In the not too distant past, grieving parents were expected to move on, to count their blessings, to not be morbid. David Hill remembers friends who defiantly chose another path.

Warning: This piece discusses the loss of a baby and may be distressing for some readers

I’ll call them Graeme and Bev. I’m not using their real names, because… well, read on.

They were older friends of our own older friends, and nearly two decades senior to us. We knew them 50-plus years ago. Please note that distant time; it’s relevant.

Graeme and Bev had already been married a fair while. They’d found it hard to start a family, so when their GP confirmed that Bev was pregnant, they were 98 per cent delight, and the usual 2% apprehension.

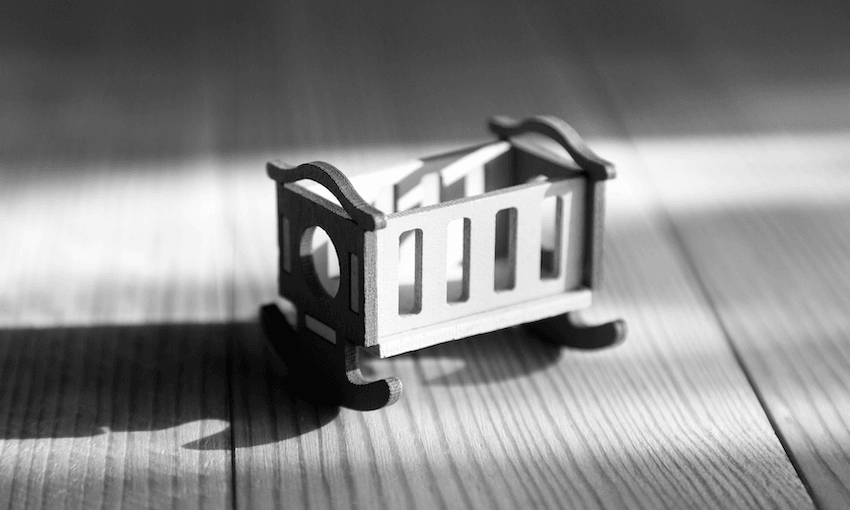

Things went swimmingly for eight months. They painted the spare bedroom, bought the cot, tried to choose between stuffed bear and stuffed duck, bought both.

Then came the morning when Bev realised the baby had stopped moving, felt heavy inside her. An ambulance swept her to hospital, where professionals did everything they could. But Graeme and Bev’s son was stillborn.

The hospital gave him to his parents to hold. That wasn’t usual in the 1960s, when stillborn infants were often whisked away instantly, and sometimes buried in unmarked or communal graves.

Then the bereaved parents went home to that newly painted bedroom (I’ve always wondered if they could bear to go into it), and started trying to put their lives back together.

In the hospital, Graeme had taken a photo of their son. I never saw it, but our mutual friends said you’d have thought the boy was just sleeping. Bev would hold the photo against her a lot; told our friends it made her feel their son was still there, somehow. Five decades-plus later, I can’t write those words without my eyes starting to fill.

Their church, meanwhile, would offer only a limited funeral service for the kid. He’d died before baptism, therefore according to the church’s tenets, etc, etc. I can’t write those words without my fists starting to clench.

They didn’t get over it. I don’t believe you ever get over such a wound. If you’re lucky/brave/committed, you presumably find ways to get around it, but it’s always there in the current of your life. I’ll stick my neck way out, and suggest that it should be.

But then the photograph began to cause problems.

Try to picture that photo. We’re talking the late 1960s, remember? A roll of film that you took in to a chemist or camera shop to be developed and printed. A colour image in this case, starting to fade to orange and green as they did then; slightly out-of-focus at the edges, I suspect.

People, in their church and outside, began suggesting to Bev and Graeme that it was a bit morbid, a bit unhealthy, even, to keep the photo of their stillborn boy on display. It was all right to show photos of dead parents or grandparents, apparently, but not of a stillborn.

Some even told them they should be more positive in their outlook, our mutual friends reported. They should move on, count their blessings.

But Graeme and Bev were resolute. Their son was part of their family. Having his photo was part of their healing process – though I’m not sure if we had those words to help us then. So the photo was staying put.

Then came the best, most deserved sort of happiness. Within a year, Bev was pregnant again. Their daughter arrived safely and easily. A son – another son – followed 30 months later.

They moved away from our part of the country soon after. We heard of them occasionally through our friends. We heard how their daughter and second son grew up knowing they’d had a brother, knowing also where he was buried, taking flowers there on his birthday with their parents. Twenty or 25 years later, when their daughter had her own first baby, she named him after her elder sibling, which I think is just brilliant.

Doing such things seems so natural now. Why conceal images or memories of your child because s/he didn’t live? We know now that it’s denial that is “morbid” or “unhealthy”, not acknowledgement and acceptance. We (mostly) accept there’s no justification for denying the unbaptised a full church funeral. Excellent websites like HealthEd and Whetūrangitia offer all the practical details you need.

We’re by no means perfect yet in our handling of death, especially a baby’s death, though we’ve come a long way, some cultures more than others. (And how grand to hear this week that parliament has unanimously passed legislation providing increased maternity leave for the parents of stillborn children, plus those who die at birth.)

What Bev and Graeme did back then was brave, defiant, daring. I’m telling you this ancient history for a particular reason. Bev died six months back, a couple of years after Graeme. As I said, they were a fair bit older than us.

They’re buried beside their elder son. Photos of them both are set into the headstone, next to a copy of that small, half-century-old photo of their firstborn that helped keep them going after his death. I don’t believe there could be a better ending.

Where to get help

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor.

Skylight: 0800 299 100 for support through trauma, loss and grief; 9am–5pm weekdays.

Whetūrangitia: Information for family and whānau experiencing the death of a baby or child.

Sands: Voluntary organisation supporting families who have experienced the death of a baby at any stage during pregnancy, as a baby or infant.