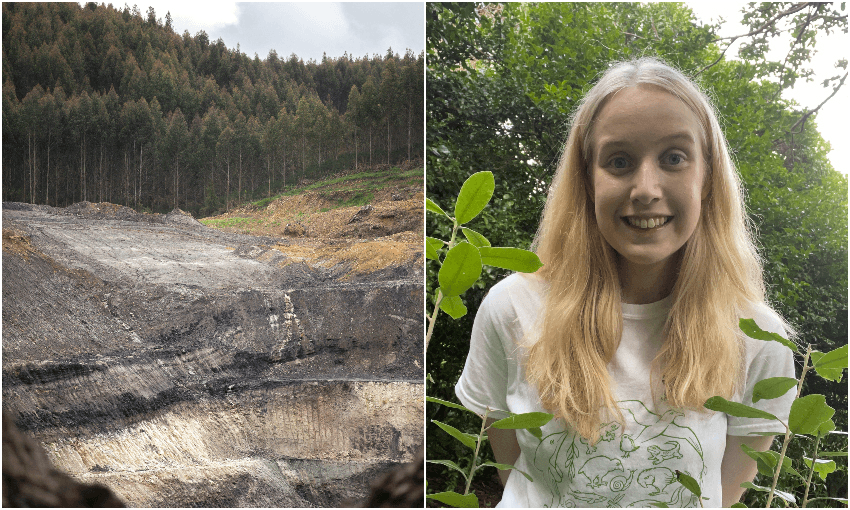

Gemma Marnane is on a mission to end mining in her small Southland town, even if it puts her at odds with the community and her own parents, writes Local Democracy Reporter Matthew Rosenberg.

In rural Southland, coal is black gold.

The controversial fossil fuel has turned the wheels of industry in quiet backwaters for longer than most residents can remember. But change is blowing a cold wind down the hill from the Takitimu mountains into Ohai and Nightcaps.

Last month, one of the region’s longest-standing mines, the Ohai mine, announced it was closing up shop after more than 100 years in the business. At the same time, another is looking to enter the market at a council-owned forestry block nearby.

Up in Wellington, 1000km north of both sites and the town she grew up in, 20-year-old Gemma Marnane finds herself in a unique position.

In August, Forest & Bird announced it would take Southland District Council to court for allowing exploration at the new site. As Forest & Bird’s youth communication manager, Marnane is now challenging an industry which remains the lifeblood of the two small towns she still calls home.

But she isn’t afraid of battles. Her life began with one when she was born three months premature. When Marnane entered the world, she was so small her father’s wedding ring fit around her wrist, she says.

The early start and ensuing challenges have given her a mantra she’s carried into adulthood: life is a miracle.

“I guess that’s what drives me to want to make change and speak up,” she says. “I’m so lucky to be here, to just exist. So I think it’s really important that lots of people see the value that our lives have.”

For Marnane, this philosophy has led her to dedicating her life to looking after what she loves most – nature.

Marnane’s family didn’t stay in Invercargill long after she was born, and she spent her entire childhood in Nightcaps, population 300. Before she was born, both of her parents worked in the nearby Takitimu mine, and hold different views to her regarding the environment.

“Working in the mines is quite a prestige thing, it’s quite a risky profession. It is something that’s seen as heroic, in a way,” she says.

But Marnane has always felt like the odd one out. In primary school, education was at times directed towards coal mining, and she has vivid memories of going to the Ohai site for a school trip.

While all the other kids were fascinated by the machinery, Marnane was unsettled, but couldn’t quite figure out why.

“Throughout my whole life, I’ve seen myself as an outsider. I’ve had different opinions, and I haven’t been able to express those,” she says. “It wasn’t normal to have different opinions, especially being so young.

‘‘In an ageing community, it doesn’t really fit.”

Marnane refused to let the differences in worldview stop her from speaking out. She joined the Southland District Youth Council in high school, but again, felt like an outsider. While her main concern was Southland’s environment, her peers were more interested in local infrastructure.

In 2019, she filled out an application to run in the general election, and even printed her own business cards, but was told by people at the council she was too young to stand.

Marnane understands the challenges. In rural Southland, the community is tight-knit, the industry entrenched, and change glacial.

Most pushback on a vision for a cleaner, greener future comes from people who make the argument that you can’t just “turn the lights off” on the coal industry, Marnane says.

But she remains optimistic solutions can be found that benefit everyone, and believes effective pathways forward will involve transition instead of instant eradication.

“I am so hopeful. I know Southland has such a plethora of sensational nature and something that’s so important to our economy. It’s what people come to Southland for.

“I think there’s a huge opportunity here to transition away from coal and have a future with jobs that last, and are sustainable and equitable.”

The community might take some convincing, but Marnane is in it for the long haul.

Climate change is a “now” issue, she says, and one day she plans on returning to the region which set her on the path she now travels, in part, alone.

Her parents have asked her to take a step back in her activism because of what is at stake for both parties, but she has no plans of slowing down any time soon.

She is thankful they taught her to find her own voice.

“If some people get to see my story, hopefully they’ll get to see this is so much more than just an environmental case,” she says. “This is the life of me, and other young people in Southland.

“I’m going to go back to Southland and live there for the rest of my life. I’m going to be a ratepayer, so I have a say in this too.”