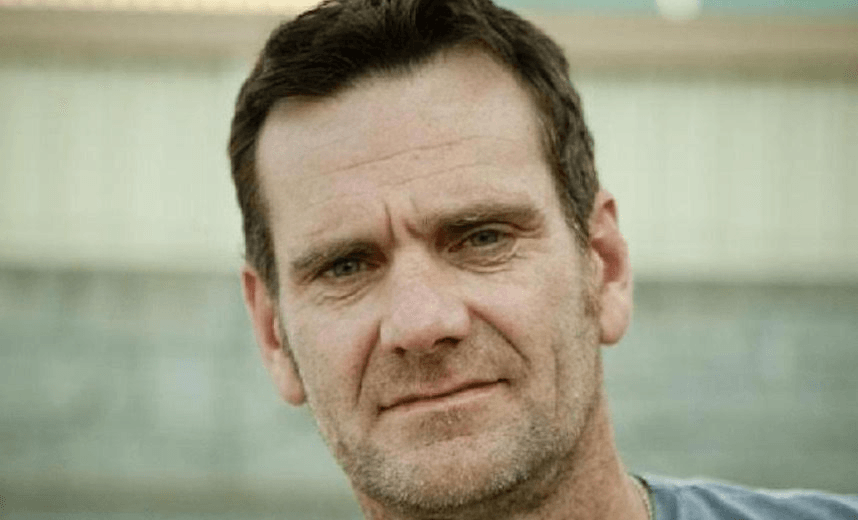

Henry Oliver talks to Campbell Smith, music mogul and the man behind Auckland City Limits, about bringing the festival back after sitting out a year.

“Anyone got any drugs?” Campbell Smith, a man who has done nearly every business-y thing it is possible to do in New Zealand music, yells to no-one in particular as I take a seat in his office to talk about Auckland City Limits, the festival he launched in 2016. “Paracetamol, ibuprofen, anything like that,” he clarifies at slightly lower volume, before looking at me.

“Haha – anyone got any drugs!” he says again to me, predicting the opening of this article.

I’ve just been sitting in the foyer waiting for Smith to get off what seemed to be an important, wheeling-and-dealing type of phone call. It’s the week before the lineup announcement and I’d been told by the festival’s publicist that I should be able to see it before I talk to Smith so I can ask him about specifics. But when I arrive things are apparently still very much up in the air. But it’s exciting. The festival, an extension of the Texas-based Austin City Limits (which this year expanded once again to Sydney City Limits), was cancelled for 2017 after Smith failed to secure the right act to close the show and draw a crowd big enough to fill Western Springs Arena. Taking a year off was a risk, but coming back with an underwhelming lineup would be death, so the first announcement had to be big.

“You work on it for an entire year and you’ll be amazed how much of it comes down to the last 24 hours,” Smith says as he washes down a couple of over-the-counter painkillers and I press record.

This must be exciting times, announcing the lineup. Especially after missing last year.

Yes, it’s cool. It is exciting. It’s fun. It’s good to be doing it again. I missed it last year.

When you announced that you were skipping a year, lots of people must have thought that was the start of the end.

Yeah, but what can you do?

Were you certain that you’d be able to come back?

It’s a long-term plan. It was never our intention to skip a year but I had this vision of what I wanted it to be and what kind of lifespan I think it can have and how it can grow. It would have been foolhardy to do one year that went really well as an opening and then to [have] a second year that was not going to be what I wanted. So the downside was that no-one got a festival that year, but the upside was I didn’t damage it. The only real problem, long-term, with taking a year off is I’m getting older and closer to death. I want to make sure this thing gets established and grows and becomes what I think it can do before I die.

And the weekend that it was scheduled for ended up with torrential rain…

Torrential rain? That’s polite. I took a video because my apartment is up the road from Western Springs. You can kind of see down over it. I sent it to my partners in America and they thought I was at a waterfall. Rain never normally stops a festival going but that might have. We wouldn’t have been able to build it.

Yes, there were rainy Big Day Outs, but nothing like that.

There was one amazing Big Day Out. People were pulling hoardings off the side and using them as rain covers and then other people were surfing on them. But that at least happened on the day of the show, so it’s built. The problem with rain leading in, like a huge rainstorm lasting 10 days, means you can’t build in it. Can’t drive a forklift on a grass field where it’s a mudslide. So, that would’ve been tricky.

At the time you talked a little bit about how there were acts close … Multiple acts close and there was an ideal lineup, kind of almost there, but not there.

Booking the Big Day Out, a well-known, established event, it was in agents’, managers’, artists’ minds when they think of planning their schedules. You have to do two or three of these shows before that process is something that starts in an agent’s mind. You got to get over that. And then they want to know who else is playing. Increasingly, they want to know what time they’re playing and who else is playing against them. And there’s always an overwhelming demand for darkness.

I remember the last Big Day Out we did, people were furious that we scheduled Deftones against Pearl Jam, and that was primarily because Pearl Jam were already on the bill when Deftones came on. They were playing two hours on the main stage. Deftones insisted on playing in darkness. So there was really nothing else that could be done. But people don’t understand that sort of thing that goes on.

How do you get the first ACL to jump?

It’s never really one at a time. In advance, you’re looking at what you want to present this year. You look at all those artists that would fit into a jigsaw that would make a show work. And then you kind of identify who you want to target as headliners and then from that basis you start going out and making offers. But you’re not offering one at a time, you’re talking to multiple agents. And also, the agents have ideas. You’re talking to them about one of their artists and they go, “What about this? What about that?” You just have a grid and the grid generally has lots of names and lots of holes. It’s not really a matter of who jumps first, but you need to get the top done earlyish because that impacts a lot of other decision-making.

In the heyday of the Big Day Out, the way that music worked in the culture was different to now. There were more acts that were universally loved. Pop culture has frayed into more but smaller niches and there are fewer of those artists that have broad appeal. So is it harder to book now than it was 10, 15 years ago?

What’s harder about it now than it was in the heyday of the Big Day Out, is that really that was all there was. And it was such a cultural phenomenon as well. It was a rite of passage event. Which, in the end, probably was part of its demise because there was a certain level of complacency in how that show ran.

We’re still not trying to be all things to everybody. It’s not a pop festival. It’s not an iHeartRadio and it’s not top 40. It’s not like just an open canvas. It’s a little bit controlled, in terms of what we’re trying to do. But it doesn’t feel to me to be any harder to book this kind of event than it was in the last years of the Big Day Out. The hardest thing about doing Australia and New Zealand is just … It’s not even actually the reality of how far away we are, it’s the perception of it. If you say to artists that are based in LA, “come play in New Zealand or Australia,” they’re like, “ah, no. That’s impossible. I can’t possibly.” And I say to them, “Do you fly to London regularly?” And they go, “Yeah, but that’s London.” Well, it’s the same amount of time. You’re just going in another direction. And it’s a slightly facetious comparison because, of course, in London you can go play hundreds and hundreds of other places within a short drive. You come down here, you’re basically coming, playing here and having to go back again. But the distance is certainly a factor in making it harder.

The hardest thing we face is getting the feel of the festival right and getting the artists who are going to fit with the kind of vibe that we’re trying to create, which is more than simply just putting on 70 bands on eight stages. This is a more holistic entertainment experience we’re trying to offer. It’s in the centre city so most of our audience can walk or get there easily and don’t need to worry about parking cars. There’s the kids’ things. There are lots of artists. There’s a real focus on food. And then the environment. You’re in a grass-covered park with a lake and trees, whereas the Big Day Out was in a concrete monstrosity in an industrial area.

There were aspects of the first ACL that were innovative for a festival in New Zealand – the kids’ area and the open drinking of mid-strength beer – and which gave it a different vibe to many others. Are you continuing to refine those ideas? Are you introducing any other new ideas?

Those core elements are all going to be there again because they’re the things that I think are the flagpoles of what we’re trying to do. And really the music fits in and around that. I don’t know that there’s particularly any new things that are happening other than just trying to develop those things. I’ve got lots of great ideas of what we can do in the kids’ section because it was really successful. I didn’t quite know how that would work but, fortunately, it worked exactly as I’d hoped. Parents brought their kids, spent the day there until four or five and took the kids home and came back. Or someone came and picked the kids up and then they went and had dinner. Some of them kept their kids there the whole show.

That’s one of my abiding memories of that show, too. It’s always the little kids on dads’ shoulders with the giant builder’s earmuffs. And that’s a pretty good snapshot of what I think festivals look like now. Fifteen years ago it may have been a 15-year-old upside down in the gutter.

And with the mid-strength beer, I wanted a wet site. It was important that I didn’t cage people anymore. There’s that overriding image of the Big Day Out where the stage is down one end, and there’s a bunch of people behind an 1.8 metre fence drinking beer. I wanted people to be free to move around. So that felt like a reasonable concession to make and I think the upside of people moving around and having a drink is you’re not consuming so much. I think everyone’s behaviour is kind of moderated by it. This is getting a bit anthropological, but I think when little kids are on site, it moderates the behaviour of older people. It’s the vibe. And it’s not a lamer vibe, it’s just more relaxed.

There’s now a Sydney City Limits. How’s that changed your job?

It’s made booking a lot easier. The struggle with 2016 was that it’s very hard to go out onto the market and say, “Can you come and play a show in New Zealand?” It’s a really long way away. It’s a tiny-ass market. And you’ve got to really have something to do in Australia. I don’t think anyone’s ever really come here and played and not gone to Australia. So having two festivals makes it a little bit easier.

You’ve been doing this a long time and seen a lot of bands play these things. What makes a great festival act?

I think those bands that really embrace the festival environment, the outdoors-ness, the moving nature of an audience and trying to spread your reach throughout the whole festival and bring people in. It’s a challenge. There are bands that accept that challenge, those are the ones that play good shows. Whereas if you play a show at a town hall or Spark Arena, you’re going out on stage to an audience that is already awed and they’re all focused on the stage and they’re there to see you. I think you really need to work to catch audiences beyond the hardcore fans, those kids that stand in front of the stage.

Through the years of doing Big Day Out, one of my favourite things that I would take out of each show was when you programme acts that people may not have heard of or the fanbase is small and they do that. And Kamasi Washington was a good example in 2016. There’s not a lot of people who would go, “I’m all over Kamasi Washington.” But the amount of people afterwards that go, “Who the fuck was that?” I was amazed. They’d go and get a burger or something and heard him and watch the whole thing. And people who came out of the Big Day Out over the years say, “Well, my favourite band in the world is X. And I first saw them at the Big Day Out.” I love that. I really love that. Because that’s what I feel is part of our job as well. It’s not just to give you 30 bands that you know inside out, but to give you broad offerings and things that you might discover and become fans of.

This is going back a-ways, but there’s an artist called Pendulum. And we had them on the Big Day Out, two o’clock in the afternoon. And I didn’t really know much about them. I heard the music and was like, “I don’t know if that’ll work.” And I was in a meeting with the police, I think. And I came out of the meeting and was like, “What the fuck?” The entire field of Mount Smart was jammed and you could feel the ground moving. I enjoy that surprise. I didn’t realise that band was going to have that kind of an impact at this moment in time, this was going to be what the kids wanted to just get off to. And they did. It was blazing sunlight and we’d only been open for three hours.

There’s are a lot more acts coming to New Zealand now, but there’s only so much a market can bear…

It’s a tiny market. It’s a very, very small market.

… So people have a certain amount of money that they can spend on live music. How difficult is it to deal with that? Two summers ago, there were maybe three festivals that went under in less than a month.

Yes, yes. It’s hard. What you just described is the paradox of promoting. You never can tell. Well, you can tell sometimes but it’s very rare. The key thing right now, is the traffic is intense. And, again, you go back to the glory days of Big Day Out, there was no Spark Arena. That has had an enormous impact on touring in New Zealand, having that high quality, high capacity venue has brought so much more traffic through than would otherwise come through from Australia.

Even below that, I’m looking at that week right after the Christmas holidays where there’s a tonne of headline traffic coming through from Falls Festival in Australia. That week of the 8th of January, there’s just like three things a night. And I know this because two or three of them are ours and it’s like, geez, it’s really hard work. And you know that if any one of those shows was on its own in that week it would have been gone [sold out]. But you’re right. People are like, “Okay, if I want to go to every one of these shows that I want to see here, I’m going to have to pull out $500 to go to these shows.” Which, I guess, gets us back to the attractiveness of a festival as at less than $200, you can see way more than five bands.

But do you have more booking options now that it’s harder to make money off records? For most artists, if they want to make a living they have to be on the road so much they eventually have to come to Australia and New Zealand.

There’s a lot more bands touring but it’s still not the easiest thing in the world to get them to come down here. I still have to really present a good case for it. And if there are more artists touring, there’s a lot more traffic coming through, trying to get the discretionary dollar of the audience in a very small country.

If you’re in a place like Austin for Austin City Limits or Chicago for Lollapalooza, just the population bases there… The audience there is 80,000 plus a day which is minuscule compared to the population catchment where you’re drawing from. Whereas here, you’re pretty much asking one percent of the population to come the show, which is insane.

One percent is not just a lot of people but a lot of types of people. Do you have to think about how different types of people would go through the festival?

Yes. Totally. You want to create threads through the day. So you want to say, ‘this kind of a person, this sort of a fan is going to go here, here, here, here’. You don’t go to ten things. It’s ‘what four things will they do and where are they?’ For that core audience of a certain artist, you don’t want to be giving them a Sophie’s choice of where they have to go. So you create [a plan] for the hip-hop kids or the parents or the 16-year-old girls. It’s broad generalisations, of course, but try to plot pathways for them.

And when you programme, you go, ‘this segment of the audience is going to want to do these two things and I need to get something else in this area, this kind of artist to fill whatever hole for that pathway’. The jigsaw bit is fun and it’s frustrating.

And it must work in reverse, too. There are going to be lots of people who aren’t going to want to see something, and what can you give them?

Yes. And you’ve also got to do that thing where I’m saying, ‘What are you going to discover?’ So, this type of audience is going to see this thing but they’re going to exhale there, or stroll past this or hear that and that’s going to be something they’re going to really want to hold on to.

And it’s cool if you can see a band win over the people that are waiting for the next band on the same stage.

Particularly when they’re flip-flopping stages [two adjacent stages, with acts switching between them] there are people just standing there. That’s the awkward part of playing a festival, when you’re flip-flopping stages. They don’t tend to have that much overseas. It’s really an Australia, New Zealand thing. So, it’s a bunch of people standing there looking vaguely at you but not really caring.

And the audience are also taking up space close to the stage.

But, if you pull them in … I think Neil Finn was telling me about Crowded House being followed by Metallica. And that was a trying experience.

Auckland City Limits is at Western Springs Stadium and Park on 3 March 2018. Spark has an exclusive pre-sale for Spark customers, available 9am, Monday 30 October to 9am, Wednesday 1 November.