New Zealand martial artist Israel Adesanya will cross the threshold into legitimate worldwide superstardom this weekend when he fights the most dominant mixed martial artist in history.

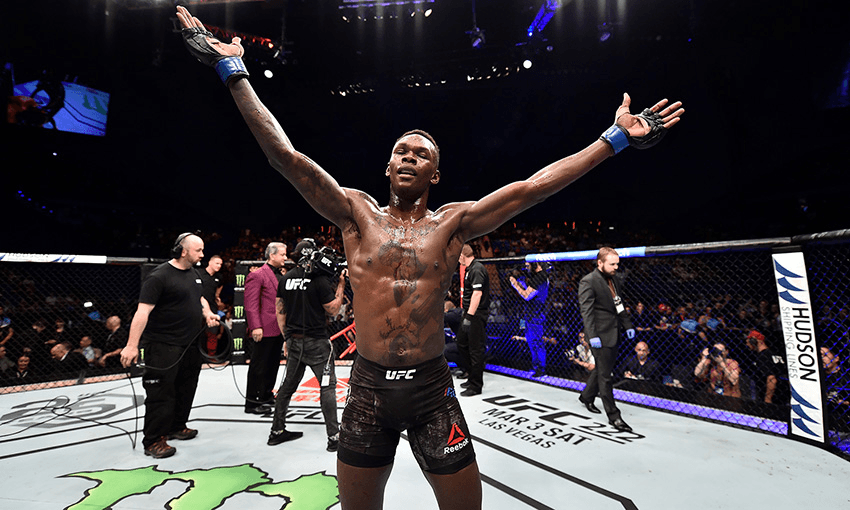

Israel Adesanya is near untouchable. With just two losses across more than 100 fights from Brazil to the Far East, Adesanya has captured the nation’s attention like nobody in martial arts, turning human cockfighting into watercooler chat through his undeniable charisma, inhuman athleticism and unapologetic arrogance. Last year, his first in the UFC, Adesanya won four fights inside of nine months, collecting seven figures and the breakout fighter of the year award.

“I want to be immortal,” he says.

At his best, Adesanya fights as if he’s phase shifting; as if he’s simultaneously in two places at once. To use David Foster Wallace’s description of Roger Federer, it’s as if he’s “a creature whose body is both flesh and, somehow, light”.

He walks opponents on to his strikes, baiting them in with the illusion of range only to blink momentarily out of danger – out of existence, like he’s just not there – materialising once his man is overextended to impale them with their own forward momentum.

“I feel like a shark,” he says. “That’s when I feel that animosity, I feel like a predator. My reptilian brain takes over, the human animal comes through and it feels primal.”

Comparisons to Muhammad Ali are premature, but that doesn’t deter the pundits. Whatever X factor elevates an athlete from the world of sports to pop culture, Adesanya has it. Where David Tua, Mark Hunt and Joseph Parker were and are fighters first and foremost, comfortable in a slugfest but ultimately a marketer’s nightmare, Adesanya is must-see talent. A dancer, model and undefeated fighter, last month eight different camera crews crowded Auckland’s small City Kickboxing gym for a shot of Adesanya. The UFC have thrown the full weight of their promotional muscle behind Adesanya – right now, he’s far and away the most hyped prospect in the world

But his opponent on Sunday is the greatest of all time.

For almost a decade, Anderson Silva was the face of the world’s premier organisation, the Ultimate Fighting Championship. A rangy kickboxer from a viciously poor family in Curitiba, Brazil, Silva was the first transcendent icon in a sport properly birthed only in the 90s. He moves like water; here crashing, here flowing, enveloping his opponents, dragging them deep and drowning them.

For seven years and 16 fights he barely lost a round. Fight after fight, Silva would make professional athletes look like pub drunks, exploiting their lack of speed, coordination and – most crucially – imagination, landing techniques that rightly should only be possible on movie sets. When Anderson Silva fights, it elevates the sport from violence to performance art.

Case in point: in 2009, three years into Anderson Silva’s 2,633 day undefeated streak, he moves up a weight class to take on 100kg light-heavyweight brawler Forrest Griffin, a one-time champion who saved the UFC from financial ruin when we he won the finale of their inaugural reality series The Ultimate Fighter in a gory brawl on primetime television in America.

It’s three minutes into the first round. Griffin, hard-nosed, meat-and-potatoes, has been knocked to the floor twice and is puffing hard. He plods towards Silva pumping out straight punches – right, left, right, – while Silva retreats with his hands at his waist, a step ahead, looking for all the world like he’s dancing a limbo. In some ways he is. Fighting takes place to beats just like choreography. Great martial artists will play with that rhythm, establishing a tempo, setting a pace – only to suddenly break it, catching their opponent midstep and off guard.

Battered and outmatched, Griffin’s rhythm now is predictable. As he lurches forward at a lazy 4/4, winding up for a third straight punch, Silva stops his retreat on the half-beat and drives forward, lancing Griffin with a single right hand and knocking him instantly unconscious. He falls, legs splayed, and paws at the air with his eyes shut. It’s comically grotesque. A year later, Griffin described it thus:

“Every fight I go into, I think, it couldn’t be worse than Anderson Silva. I tried to punch him and he moved his head out of the way then looked at me like I was stupid for doing it. He looked at me like ‘why would you do that?’ I felt embarrassed for even trying to punch him.”

It’s a quote that could be attributed to anyone on the receiving end of any of Adesanya’s 60-plus knockouts. And it’s the sort of soundbite the modern UFC lusts for. Originally a mob-financed passion project of a family of Vegas casino magnates, the UFC is owned today by the WME-IMG group – in other words, a talent agency. Where it was once the domain of freaks, toughs and the badly tattooed, mixed martial arts has made its home at the intersection of sport, circus and grotesque spectacle. Broadcasts show everyone from Anthony Kiedis to Cindy Crawford sitting ringside.

Read more:

‘I want to be immortal’: A few beers with prizefighter Israel Adesanya

Irish cultural phenomenon Conor McGregor was the first to capitalise on the new paradigm, recycling Rick Flair pro-wrestling aesthetics, Ali-esque banter and legitimate savant talent, he amassed a $100m-plus fortune inside of five years. While journeyman fighters regularly take sustained beatings for less than six figures, a select few become richer than they could imagine. Silva, though from an early, less affluent era, is worth upwards of $20m. But the price is dear.

MMA eats its own. Aging legends are routinely fed to up-and-coming fighters in a vampiric transfer of star power. After a certain point, the more legendary a fighter, the more keenly they’re sacrificed on the altar of business. The path to the mainstream is littered with battered and broken pioneers. But Adesanya’s coach, the understated genius Eugene Bareman, says they are prepared for a “vicious and crafty” opponent.

“Behind all the martial arts stuff, Silva is a ruthless competitor,” he says. “We don’t buy into it. We’re crossing our T’s and dotting our I’s.

Bareman, the second most-winning coach of 2018, has quietly built an elite stable of UFC contenders just off the motorway in Auckland’s Eden Terrace. Three of his students fight this weekend, including featherweight Shane Young, the first fighter to carry the Tino Rangatiratanga flag to the cage, and flyweight knockout artist Kai-Kara France. Adesanya, though, is Bareman’s masterpiece. Victory is vindication.

This Sunday the stakes couldn’t be higher.