Reservation Dogs isn’t just a history-making collaboration between Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi, it’s a crucial immersion into a world ignored, writes Sam Brooks.

There’s a scene in Reservation Dogs, the new comedy series from Seminole filmmaker Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi, that has to be one of the most up-front, simple condemnations of colonialism that I’ve ever seen on TV. It opens with an elderly white couple driving down the freeway. They go past a sign that says “LAND BACK, FUCKERZZ.”

“What do you suppose it means?” the man says, furrowing his brow. “I reckon the Indians did it,” his partner says, matter-of-factly. The man can’t comprehend it. “They mean the whole damn thing – they want the whole damn thing back?”

The woman responds, correctly. “I mean, the whites did kill an awful lot of ‘em and took their land so America oughta be ashamed of itself.” They continue trading stereotypes – the casinos, how being “Indian” gets you paid $1000 a month.

Then they hit a deer.

Hours later, the four kids at the centre of Reservation Dogs come across the dead deer on the highway and resolve to do something with it. They spend the rest of the episode with the deer in the trunk of their car, quite literally cleaning up the mistakes of two white people they don’t know, and who don’t give a shit about them.

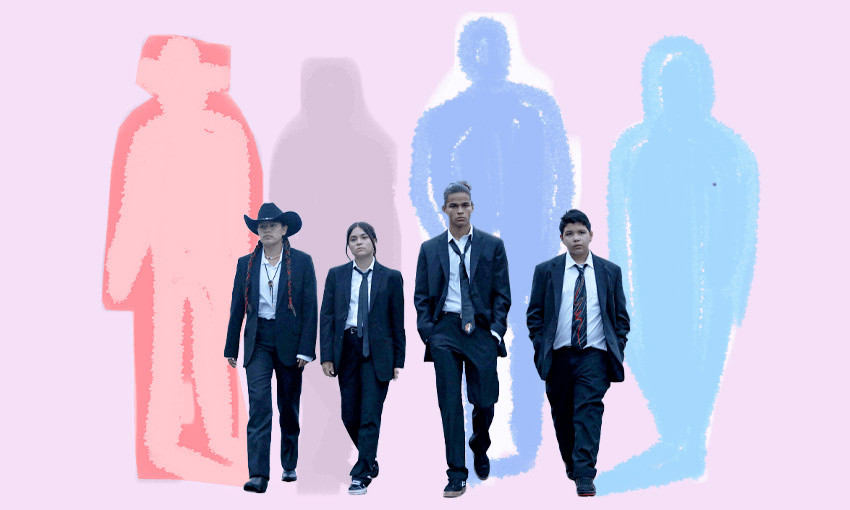

While the series might take its name from the hyper-violent, hyper-masculine Tarantino film, the Harjo-Waititi collaboration is a much gentler experience overall. Hell, other than the heist that opens the series, where those same four teenagers – Bear (D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai), Elora (Devery Jacobs), Willie Jack (Paulina Alexis) and Cheese (Lane Factor) – steal a van full of hot chips, this first season of Reservation Dogs is more set-up than pay-off.

That’s not a knock. Reservation Dogs has a lot to set up. This series is history-making for featuring entirely Indigenous writers and directors – Harjo has directing credits on three and writing on five, while Waititi shares a writing credit for the pilot and serves as executive producer – and an almost entirely Indigenous American cast. Right from the time the project was announced, it was clear that this series wasn’t going to be like anything else. The world of a rural Oklahoma reservation is not a familiar one – the audience has to be introduced to the world, the rules, and the ways that people interact with each other.

It’s a strange experience for me to review a series like this. Whenever I’ve written about my heritage, it’s been at oblique angles, and while I’ve often sought out Native American films, music and literature, it often feels like I’m looking through a window hoping to see my reflection. When I was younger, it was through Terence Malick’s The New World (a white man’s highly fictional, dubious lens on history) or the fiction of Louise Erdrich (deeply moving but hard to access for a snotty teenager). As I’ve aged and my desire to know more has opened up, the poetry of Joy Harjo, the music of Brianna Lea Pruett and the work of Elle-Máijá Apiniskim Tailfeathers have reached me right down to my marrow.

Despite being able to trace my lineage through generations – to a state, to a tribe – my heritage is more obvious on my skin than it is underneath it. Even then, I don’t read as Native American to the average observer; I read as “probably not white” – a half-right assumption, so therefore also a half-wrong one. My connection to my heritage is one of backfilling. It’s filling in the gaps in my own knowledge with stories, with text, with texture, wherever I can.

And it is the specific texture of Reservation Dogs that struck me most; it’s comedic but not slapstick, it’s downbeat but not depressive, and the magic realism sits comfortably next to the kitchen sink realism. Beyond the overarching narrative that the four teenagers want to make it to California to commemorate their dead friend Danny (and are willing to engage in petty crime to get there) there’s little momentum pushing the series forward.

Instead, watching the series feels similar to watching an expert painter draw a sketch, and then slowly, surely colour in between the lines. Each episode is more interested in illustrating a little bit more of the series’ world – an episode in a hospital here, an episode helping an uncle sell his ancient weed there – than it is getting these kids to their destination.

The gentleness is no accident. The pill has to be hidden in the pudding; even if there is much for the viewer to learn about the world, we still have to enjoy watching it. Thankfully, Reservation Dogs manages that balancing act, and achieves excellence in pretty much every regard: The four actors at the centre of it all deserve to be stars in their own right, while the writing blends dry humour and gut punches, often finding the harsh laugh in a bleak truth, and the brutal honesty in a mirthless chuckle.

There’s another moment where Elora asks if her uncle could tell her more about her late mother. After a few moments of silent consideration, her uncle simply says: “No, I can’t.” It’s understood why, even before he has to explain it – it’s simply too painful. These moments are peppered throughout the series, ones where hurt is swallowed, deferred or silently acknowledged. As the texture of Reservation Dogs gets coloured in, that’s the thing that rings truest and hardest for me: everybody knows where they come from. They know why someone is laughing, why someone is lashing out, and they know what to do when the white couple leaves the deer in the middle of the road. They put it in the trunk and make something of it.

Just like the deer in the trunk, a show like Reservation Dogs comes with a lot of baggage it has to carry through no fault of its own, solely due to being one of the first series of its kind. That’s an unfortunate burden for any text to carry; it can’t simply be a great story with gorgeous performances and stunning visuals. It has to be a 101. It has to be the introductory text. And so, in the case of this text, and especially in the case of this culture, it has to be an unlearning.

I want you to think of the first time you saw a Native American onscreen. Was it Pocahontas? Was it Peter Pan? Was it Dances with Wolves? Was it pretty much any Western film?

Now, I want you to think of the first time when you’ve encountered a story that depicts Native Americans as they live today. Here we have to say that no story is a monolith: the Americas are two tracts of land, with hundreds of Indigenous communities among them who could be grouped under the label “Native American”. But it is pretty likely your first exposure might come with clicking into this very Disney+ series.

I firmly believe that the first time we encounter something, that encounter gets imprinted on our brain, and we spend the rest of our lives adjusting that – whether it’s through enforcing that initial image, unlearning it, or somewhere between the two. If we’re incredibly lucky, those first impressions are ones we don’t need to unlearn. In most cases, however, we have to adjust and unlearn until we end up with an impression, a lasting image, that more accurately reflects reality. It’s a lifelong process, and one that’s often a lot less fun than watching Reservation Dogs is.

It’s why it’s important to make stories that are authentic to experiences, to cultures, to communities. If you fuck it up, you’re not just hurting everybody you’re representing, you’re hurting everybody who comes into contact with the story you’re telling. She might be your only onscreen exposure to the culture, but Pocahontas was only one Native American, and she sure as shit wasn’t anything close to a Disney princess. You can do your own unlearning on that one.

Chances are if you’re tuning into Reservation Dogs, it’s purely because of the Taika Waititi name being attached, and there’s nothing wrong with that – but also check out Sterlin Harjo’s films, he’s bloody brilliant. For me, the value of Reservation Dogs is twofold. One part is what the bulk of the audience will get out of it: an excellently made, thoughtful introduction to a culture that might have otherwise been a mystery. But the other part, the part that speaks most to me, is that it has given me access to a part of the identity that I carry with me, one that’s buried deep in me and maybe not so deep inside the land that identity comes from.

As Harjo and the team around him colour in the world of a rural Oklahoma reservation, they colour in a little bit of me, too.

The first three episodes of Reservation Dogs arrive on Disney Star+ today, and weekly thereafter.