Dr Jess Berentson-Shaw chats with Dr Ben Sedley, clinical psychologist, father of three, and author of Stuff That Sucks, a book about teen mental health.

Wellingtonian Ben Sedley is a clinical psychologist who works with adults and adolescents. He’s the author of the illustrated book Stuff That Sucks: A Teen’s Guide to Accepting What You Can’t Change and Committing to What You Can.

Ben, can you tell me a little about what a clinical psychologist does and how they are different from, say, a counsellor?

Clinical psychologists have completed a Masters or PhD in Psychology as well as a Postgraduate Diploma, which trains students in the practical aspects of clinical psychology work. All up it is about five years of training after your undergraduate degree and it includes a year and a half of practical work.

Clinical psychologists are evidence-led practitioners, so we need to keep up to date with the research about what treatments are the most effective whilst still maintaining flexibility and compassion in all our work. I tell the students I teach that they’re new to being clinical psychologists, but they’ve been human beings their whole life.

Tell me a little about your work with young people.

I completed my PhD in children and young people’s understandings of mental health and clinical psychology training about 15 years ago. Since them I have worked in both public and private practice with young people and adults. I also supervise students training to be clinical psychologists.

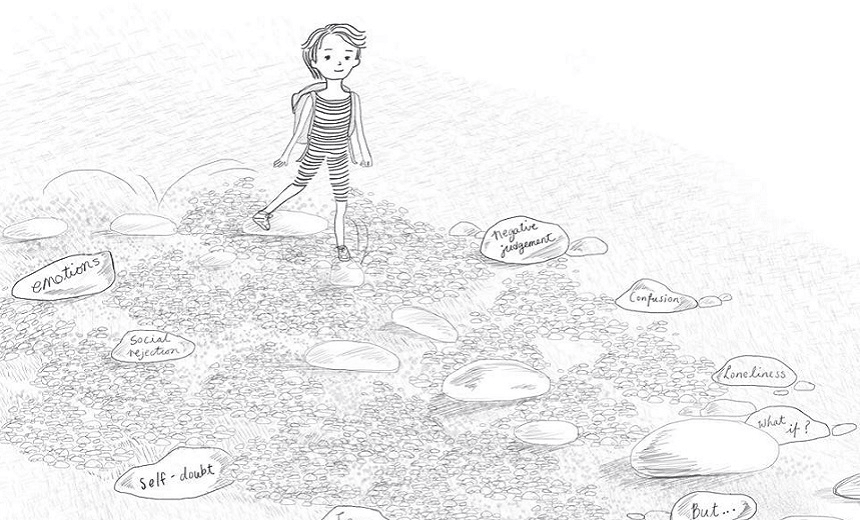

Mostly the work I do draws on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which helps people make space for mean thoughts and painful feelings rather than struggling against them, which then frees up a lot of energy to take steps towards things that really matter to people. I’ve found it’s a therapy that makes a lot of sense to so many of the young people I work with, because [they’re at the] age where you do so much thinking about what really matters to you and how you want to get there.

So lets talk about young people and mental health. I like to talk about the positives, not just the negatives of mental health, so from your experience and the research tell me – what does a mentally-well teen look like?

I tend to have a very broad definition of being ‘mentally well’. We certainly don’t want a society made up of people who all do and think the same things. To be a healthy teen, you need times when you’re happy, sad, angry, and worried. You’ll have times when your mind hands you confident thoughts and other moments or days when your mind is full of self-criticisms or worries about other people or the world and its future. You’ll have things you care about, even if they’re not the things your parents value, and you’ll do things that demonstrate what matters to you. So if you care about your friends, you’ll be a good friend, and if you care about the environment, you’ll actually do some recycling.

Unfortunately, caring about something invites a huge range of uncomfortable feelings. If you care about learning, you have to be willing to have worries about failing or disappointment if you don’t get grades that you’d aimed for. If you care about your friends, then you’ll want to be there for them even when they’re having a bad day, even if that leads to you feeling sad or worried.

Part of the challenge of being a teenager is to figure out what you care about and how you’re going to care about it. Often to do this you need to try a range of behaviours or appearances or views to see where you fit. And while you’re doing this, you have a brain that is developing quickly, so you might act impulsively or struggle to think through consequences or have a bunch of strong feelings that can feel unpredictable for you or others who are around you.

I do remember being a teenager was hard and complicated, and what you are describing sounds like really hard work for young people. I guess it helps us to remember that when we – the parents and adults in their lives – are struggling with their behaviour?

Teenagers have to go through this process in a noisy stressful world. The messages teens receive from family, school, friends and of course social media are intense, loud and mostly unhelpful. Teens get told that they can achieve anything, that they need to be happy all the time and that their success can be measured in number of likes or hits they get on Facebook or Instagram. Yet at the same time, the world isn’t happy most of the time, there are numerous blocks to success, short term options that are much more appealing than working towards long term values, and the cold hard reality that as soon as you start working towards one thing you care about there is less time to work towards everything else (so achieving anything becomes impossible).

Young people get told to deal with their emotions with impossible advice like ‘get over it’, ‘cheer up’ ‘don’t worry about that’. But trying to not have those feelings tends to lead us to have them even more, and soon everyday sadness and worries feel wrong and we engage in (often unhelpful) strategies to get rid of those feelings such as avoidance, risk-taking, drugs or alcohol, procrastination, and so much more.

What is going on for their parents while all this is happening? Where are the big challenges for the grown-ups?

Parents are worried about their children’s safety. New Zealand has one of the worst teen suicide rates in the world, numerous other teens are self-harming or purging food, abusing drugs or alcohol, engaging in risky sexual relationships, acting in violent or illegal ways or at risk from bullying from others. Internally, teenagers might be feeling depressed, anxious, or holding onto some scary secrets or memories. Some parents know that their teens are already struggling with these things, other parents are worried that they might be missing something or that their teen is on a dangerous path.

So it can be hard for parents too?

When I first meet a young person, I always ask for at least one parent (but hopefully both) to attend our first session, and with the teen’s permission, I start by asking the parents what they are most proud of about their teen and when they have their best times together. Some parents have no difficulty listing all the great things about their child; other parents can’t help themselves – they jump into their criticisms or disappointments. One of my jobs as a psychologist is to help parents see their whole adolescent again, not just the things that their child is doing wrong.

So at the point a young person or their parent has come to see you what is going on? What can help both the young person and their parents and the family generally?

If teens seek help themselves, they are often coming because they are struggling with anxiety or depression or other internal experiences. If they are dragged there by their parents it is for external behaviours like self-harm, drug use, or being difficult to live with; the teens may or may not agree that these are problems.

So in your expert opinion, and based on the evidence, when should parents be worried about their teens and seek outside help? What are the warning signs and signals and what should be their first port of call?

Parents are biologically programmed to worry about their children, so I would never tell a parent to not worry. However, sometimes those worries are connected to more immediate stresses such as a dramatic change of behaviour or withdrawal from engaging with the world (which might be studies, friends or everything). The first place to start should always be finding a good place to have a conversation and ask them how they’re doing. Talk about the things you’re worried about but don’t claim to have all the answers, instead be curious about how it feels for them. Their GP should be the first port of call, or if they won’t talk to their GP, see if your town has a youth drop-in centre or if their school guidance counsellor is someone they feel okay talking to. If you’re worried about safety, call the Mental Health Crisis team in your area.

Lets take it back to teens who may not be of any particular concern to their parents right now in terms of their mental health. What general tips do you have on how to keep communications open and functional during these years?

Everyone leads busy lives and it can be really hard for anyone in the family to have time to talk to each other, let alone about the big stuff that is hard to talk about. So the challenge for every family is to make sure that there are spaces for all conversations, big and small. Lots of parents I work with say that they have their best discussions with their teenagers whilst driving together, so if that’s the case for you, make sure those car trips happen. If you want your teen to talk to you about their worries or struggles, you need to be available to listen to them about everything and anything they want to talk about, whether its politics, music, what’s happening to their friends or bad jokes. Listening is the key, not jumping in with advice or corrections, but genuinely being interested in their views about the world, their interests, their relationships.

My kids are four and eight, and they are just pretty much a great big ball of “big feelings” a lot of the time, so we do lots of talking about feelings and naming feelings – just trying to be okay with what ever feelings they have and guiding them through being “the boss of their bodies” when want to body slam their sibling. Is there anything in particular you can advise doing when kids are little that will help build up mental health capital (so to speak) for when they are in the teen years?

One of the many hard things about parenting in 2017 is that there are fewer opportunities for low level disappointments, negotiations and independent problem-solving. Parents can help their younger children by naming and validating emotions (e.g. “seems like you’re feeling sad, can I give you a hug”) and then supporting their children to think of ways to manage the situation and predicting what the consequences will be for each option.

Do you think other adults are important in kids’ lives when they are teens?

Part of being a teenager is separating from parents, so there will be some things that they will find easier to talk to another adult about. Having said that, the more available and non-judgemental you are as a parent the better the chance they’ll be willing to share things with you too.

Any final thoughts on parenting teens?

Care about them and make time for them, even when they mess up. Especially when they mess up. Let them know that their feelings are okay, and that they’re loved to bits, even if their behaviours aren’t okay.

Ben can be reached on his website and you can follow the adventures of his book on Facebook.

Dr Jess Berentson-Shaw is a researcher and public communicator. She consults on effective evidence-based policy, and helps people and organisations engage the power of good storytelling to change minds. Follow Dr Jess on Facebook.

Follow the Spinoff Parents on Facebook and Twitter.