Believe it or not, it is possible that Helen Clark is both the best option for the job of Secretary General, and that she is an important candidate because she is female

The first thing I heard on Tuesday morning: “Helen Clark is not running to be Secretary General of the UN because she is a woman.”

In some world there could have been a comma implied in that sentence before the word “because” – because she is a woman, she is not running – but not in the world in which Helen Clark was the prime minister of New Zealand for nine years, and then administrator of the UN Development Programme for the last seven.

A brief twitter exchange cleared up any potential confusion later in the morning, after Richard Blaikie referred noted the ambiguity of the RNZ headline.

@RBlaikie Nothing ambiguous about what I said which was that I have never asked 2 be elected because I am a woman. #Helen4SG @rnz_news

— Helen Clark (@Helen4SG) May 16, 2016

Helen Clark has often asked to be elected, and she is a woman. End of ambiguity.

And yet, for this woman to say she wishes to be considered for the job on the basis of her qualifications and experience, rather than her gender, was considered newsworthy. Why? Is it because this is what is assumed about women in general – that if they make it to the top, they do so “as a woman”, rather than for any other reason?

Of course there have been a wealth of comments about the process of election of the Secretary General, ruminating and expostulating and weighing in on her chances, and this has been going on since well before she announced her candidacy. I know this, as many New Zealanders do. Reportedly, geographic considerations may suggest the next person to head the UN should come from eastern Europe – which is inconvenient for our Helen – and I am pretty sure I’ve seen comment to the effect that the best antidote to her geographic disadvantage is that there is a general sentiment that it is time for a woman to take the top job. So don’t get me wrong: I understand the background of discussion and punditry that led to her response.

I also know perfectly well that Helen Clark was not addressing her comments to me.

This is precisely where things get tricky, though. I do not for a minute need reassurance that this is a job that might be given to Helen because of her gender, rather than because of her experience and qualifications: quite the contrary.

In contrast to the presidential election in the United States, in which the two party system in effect does reduce a candidate such as Hilary Clinton to the woman in the running, the UN contest appears more open. Parts of the process may be opaque, but there should be no need to categorise any of the contenders on the basis of their gender in opposition to the qualities of the other candidates.

Except that this is what we do. To women.

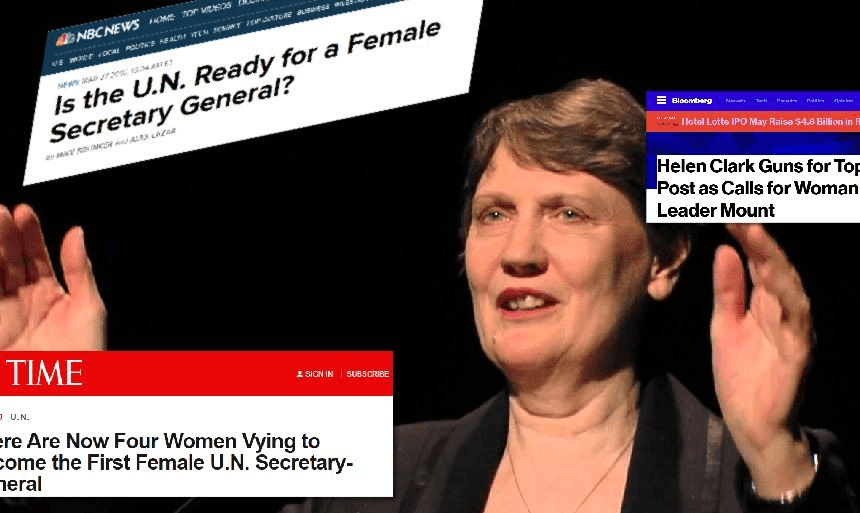

I understand very well that in order to be taken seriously for the job, Helen Clark needs to steer well clear of any implication that she is in a position to use her gender to her advantage. And there are plenty of headlines out there that walk the fine line between labelling her gender an advantage and a disadvantage, for the reader to interpret as they will:

Or, even more tediously:

Or there’s the twitter account, @She4SG, of the Campaign to Elect a Woman UN Secretary General, which unashamedly states, “We have had 8 male UN Secretaries-General and our 9th should be a woman.”

In brief, I get it: there’s a lot out there for her to respond to. But it still bothers me, because underneath it all, the rejection of the idea she is campaigning on the basis of her gender has more than a whiff of “not like those other women” about it. And I don’t think for a minute that this is what she intended: she wasn’t talking to me, she was talking to people who still think – in 20th century terms – that a competition on merit must necessarily exclude considerations of gender equality. The only problem is that when words go out to different audiences, different people can hear different things.

How many young women hear that they, too, will be judged on their gender? How many women learn that the question itself is not to be challenged – because if Helen Clark is not in a position to question the patriarchical assumptions behind it, then who the hell is?

Yesterday we learned that the University of Melbourne has “taken the extraordinary step of opening up jobs to female applicants only”, in order to ensure that their next appointments in Mathematics improve their ongoing issues with gender diversity, rather than worsen them.

A tweet on the news from the delightful Kate Hannah (@knhannah), who researches contemporary science culture and its depiction of women, started something of a discussion on New Zealand social media. Is this kind of affirmative action something we are ready for? Isn’t it extreme, to reserve jobs for women, and really unfair if you think about the individual men unable to apply for these jobs as a consequence?

Well, in short, the answer is probably yes. But it may be that it is still fairer, on balance, given that the data we have on the rates at which women are employed in fields such as mathematics, or the physical sciences, indicate quite clearly that the status quo involves unfairness in the opposite direction.

Balancing the scales is hard. On the other hand, we do this all the time: is the suggestion that the next head of the UN should come from Eastern Europe any less of an impediment to selection of the best candidate, on merit? Or is it a matter of trying to get the best form of representation we can, on average, over time?

I’ve written about this in the past, in the context of Nobel Prizes. We’re very happy to trade off the relative merits of one area of science versus another, and talk about whose turn it is: very happy, that is, until the conversation turns to gender, or ethnicity. When it turns to confront human privilege.

There’s a lot of emphasis on the need to employ “the best candidate for the job”, and that’s a fair principle to have in making any employment decision. It isn’t an absolute principle, however: if it were, we’d presumably be open to the idea that everyone’s jobs are up for competition all the time, and when the next person comes along with experience and training superior to yours, you should shuffle out of the way and make space.

We have employment contracts for good reason: we are people, and job security is important. But we should recognise that “the best person for the job” is only a principle applied within a narrow time frame, at the point of employment. Numerous studies of unconscious bias show how those hiring decisions are influenced by our stereotypes about the kinds of things different kinds of people are good at; and historical gender roles have a massive ongoing legacy.

So yeah: it is possible that Helen Clark is both the best candidate for the job of Secretary General, and that she is an important candidate because she is a woman, because these two facts are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that a university advertising jobs that only women can apply for is unfair, but that it is less unfair than if they didn’t.

This is the world we live in.