Nichole Brown returned to her marae to bury her daughter’s whenua. She writes of giving back to the land she loves to build the family she has.

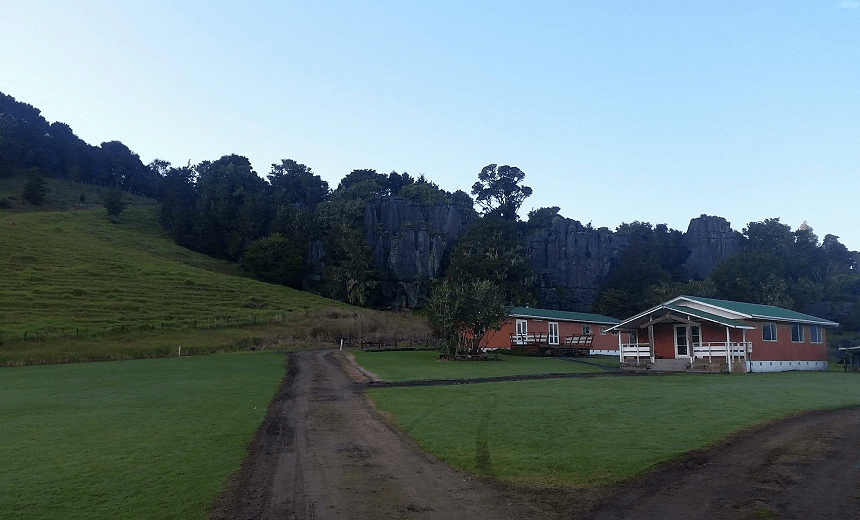

I cannot think of a more perfect place to spend our final night in New Zealand – cuddled up under the freshly painted walls of our marae, looking out across the blackened valley as the thick fog cover creeps in, and gazing up at the same starry skies that our tūpuna once used to navigate these lands.

Our marae. Named by my great grandfather’s generation after the four mighty tane from generations past – Tawai (my great grandfather), Riri (father of Tawai), Maihi (father of Riri), Kawiti (father of Maihi). Just five generations separate my Koro from Kawiti – the beginning of our line, and the last person to begrudgingly sign Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

I grew up running barefoot along these rocky paths and grassy fields. This is where we sucked the eyeballs out of the juicy heads of tāmure (snapper), there seemed to be an endless supply of lamb shanks for us to gnaw on, and the mouthwatering crack of golden takakau being cut while still piping hot was enough to rustle us quickly into the wharekai for a meal.

The cliffs were always out of bounds – the are sacred historical burial sites, and while they are beautiful, we have learned to appreciate their beauty from a distance. The glow worm caves were always fair game though. We learned every nook and cranny, we knew the difference between a stalactite and a stalagmite before we could count reliably past ten, and the glow worms were as familiar to us as the stars were to our ancestors.

And then we stopped coming here.

For too many years we just stopped coming. There were no manuhiri to welcome, and no one to karanga them up the path, the hot water ran out, and the gardens surrounding grandma’s little pink cottage became overgrown. The wharekai was locked up, and the air inside grew cold with neglect. While the business our whānau ran thrived, the core of us – our marae – was forgotten by most.

But not by all. There were few who remained and fought for our home to be restored. The locks were removed from the gates, new keys were cut, and slowly new life was breathed into the walls. The old curtains came down, and the green walls were covered with Opononi Grey. New pillows and mattresses were ordered, and the old ones were dragged down the front steps of the mahau never to be seen again.

Then the people came. Our people came home. And even when it was cold, there was a warmth and glow from within.

Today, our last whole day in New Zealand, has been the most special day for me since the day my daughter was placed against my face for the very first time. Today, with my beautiful mama to my left, my beautiful kōtiro to my right, and a fledgling mānuka with pink budding flowers at my feet, we finally returned my baby’s whenua to Papatūānuku. The part of my broken body that nourished and grew her inside of me is now nestled under this little tree, giving it the sustenance and life it needs to thrive.

This is tikanga tuku iho – it is the essence of who we were and who we are. We return everything to Papatūānuku and we tread lightly on her belly as we do so.

But this should not have been my first time here, on this hill, boots covered in mud and new life sprouting all around me. And it is here, in this moment, that my only life’s regrets have at last come home to rest.

This should not have been my first time here.

I lost three babies before I was blessed with my golden haired daughter. These three little babes taught me how to love by first teaching me the most extreme loss, and I was too broken to respect their journey, and the role they played in my journey. I never brought them home to rest. Today as I pushed the little mounds of earth back into place, I was finally able to let go of the three souls that take up so much of the air around us, and return them home too.

These babies are the only secret I have kept from my daughter, the only words I could never muster the strength to find. What would she have been like as a younger sister? How would her life had been if she was one of two, or three, or four? Or the most unthinkable – would this sweet little girl ever been given to me if even one of these babies had stayed with me?

At last, I have laid these questions to rest, and all the regret I have held onto for having brought them home is at rest on this little grassy hill too.

These grounds are tapu – they are sacred. And they are only ours. There will be no cattle grazing haphazardly through these hills. There will be no intrepid wanderers exploring these forests. There will be no noise, no disruptions, no disturbances here.

Only rest. At last. For them. And for us. This is where my peace will live.

At last.

As I write this, I can hear my Māmā and the sweet strains of her guitar, her singing voice ringing out from the kāuta as she plays the old songs for her moko as they run around her feet. The smell of mānuka smoke fills the air, and that smoky air is filled with love. Between songs she speaks in English, telling tales of the battles our tūpuna waged, and every now and then she comes to a Māori word that has no English counterpart. She explains the depth of the word as best as she can with such soul and eloquence I forget that I am talking with the same woman who used to scold us for not doing the dishes.

When all we see is a carving, she reminds us gently that this is our pouwhenua, and every detail – even the selection of the weathered tōtara, have their part in telling the story. The ochre colour of the paint, the place in which the carving was done, and the men who did the carving, every single part of this process has meaning.

Where all we see are tunnels, she tells us history of these trenches and the bravery our people showed when the Europeans came with their bayonets and cannons. She speaks admirably of the innovation it took to defend these lands with bare hands, a few hand crafted wooden weapons, and laughs out loud at how short our mighty Kawiti made his own weapon due to his relatively short stature.

This is home. These stories are home. These songs are home.

And now that this part of us is safely buried in the earth here, we are safe to roam to the furthest corners on Papatūānuku knowing that our souls are grounded here.

Tae noa I turi ki tō taringa ka ako.

Until our knees touch our ears, we are still learning…

More by Nichole Brown: I’m sorry I white-washed your world: A letter to my Māori daughter

Nichole Brown is Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Hine. She blogs about single motherhood and much more at Happiest When Wandering.

Follow the Spinoff Parents on Facebook and Twitter.