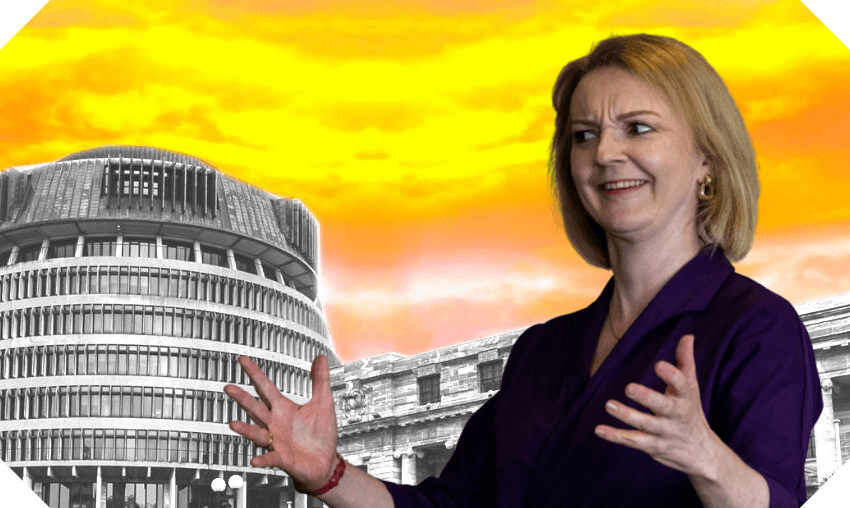

The disaster engulfing prime minister Liz Truss is a very British kind of political crisis. But MPs here should be watching closely, writes Henry Cooke.

Prime minister Liz Truss is in office but not in power.

Just five weeks after triumphantly entering Number 10 she has been forced into another humiliating backdown on one of her signature policies, and had to fire her best friend in politics – the chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng. Her party, the oldest in the world, faces polling so bad that an election tomorrow could see it tossed into the dustbin of history. The members of her caucus that aren’t openly denouncing her fill journalists’ phones with news of plots to replace her or well-worded putdowns.

Truss was never going to have much of a political honeymoon. She came to power as the country stared down a very scary winter of spiraling energy prices and possible rationing, her party very bruised by the events that sent Boris Johnson packing.

But to win the vote to replace him, Truss had promised a radical plan of major tax cuts, with no spending cuts to pay for them. This plan, combined with a huge chunk of new spending to subsidise energy bills, was put together into a “mini-budget” that also contained a surprise abolition of the 45% top tax rate.

Voters hated it, but the free market Truss wanted to woo seemed to hate it even more, selling off the pound and more importantly, UK government bonds, or “gilts”. This started a somewhat complex process that ended up playing havoc not just with mortgages but also with pensions, necessitating the Bank of England stepping to attempt to calm the chaos – something it has still not quite managed.

Over a few hours yesterday Truss looked to calm things down by announcing a second tax u-turn – this one on a plan to keep corporation tax low – and fired Kwarteng. If you need it in New Zealand terms, this would be a bit like Jacinda Ardern firing Grant Robertson and cancelling fair pay agreements, all in one day.

To a certain extent, this is a typically British kind of crisis, one where the country is forced to confront yet again that it no longer has the power to create its own weather. But there are lessons for New Zealand politicians too.

1. Mandates matter – as do the length of political terms

Boris Johnson won the Tories a smashing majority in the 2019 election promising voters two big things: “Getting Brexit done” and an end to austerity, with government spending used to advance areas that had been left behind as the country deindustrialised. This combination of right wing culture politics with economic policy more at home with Labour was immensely popular, and seemed set to provide Johnson with many years in power.

But like in New Zealand, voters don’t actually get to vote for one single prime ministerial vision or mandate, they vote for a party. And that party threw out Johnson and carried out a leadership contest to replace him. Truss won this contest not by appealing to her fellow MPs – a large majority of them preferred the more cautious Rishi Sunak – but by winning over the party membership, an utterly unrepresentative group of 80 or so thousand people who very much like the ideas of lower taxes.

Now the country appears stuck with an economic programme they don’t feel they voted for, with no election in sight until 2024, as the UK has five year electoral terms.

There are guard rails that stop this kind of thing happening in New Zealand.

On leadership itself, National elects its leader from the caucus and only the caucus, while Labour now only hands things over to the wider party if a leader can’t win a two thirds majority in caucus. This means most of the time the people who are deciding who should lead a major party (including when that person is also going to be prime minister) will be experienced politicians who know the person and their flaws well, and can see the problem with promising things vastly different to what voters want. (There is a strong argument that this is anti-democratic in itself, but that argument works a lot better when parties have actual mass membership, which is not really the case in New Zealand.)

We also have three year electoral terms, meaning the chances of the public being stuck with a huge change in mandate it didn’t vote for over several years is very low. Unfortunately, there is quite a push from some politicians to change this.

2. Backbenchers matter

Truss has been forced into these backdowns not just from voter rage, but from the way that rage has fed into her own MPs, all of which have seats full of angry voters that they could toss them out at the next election. These MPs have threatened to not vote for major parts of her plan, and always hold the potential to force a no confidence vote, which would see an election held far sooner than 2024.

This is a fairly alien situation in New Zealand, where extremely strong party whipping and MMP means MPs almost never rebel from their parties. We’ve seen some slight moves away from this with the Louisa Wall and Gaurav Sharma dramas, but nothing like the kind of open rebellion which would really endanger any actual policies, let alone the confidence of the house in the Labour government.

And yet. There is an election nearing, one where a whole host of Labour MPs are likely to lose their seats, even if the party scrapes out a win, just because the tide went so high in 2020. These MPs may be on the lookout for ways to differentiate themselves from the pack – or might just be sick of defending the Three Waters policy to every single person they meet on the streets of their electorate. One backbencher by themselves has basically no power – just look at Sharma – but if a few of them band together around a single issue things could get much dicier.

Do I think this is likely? Not quite. But it is something for Ardern and other party leaders to keep a close eye on.

3. People don’t like tax cuts for the literal 1%

The most controversial part of Truss’ mini-budget, the thing that roiled voters up and dominated headlines for days, also happened to be one of the smallest and least important policies: the scrapping of the top tax rate of 45%.

This top tax rate is only paid by people who earn more than £150,000 (NZ$302,000) – literally less than 1% of the UK. As it is paid by so few people, the actual amount of money that it cost to get rid of was pretty small – just £2b, compared to the tens of billions of pounds involved in the other cuts.

But it was the principle of the thing. Everyone was getting ready to tighten their belts for a very tough winter, interest rates were heading up (partially as a result of Truss’ budget), and the thing the government appeared to be focused on was tax cuts for the rich and a removal of the cap on bankers’ bonuses. It was the kind of stuff Labour strategists could have only dreamed of under Johnson, who would have seen the political nightmare of such a strategy a mile away.

New Zealand also has a top tax rate – 39% – that only about 1% of the country pays, introduced by Robertson in a clear attempt to bait National into promising to abolish it. National have taken the bait and promised to get rid of it, despite the easy Labour taunt that this would give thousands and thousands of dollars to some of the richest New Zealanders, including Christopher Luxon himself if prime minister.

It might not go off in Luxon’s face quite so spectacularly, but if National do retain this policy it will remain a potent weapon in Labour’s hands. Aren’t we supposed to all have tall poppy syndrome?

Follow our politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.