmically-minded music and art proves a force for renewal. You can recount his devastatingly bleak biography, and enumerate the violence and psychic suffering that are his raw materials. (Holley only took up sculpture in the first place to fashion headstones for two nieces, victims of a house-fire). Then there’s the third story of the celebrated artist with sculptures in the Smithsonian, fresh from touring European concert halls, the father and teacher who loves Mexican food and invites you to the merch table for a bumper sticker.

All those narratives would be true, but would miss the important sense that with Holley, he is really a ‘they’. Of course his art is distinctively personal, but there is a collective, ethereal voice too. If you listen closely, something is speaking through his work, fighting against erasure, using the broken bits of America at their fingertips. Something is seeing through his eyes, and working through his hands.

Though he’s 69 years old, Lonnie Holley isn’t slowing down anytime soon. With only a couple of days at home in between tours, he meets with students, announces plans for a tour with venerable Saharan desert musicians Tinariwen, and looks to new horizons.

“There is a time to plant, and a time to harvest, and a time to pluck up the roots, and a time to shake off the dirt where you can plant new seeds.”

“So if we go by that, there is the earth, therefore plant in it and you shall get a new harvest,” he says. Sometimes, too, there’s a force of nature at play.

“If you do nothing, nothing, then the earth gonna grow wild. It’s still gonna keep growing. You gonna have to go out and discover what the earth grew wild on its own.”

Lonnie Holley will be performing four Audio Foundation shows June 14 – June 19, in Dunedin, Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland. You can buy tickets right here.