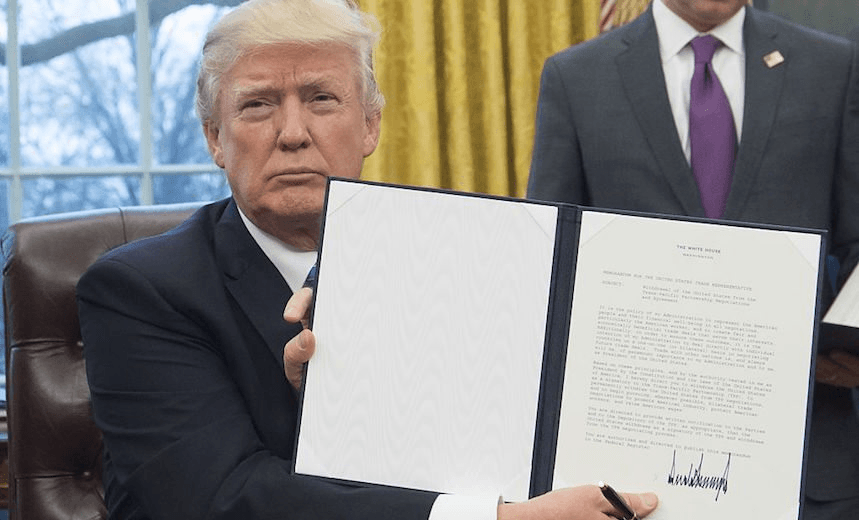

When President Donald J Trump signed an executive order withdrawing the United States from the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), a number of New Zealand’s trade cards flew into the air – including a possible bilateral deal with “America first”. Trade advocate Stephen Jacobi reviews the options.

The apparent demise of the TPP is is not the first time the core assumptions of New Zealand’s trade policy have been challenged. When Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973 we faced the herculean task of diversifying our economy while hanging on tooth and nail to our access for butter and sheepmeat. (How ironic that today we’re back again talking with Europe and Britain!) In 1993 when the outcome of the GATT Uruguay Round was in doubt, we made it known that New Zealand was open to the concept of high quality, comprehensive trade deals in the Asia Pacific region. That ultimately led to free trade agreements (FTAs) with Singapore, Chile, P4, ASEAN, China and TPP. This sort of FTA coverage was unthinkable back in the day.

Now we face a new challenge. Plan A – the TPP – has gone off the boil and Plan B, is, to quote Prime Minister English “tricky”. What is Plan B anyway? It is certainly not a retreat into “fortress New Zealand” which makes no sense for a nation dependent on trade. Nor is it a futile attempt to keep away from the controversial aspects of TPP and seek to negotiate more limited “market access-only deals” – this denies that the world has changed profoundly in recent years and companies are looking as much to investment as trade to drive their offshore business through multi-country “global value chains”. New Zealand is already largely a free market for others’ exports – most of them don’t see the need to reciprocate.

One key advantage today, which was not the case in 1973 or 1993, is that we have options.

Plan B is likely going to be a mix of things, both in the Asia Pacific region and beyond. Among the latter are the emerging NZ/EU FTA and a possible post-Brexit FTA with Britain.

In Asia, there is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a complex trade negotiation involving 16 economies, including Australia and New Zealand. RCEP also includes China but is not led by China, (as some commentators insist on believing) but by ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations). RCEP has been underway for a number of years and is grinding on at a slow place. Whether that quickens as a result of TPP’s demise remains to be seen. India is a reluctant participant and the current level of ambition in the negotiations is not high. RCEP at present is not an alternative to TPP, but is a useful initiative nonetheless – and could be particularly so for New Zealand if it delivers better access to Japan and India which we currently lack.

Then there is the TPP(11) option. As of today Japan, a key player, has said TPP is “meaningless” without the United States, while other players including Australia, New Zealand and Singapore have expressed interest in exploring the options. Japanese reticence needs to be seen in the context of their critical security relationship with the United States. On the other hand, Japan, like New Zealand, has already ratified TPP. We need to let some quiet diplomacy proceed to see if the remaining 11 parties, or a sub-set of them, see merit in amending TPP to take account of US withdrawal. This should include deciding whether or not to strip out of the agreement those things that were essentially US demands. It’s too early to jump to conclusions; the TPP ratification process has in any case another year to run.

TPP (11) would not deliver the long sought after FTA with the United States. That’s a gap that needs to be addressed. While China – under our shortly to be upgraded FTA – may have replaced the United States as our top trading partner, the US remains as important to us today as it was the day before the Presidential inauguration. America is not just a major trade and investment partner – it is a powerhouse of innovation, entrepreneurship and business ideas. New Zealand now has to find a way to engage and work constructively with the new Administration, even as we look to advance other options for growing and future-proofing our economy.

The way ahead for this initiative is far from easy. New Zealand has been seeking to obtain a bilateral FTA with the United States since the turn of the century. Two problems have bedevilled that effort: first, a poor political and security relationship, which has now been fixed, thanks to efforts over years by certain politicians and diplomats on both sides, supported by leaders from business and the wider community. And second, on the economic front, the small size of the New Zealand economy and the perceived – if highly exaggerated – risk which our agricultural sector poses to American farmers.

This will make it difficult for New Zealand to get ahead in the queue and may make a purely bilateral agreement ultimately no easier to negotiate than TPP. While we simply do not know the detail of the new President’s trade policy, he is not likely to do us favours on agriculture and may seek to go beyond the TPP outcomes on issues like investment and intellectual property. Nor is likely to be any more flexible on allowing professionals to work temporarily in the US as many services exporters especially in the tech sector would wish.

There is much irony here – TPP’s lengthy negotiation was in part because the other 11 partners were seeking to counter the full extent of American ambition across a range of issues as well as a wider framework of trade rules for the region. This was largely achieved: the final TPP text was a carefully structured consensus, which represented a balance of interests of all parties. For New Zealand TPP delivered substantial benefits with little change to existing policies, even if we did not achieve all we hoped.

Trade negotiations are the art of the possible. New Zealand does not have the luxury of closing off options before they have been fully explored. We’ve been in this space before. Making trade great again will require us to be nimble, open to new thinking and patient as we see where those trade cards fall.