I grew up knowing I was a descendant of one of the world’s most inspiring examples of peace and non-violence, but was ashamed to find it meant so little in my own country. Today’s reconciliation event is a powerful sign that is changing, writes Jack McDonald

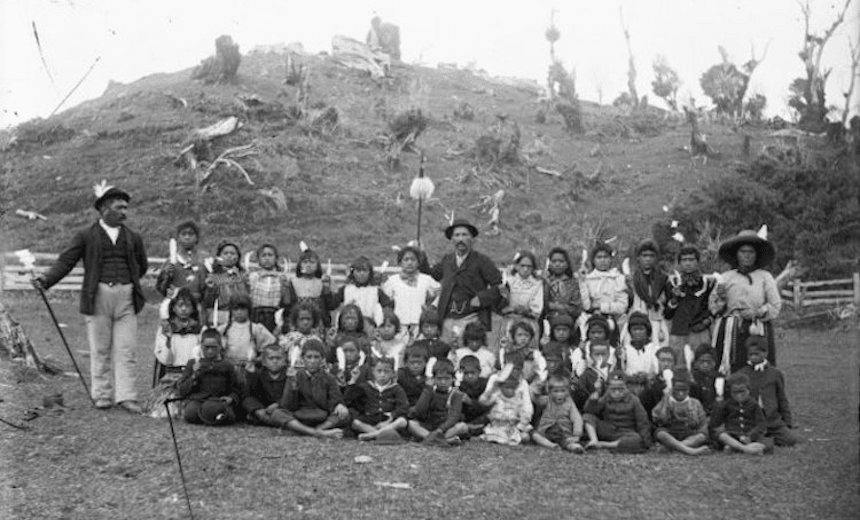

At 5am on November 5, 1881, 1,600 soldiers and policeman in the Armed Constabulary, led by Native Minister John Bryce, invaded the Māori settlement of Parihaka in central Taranaki. They were greeted not with armed resistance or hostility, but by singing children who carried baskets of food. The several thousand residents sat quietly on the papakaingā and offered no resistance to arrest. The Crown’s military force were welcomed to the community with open arms.

The peaceful welcome was not responded to in kind. The settlement was looted and destroyed and many women and children were raped by the colonial soldiers, a particularly horrible crime our kuia have held onto in oral histories. To this day, this crime has gone unacknowledged by the Crown. The men were shipped away. Many of them never returned and some were buried in unmarked mass graves.

This was not the first time the Crown punished Taranaki Māori this way. My ancestor, Hoani Tautokai, was imprisoned and sent to Dunedin with hundreds of others from the Te Pakakohi iwi in 1869. The iwi were almost driven to extinction after their south Taranaki lands were confiscated and invaded by the Crown. Tautokai, a name I now carry, never returned. My whānau have never been able to find out what happened to him.

And so, for me, just learning my own whakapapa and the history of my people was a political act. I grew up in the shadow of massive political events. My grandfather, Archibald Baxter, is the most famous of Aotearoa’s conscientious objectors. These twin traditions of non-violent resistance are woven into my psyche. Peace, injustice, intolerance and resistance: these were all concepts I wrestled with at a very young age.

The events of November 5 were the harrowing climax of a years-long campaign of non-violent resistance from the Parihaka community that disrupted the Crown’s confiscation and occupation of their lands. In the 1860s, on paper, the Crown had confiscated the entirety of the land in the Taranaki region.

By the 1870s, Parihaka had become a thriving settlement of thousands; Māori from across Taranaki and other iwi around the country joined the community to seek refuge from the ravages of the land wars. They flocked to the leadership of the settlement’s founding prophets, Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi. It was a centre of trade for Māori on the West Coast that established a bank and had even installed streetlights before New Plymouth.

As the Crown sought to carve up and sell off the confiscated land in the late 1870s, including the Waimate Plains, they forcibly removed hapū and iwi from the land.

The men of Parihaka employed non-violent tactics in response; they pulled down the fences and drew out the surveyors’ pegs as the Crown forces got closer and closer to Parihaka. As the men were arrested, more took their place. Over a period of two years, hundreds were imprisoned without trial and sent to the South Island for hard labour in inhumane conditions; some were detained in almost-airless caves on the Otago Peninsula.

The story of Parihaka is a profound symbol of Māori resistance to colonisation, war and land loss, and also a symbol of the resistance of indigenous peoples to oppression that has reverberated around the world. Te Whiti and Tohu are said to have inspired the non-violent tactics of Mohandas Gandhi’s satyagraha. He read about their struggles in the liberal press when he was a London barrister in the late 1880s, and early 1890s.

For too long the Parihaka story remained in a dusty corner of ignorance and indifference. A systematic “unknowing” took place within the Crown and the Pākehā establishment. Parihaka wasn’t recorded in official histories, and it wasn’t taught in schools until recently. Kids of my own and older generations knew more about the Gunpowder Plot and Gallipoli than they ever did about Parihaka.

Parihaka was even wiped from the map. In 1959, the government’s official Descriptive Atlas of New Zealand removed Parihaka and replaced it with a settlement called ‘Newall’, named after the military officer who arrested Te Whiti and Tohu in 1881. Many of the buildings at Parihaka, including Tohu’s Te Rangikapuia, fell into disrepair, and in 1960 Te Whiti’s Te Raukura wharenui burned down. As economic pressures bore down on rural Māori communities, the population dwindled to no more than a few dozen in the mid-1900s.

The community also saw many years of internal strife and dissent including splits between followers of Te Whiti and followers of Tohu and the various marae and the haukaingā who kept the home fires burning, and those of us who grew up away from Taranaki. An enduring legacy of colonisation has been division, even from our own.

There have been small steps to revival. In 1954 historian Dick Scott wrote a textbook for school students, The Parihaka Story, and in 1975 published his seminal history Ask That Mountain, which former New Zealand Prime Minister, Helen Clark, described as “one of New Zealand’s most influential books”. The books led to a rise in public consciousness, including the creation of striking pieces of literature and art. My own great-grandfather James K Baxter read The Parihaka Story and it influenced his literature and political activism. Other artists who have been influenced include Hone Tuwhare, Colin McCahon and Ralph Hotere.

The late artist and Parihaka historian Te Miringa Hohaia pulled some of this together, and commissioned new work, for the amazing Parihaka: The Art of Passive Resistance, a book that was launched with the Wellington City Gallery in 2000, including an accompanying exhibition.

My great-grandmother Jacqui Baxter, herself a descendant of Parihaka born less than 50 years after the invasion in nearby Ōpukane, contributed several poems to the book under her pen name JC Sturm.

In one of those poems, He waiata tēnei mō Parihaka, she posed the rhetorical question “Have you heard of Parihaka?”

The question has become somewhat of a rallying call of the nation’s collective understanding, or lack thereof, of the Parihaka story. It names the ignorance that defined Pākehā New Zealand’s understanding of one of the most striking stories of Māori resistance.

Its resonance also speaks to the desire from so many who have heard about Parihaka, to share what they’ve learned with as many people as they can find. It was even made into a badge that was sold at the much-missed Parihaka peace festivals, also driven by the imitable Te Miringa Hohaia.

We are well past time to make the closing lines of the poem a reality: “If you haven’t heard of Parihaka, be sure your children do, and their children after them. History will see to that.”

We can do that by ensuring that the New Zealand Wars including Parihaka is taught in all of our public schools. We can do it by establishing a national Parihaka day of commemoration. And we can do it, most importantly, by reconciling the past.

In recent years there has been a sustained revival of Parihaka culture and traditions, and the community has seen a renewed unity and shared sense of purpose, with a strong focus on te reo Māori and tikanga, health and wellbeing and community sustainability. Instead of the aforementioned peace festivals, the papakaingā now holds the Parihaka Puanga Kai Rau community festivals each June to celebrate the Taranaki Māori New Year.

Staunch resistance to oppression also lives on in Parihaka. Protesters blockading the New Zealand Petroleum Conference in Taranaki this February were led by Parihaka leader Ruakere Hond in chants of “kua hari, kua koa, kua tū te tikanga, kua haurangi katoa mai te ao” – even though the world has gone mad, we remain committed to the principles put in place [by Te Whiti and Tohu]. These same words were chanted on February 5, 1881 by the people of Parihaka to keep themselves strong in the face of greed and aggression.

Parihaka understands the work of Te Whiti and Tohu must go on. During the earlier stages of the treaty settlement process for Taranaki Iwi, dissent occurred between Taranaki Iwi and Parihaka because the process did not recognise their unique situation.

In April 2014, Taranaki Iwi and Parihaka wrote to the Crown outlining the aspiration of the Parihaka community to achieve self-sufficiency and reconciliation – a position whereby Parihaka can determine its own path.

Since then, Parihaka and the Crown have been working together to ensure that the history of Parihaka is remembered and never forgotten, and even more importantly, to ensure that the people of Parihaka are not defined by grievance and deprivation suffered by Crown aggression, but instead by the ongoing struggle to uphold and fulfil Tohu Kakahi and Te Whiti o Rongomai’s legacy.

Today, I will gather with hundreds of others at Parihaka papakaingā to commemorate a significant milestone on the journey to reconciliation between the Crown and Parihaka. The minister for Treaty of Waitangi negotiations, Christopher Finlayson, will deliver an apology on behalf of the Crown to the people of the Parihaka for the Crown’s acts of aggression. He and the Crown delegation, including MPs from all parties, will be greeted by a united Parihaka at the gate, as their colonial forebears were 135 years ago, but with peace, not aggression, in their hearts. It will be an extraordinary sight to witness.

This process offers hope for our future. The reconciliation package and financial redress will go a long way in the work to develop the papakaingā and in carving a new way forward for the community. It will help our people, young people like myself in particular, to return home to Parihaka and help realise our collective aspirations for future generations.

I was privileged to grow up knowing that I was a descendant of one of the world’s most inspiring examples of peace and non-violence, but was ashamed that it meant so little in my own country.

I will be able to stand that little bit straighter, and hold my head that little bit higher, knowing that my country remembers, and honours, Parihaka. Knowing that our community will be able to rebuild after decades of pain and division. Knowing that our Parihakatanga is a force that will continue to change the world.

This day will close one chapter in the Parihaka story, and will be remembered as one of the most significant milestones on the long road of the Māori people to achieve self-determination and self-sufficiency and in the ongoing work to achieve peace and justice in Aotearoa New Zealand.

As with so much of the Parihaka story, this was foretold by its founding prophets:

Kei te pakanga kē te matamata o taku ārero hei tāonga mō ngā whakatupuranga

E haere ake nei i mua i a tātou

Ko rātou hei kainoho i te rangatiratanga

Mō ake tonu atu

The very extremity of my tongue is at battle as a treasure for the generations

Which continue on after us

They will establish the self-determination

Forever

— Tohu Kākahi, 1895

Jack McDonald is affiliated to Taranaki Iwi and Parihaka-based hapū Ngāti Haupoto. He is the Green Party candidate for Te Tai Hauāuru

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.