In 1977, just months after the death of Chairman Mao, Harry Ricketts made his first visit to a nation finally emerging from decades in isolation.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

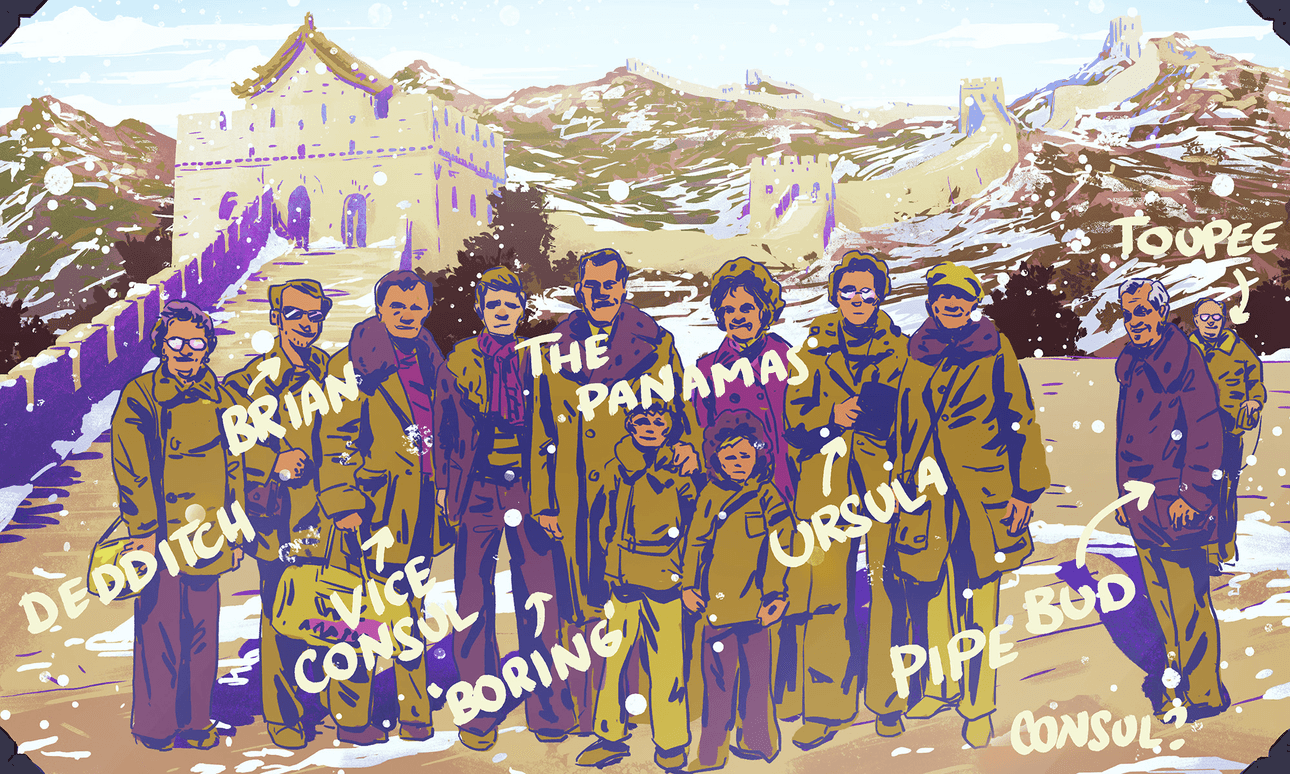

Original illustrations by Tim Gibson.

It was Ursula, my friend and colleague in the English department at Hong Kong University, who suggested we should go to China. We spent three weeks there in March 1977.

Our trip was only eight months or so after Mao’s death and the more recent disgracing of the Gang of Four, and visits were still only possible if you went as part of a group. Our group, led by a Canadian called Bud who had gout, chiefly consisted of diplomats and engineers, plus a few extras like Ursula and me. “Pipe”, as we nicknamed him, was from the British Trade Commission. The Panamas – the Panamanian ambassador, his wife and family – seemed to possess an endless wardrobe, always appearing in a different outfit at mealtimes. The Japanese consul and vice-consul were contrastingly immaculate, the former sombre in black, the latter smiling in Levis. Brian, “Redditch”, “Toupee” and “Boring” were engineers. There was also a historian and a geographer.

We left Hong Kong by train, jogging along to Canton past paddy fields and bare hillsides, revolutionary songs piped over the sound system. In Canton, the broad clean streets were lined with eucalyptus trees, and everyone rode bicycles. Outside the museum, children (like Kipling’s Kim) sat astride old cannons. Inside, the porcelain ceramics ranged from antique vases decorated with mythical beasts to their shiny modern equivalents depicting cheerful workers – these, we were told, had been made since the “smashing of the Gang of Four”, a phrase with which we quickly became familiar.

Over an early dinner, we quizzed the tour guide. He told us about the current education system: ages 7 to 12 in primary school; 12 to 17 in secondary school; then two years in a factory or a farm commune, followed by the possibility of university, depending on the recommendation of the community and some form of academic assessment. After yet another reference to the Gang of Four, Bud asked how the quartet had become so powerful. The answer, variants of which we heard at other times, was that Mao was getting old, that they had said one thing to his face while doing another behind his back, and that to challenge them had been dangerous, risking attack and imprisonment. We flew to Shanghai that evening, a red sun sinking over paddy fields laid out like lines of silver-papered chocolate bars.

The Peace Hotel near the Bund was out of an old movie, perfect for assignations and trysts. There was a massive, high-roofed entrance hall. Long richly carpeted corridors led to sumptuous, dark-panelled rooms, slippers waiting outside the door. There was even a cooked English breakfast. It was easy to imagine Bogart as white-jacketed Rick, lounging in the foyer, cigarette in hand, half a melancholy eye on the main chance.

Our daily briefings before and debriefings after our visit to factory or farm or workers’ residential area or museum had already begun to take on a set pattern. Tea would be served in tall cups with a hat to keep the heat in. There would be introductory formalities and civilities, usually including disparagements of the Gang of Four, succeeded either by a description of what we were going to see or a description of what we had just seen. (Brian was soon expounding a theory, much elaborated over the coming weeks, that the routine debunking of the Gang of Four served two purposes: to cast them as “devils”, scapegoats etc and, more realistically, to deal with the fact that China under Mao had been too repressive and so constantly to celebrate the “smashing” of the Gang of Four felt like a second liberation.)

On this occasion, we were to go to an industrial exhibition in the morning and a workers’ residential area in the afternoon. The exhibition displayed much modern work on silk and other materials; one needlepoint tapestry showed Mao in 1928, explaining to the Red Army the Three Rules of Discipline and the Eight Points for Attention; a lantern carved out of ivory depicted a pair of acrobats. There was a film of a lung operation, performed with a single acupuncture needle in the shoulder; the patient seemed fully conscious and was happily eating and drinking. A pianist played Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude.

The residential area, dated 1951, was apparently the first to be built after Liberation: two-to-five storey houses with gas, electricity, toilets, running water; kindergarten, primary and secondary schools; two hospitals, cinema, cultural centre, park, swimming pool, bookshop. The occupants were 90% industrial workers: “In the old society we used to go to the pawnbroker; now we go to the bank.” Men retired at 60, women at 50 (“manual”) or 55 (“mental”) on 70% of their old wages with free medical treatment: “In the new society we are provided with everything from the womb to the tomb.” Three-year-old children sang “I’m dreaming of seeing Chairman Mao” and excitedly wanted to shake our hands. In the evening, during a three-hour revolutionary opera called something like Red Guards at Hong Hu, I fell asleep.

After Shanghai, we spent most of the time in the north, in cities like Anshan and Dalian, visiting open-cast mines as well as the inevitable factories and communes. The engineers enjoyed tut-tutting about factory safety-conditions: “worse than Dickens”, as Toupee put it. It was in Dalian that one evening a misguided attempt at tour-party entertainment took place. ‘Rule, Britannia!’ was sung, also ‘Henry My Son’ and ‘Lloyd George Knew My Father’; Pipe contributed ‘Oh! Susanna’ on the Jew’s harp. The geographer, Ursula and I chain-smoked and declined to perform.

The trip finished up in Beijing at a more modern, but still plush, hotel. There were excursions to the Ming Tombs and the Great Wall. All I recall of the Tombs are great, bare, stone rooms, full of dull red boxes and coffins. On the Great Wall, it was minus 10 degrees centigrade, and we were muffled up in huge blue coats. In the distance we could clearly the snow-topped mountains of Mongolia. Only a small stretch of the wall had been restored, for tourist visits such as ours; the rest was, as I wrote in my diary, “broken & crumbling”. I thought of Qin Shi Huang (247-221 BC), first emperor of China, who both ordered the construction of the wall and had many books banned and burnt. Ursula quoted a bit of Ezra Pound’s ‘Lament of the Frontier Guard’. (Neither of us at the time knew of Edmund Blunden’s excellent sonnet about the Great Wall, written after his three-week visit to China in December 1955. The sestet achingly fuses his own First World War experience in the trenches with that of an imagined “new-set sentry of a long dead year, / This boy almost, trembling lest he may fail / To espy the ruseful raiders, and his mind / Torn with sharp love of the home left far behind.”)

On our last night, there was a formal dinner, every dish (except the jellyfish and seaweed) involving duck. As I noted down at the time, the main China Travel representative had an extraordinarily creased face, eyes “that were barely open” and a “massive, impassive jaw”. He spoke perfect English, but only used it in conversation; all official speeches and toasts, of which there were many, were done through an interpreter. Much mao-tai or moutai, a very popular distilled Chinese spirit, was consumed. The historian described the taste as like “12 horses farting in your mouth”.

On the flight back to Hong Kong, the group exchanged impressions. Perhaps not surprisingly, everyone claimed to have experienced exactly the China they had expected.

Postscript – After our group’s visit to the Forbidden City in Beijing, I wrote a poem rather different from any I had written before which was eventually published in my Selected Poems.

Peking History Lesson (1977)

I

in blues & greens

talking not looking

cheerful workers

amble or pedal

through the courtyards of the Forbidden City

under a whitening six o’clock sky

above each gate

Mao’s portrait

synthetically benign

the wart on his chin

just left of centre

as Lao Tse once wittily remarked

to Confucius: “times change”

ii

there used to be incense

& an ox and incantation

as the priests unrolled

the sacred silken scrolls

& the Son of Heaven at the hour appointed

took upon him the sins of his people

“we must learn from history”

said the guide with a smile

as we listened by the wall for an echo

& watched the workers

“educated morally, physically and intellectually”

walk in the sun

under the curved duck-egg-blue tiles

discussing perhaps the example of Lei Feng

who died on the job

hit by a reversing truck

fifteen years ago