Labour implemented a lot of policy in its six years in government. How much of it will still be there in 2026?

This is an adapted piece from a pre-election post on Henry Cooke’s newsletter Museum Street.

Helen Clark managed to piss a lot of people off.

By 2008, her government had alienated Māori with its Foreshore and Seabed Act, social conservatives with its legalisation of prostitution and civil unions, social liberals with its refusal to touch abortion law reform, farmers with its “fart tax”, greenies with its GE stance, royalists with its replacement of the honours system, neo-cons with its refusal to invade Iraq, neo-libs with its vast expansion of the welfare system through Working For Families, and water enthusiasts of all stripes with its proposal to regulate showerheads.

And yet her successor left much of this policy architecture in place.

John Key, to the continuing despair of many on the right, refused to dismantle Labour’s biggest policy achievements, such as Working For Families, paid parental leave, four weeks of annual leave, Kiwisaver, interest-free student loans, the indexation of benefits, and Kiwibank.

Key did things to cut back on some of those big Labour policies, like removing the $1,000 grant that welcomed people to Kiwisaver, but the overall structure of these policies survived and even thrived under nine years of National.

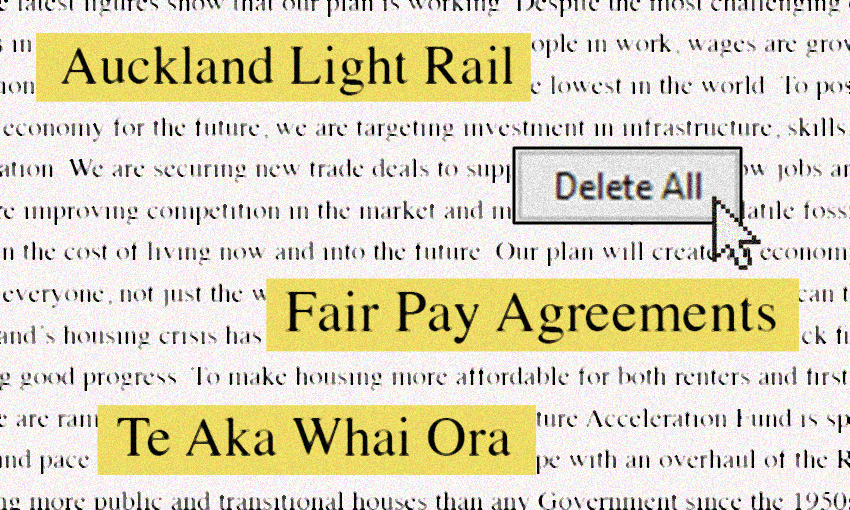

The most recent Labour government’s policy legacy faces a far more uncertain future under the new National-led government. The exact makeup of that government is still to be determined, but here’s a look at just how much the clock is going to be wound back to 2017.

Welfare

Labour made a raft of changes to the welfare system, introducing new benefits, boosting others and changing the way other benefits were actually administered.

I don’t have the space to pick apart every boost, but here are the headline changes:

- The introduction of the Best Start payment for new parents, which is universal in the first year and then means-tested.

- The introduction of the Winter Energy Payment for everyone on a main benefit, including superannuitants.

- Increased paid parental leave.

- The removal of many (but not all) benefit sanctions.

- The indexation of working-age benefits to wage inflation instead of CPI. This brought these benefits into line with superannuation and meant they were guaranteed to raise at the same rate.

- Increased benefits outside of that indexation in a bid to essentially erase the cuts from the 1990s.

- A huge range of changes to abatement rates for Working For Families and other benefits.

So how likely are these to survive under the new National-led government?

National has made clear that it will go back to indexing working-age benefits to CPI instead of wage inflation, saving it about $2b. This is a subtle change but will mean the annual increases for every beneficiary aged under 65 – whether they be a jobseeker or disabled – will likely be smaller and their incomes will gradually fall further behind those who are working or over 65.

The party has also indicated benefit sanctions are on the way back, including “money management” – where jobseekers aren’t actually given much cash but instead bills are paid for them.

It’s unclear what might happen to the more popular middle-class policies.

Paid parental leave is definitely not going to go anywhere given National has now made a lot of political hay trying to make it more flexible.

In 2020, National said it would means test Best Start but I can’t find that promise being repeated this year, or mentioned in Act’s alternative budget. I have asked the National Party about this policy and not received a response.

The Winter Energy Payment is a bit more complex. National has said it will keep it in place; Act is very keen to means test it. If NZ First is part of the government it seems unlikely it will be means tested for over-65s.

Legacy survivability rating: 3/10. Some of the big middle-class changes like paid parental leave will survive and National won’t “undo” benefit boosts. But the indexation change will mean working-age benefits will fall behind incomes.

Social issues

New Zealand has had seven prime ministers under MMP, and all but two of them have been “social liberals” – with Jim Bolger and Bill English both professing Catholic beliefs and generally voting against things like abortion legalisation.

The others – Jenny Shipley, Helen Clark, John Key, Jacinda Ardern, and Chris Hipkins – have all professed little to no religious belief and backed socially liberal causes to differing degrees.

There has naturally been a bit of chat about how a Christopher Luxon prime ministership could change that, given he is an evangelical pro-life Christian. But the nature of social policy in New Zealand makes it unlikely that much of what Labour has achieved in this space will be rolled back. The incentives to leave the status quo in place here – especially given his top team is quite liberal themselves – will be far too strong.

To recap Labour’s big policy achievements in this space:

- Decriminalised abortion.

- Created safe zones around abortion clinics.

- Changed the law so that trans people can change their genders on official documents more easily.

- Banned conversion therapy.

National has made an iron-clad commitment to leave the abortion issue alone – one that makes absolute sense given the party itself has plenty of strong liberals on this issue. Indeed if they tried, Act would likely look to stop them.

Similarly, a majority of National MPs voted for the conversion therapy ban and for the gender change bill, which makes it very hard to imagine the sixth National government looking to start another big fight over the issue.

Legacy survivability rating: 10/10. The law is settled.

Housing

Labour came into office in 2017 riding a wave of anger about the housing crisis. Its headline policy was a disaster and house prices and the housing waitlist have risen massively since. But there were some serious policy changes along the way.

- Used the planning system to encourage density with the Medium Density Residential Standard or “MDRS”. This new standard forced councils to zone all residential land in major cities for medium density housing, creating a right for developers and property-owners to essentially bypass local opposition and build townhouses if they wanted to – up to three storeys high.

- Put out a direction under the (now-abolished) RMA so that councils had to zone for housing up to six storeys near major transit nodes, and could not stop developments for lacking car parks.

- Banned foreign buyers from most residential property.

- Extended the Bright-Line test to 10 years.

- Introduced the Healthy Homes Standards for rentals.

- Banned no-cause evictions from rentals and introduced a new default whereby fixed-term tenancies rolled into periodic tenancies.

- Banned rental bidding.

- Limited rent rises to once a year.

- Eliminated interest rate deductions for landlords.

- Ended large-scale state home sales.

- Building or buying 5,600 state homes and 7,700 community housing homes, with thousands more planned.

- Created the Ministry for Housing and Urban Development and changed Housing New Zealand into the wider Kainga Ora development agency.

This is a big list of policies for the new government to unpack, but we know some things are for the scrap-heap.

National co-authored the MDRS and announced it alongside the government in the beehive, heralding a bipartisan consensus in favour of more dense housing that developers could rely on. But earlier this year, facing strong pressure from Act and angry homeowners who didn’t want their neighbours to build taller buildings, National went back on its word and said it would change the MDRS. As the whole point of these standards was predictability and stability for developers wary of the thousands of ways councils have to stop new housing getting built, this change essentially destroyed the policy, even from opposition. I have written about this issue at length should you wish to read more. Big picture, this will mean fewer homes are consented in the next few years than they would have with the status quo, as councils regain the power to say no.

National has indicated that it is comfortable with the direction put out under the RMA, known as the “NPS-UD”, so the planning law change seems safer.

The foreign buyers ban is supposed to be partially removed, with National allowing them to buy homes of $2m or more at the cost of a stamp duty – a key plank of the revenue National needs for its tax cuts. But if NZ First is needed to form this government that may not be tenable.

We also have a clear commitment from National to move the Bright Line test back to two years and reintroduce interest rate deduction for landlords. Act favour scrapping the Bright Line Test completely.

On wider tenancy law some things are clear and some things are not.

National has committed to re-introducing no-cause evictions and stopping the automatic rolling over of fixed-term tenancies into periodic ones. It is less clear where it stands on the Healthy Homes Standards (which it opposed when they were introduced) or other changes like the ban on rental bidding. I have asked for some more clarity.

On state houses, National has said it would match the current government track (but not the more ambitious one recently announced by Labour).

Legacy survivability rating: 4/10. Labour’s legislative pendulum swing in favour of tenants and allowing more housing to be built won’t be completely undone, and the state home build programme looks to be safe.

Education

Chris Hipkins was fairly busy in education before becoming prime minister, but a lot of the big promises from 2017 fell away. Here are the key changes Labour made.

- Introduced fees-free university education for year one and fees-free trades training for years one and two.

- Combined New Zealand’s 16 polytechs into one huge institution.

- Attempted an ambitious reform of NCEA with some bits finished (it’s free now) and some bits a long way off.

- Removed National Standards for primary education.

- Looked to end “voluntary” school donations by paying schools who promised not to ask for them.

- Made a range of changes to the way early childhood education (ECE) teachers are paid in an attempt to bring them to parity with primary school teachers and entice ECE centres to hire more qualified teachers – although this work appears to have paused.

- Took control of zoning away from schools and handed it to regional bodies.

- Ended the National government’s charter schools programme.

- Replaced the decile system with the “equity index”.

- Introduced 20 hours of free ECE for two-year-olds – although this doesn’t actually start until next year.

- Introduced free school lunches for schools in low-income areas.

Some of this appears safe under National. Despite opposing it at introduction, National has said it will not remove the fees-free programme. Act still wants to scrap it.

National has indicated it wishes to unmerge the mega-polytech, re-introduce something like the National Standards programme with a standardised public assessment, and re-introduce charter schools.

On ECE, National will scrap the 20 hours of free ECE for two-year-olds before it gets going, replacing it with a tax credit. It is not clear what exactly would happen to the funding for qualified teachers and the like.

Luxon has indicated that National will keep the school lunch policy in some form. I’ve asked what they make of the school donation policy and have not received a response.

When it was last in government, National was also interested in replacing the decile system so it seems unlikely that would shift. National’s education spokeswoman Erica Stanford has criticised the NCEA reform programme but from what I can see, has not quite committed to completely cancelling it.

While I can’t find a specific policy on zoning, Stanford was very critical of the move in parliament, saying school boards knew what was best for their schools.

Legacy survivability rating: 4/10. Changes are coming but the likely survival of fees-free is a fairly sizable win for the overall legacy, even if no Labour MPs are particularly keen to brag about the policy anymore.

Transport

Transport was one of the sixth Labour government’s weakest areas. It came into office talking a big talk about building light rail in Auckland – six years later there are no spades in the ground. In the same period, China has built 17,000km of high speed rail.

Outside of Auckland there are other delayed projects. Transmission Gully was completed outside of Wellington, but Let’s Get Wellington Moving faces serious hurdles. There have also been endless fights about various state highway funding streams.

But there has been some policy implemented alongside all these fights about marquee projects.

- Introduced a Road to Zero safety policy which prioritised investment on things like median barriers (although they continually miss targets for these) and on lowering speed limits in some areas.

- Introduced the Auckland Regional Fuel Tax of 11.5c (GST-inclusive) a litre on petrol.

- Introduced New Zealand’s first vehicle emissions standard, requiring importers to sell a mix of vehicles that reach an average tailpipe emissions measure or face fines. The idea here is that this standard can get cleaner over time and make sure manufacturers/importers are offering a greater range of low and no-emissions vehicles.

- Introduced a “feebate” whereby purchases of more heavily emitting vehicles pay a fee that is transferred (in theory) to a subsidy for a cleaner vehicle – whether that be an EV or just a more efficient car.

There are few areas where the divide between National and Labour is more clear than in transport.

National has promised to reverse the speed limit changes introduced by Labour’s Road to Zero policy. It is also canceling Auckland Light Rail, the Auckland Regional Fuel Tax, and the “feebate”. However a recent u-turn has seen National decide to support the vehicle emissions standards.

Legacy survivability rating: 1/10. Not much.

Health

Health is a traditional strong spot for Labour, as it tends to fund it at a higher level than National.

It certainly benefited from this at the 2020 election, when a response to the biggest health crisis in a century was rewarded with the biggest Labour vote in almost that long.

But the fact that National was more trusted on the issue suggests that some of its wider policy changes have not gone down as well. Here are the biggest shifts:

- Abolished the DHB system and replacing it with a national delivery entity: Te Whatu Ora, alongside Te Aka Whai Ora, commonly known as the Māori Health Authority.

- Introduced a range of new mental health support services, including a “frontline” free counselling service and services in schools.

- Extended free GP visits from those under six to those under 14.

- Abolished the $5 co-pay for prescriptions.

- Pursued a pseudo-decriminalisation of cannabis, allowing it for medicinal purposes and telling police to use their discretion before charging people for use.

- Legalised pill testing at festivals.

The big one is the DHBs. National’s health spokesperson Shane Reti has pledged to abolish the Māori Health Authority – but he’s less clear on unpicking Te Whatu Ora. National were opposed to the centralisation in the first place of course, but can quite reasonably argue that the disruption required to unpick it would not be worth it.

The frontline mental health services aren’t likely to be scrapped by a party that has been demanding the government do more on mental health, and scrapping the extended GP visits would look particularly miserly.

The $5 co-pay would be re-introduced as Luxon indicated after the budget. Pill testing at festivals is less clear – National opposed the policy but might not think the fight is worth it. Plus Luxon said he considered drugs a health, not crime, issue during the leaders’ debates.

Act is also very interested in reforming Pharmac, and has one of Big Pharma’s former lobbyists as a new MP in Todd Stephenson. The huge pharmaceutical companies hate Pharmac as its operating model is built on getting very good deals out of them and encouraging the production of generics. Many patient advocacy groups also feel that Pharmac is too slow to obtain brand new expensive medicines. Pharmac is one of the fourth National government’s most enduring legacies, but the party seems to have fallen out of love with it of late. It will be interesting to see what change it allows.

Legacy survivability rating: 7/10. Getting rid of the Māori Health Authority would take a significant chunk out of Labour’s policy legacy here. But if the DHBs remain centralised that will be a big achievement to look back on.

The workplace

The Labour Party likes to reform labour law.

Labour in government passed a range of workplace legislation. Some of this was basically resetting things to where they were under Helen Clark. Other changes have been more ambitious.

- Instituted a new Fair Pay Agreements regime that looks to set “floors” for pay and conditions for workers across entire industries, if not by negotiation then by an enforced floor set by the Employment Relations Authority.

- Banned 90-day trials for employers with more than 19 employees.

- Lifted the hourly minimum wage from $15.75 to $21.20. This six-year raise of $5.45 compared to a rise of $2.75 the six years prior.

- Re-instituted a general legal right to “rest and meal breaks”.

- Doubled statutory sick leave from five days to 10 days a year.

- Introduced a new public holiday – Matariki.

- A host of other smaller legal changes aimed at helping unions, such as allowing union representatives to enter a workplace without the consent of the employer in certain circumstances, changing timeframes for collective bargaining negotiations, and re-introducing a duty to negotiate in good faith if a union attempted a multi-employer collective agreement. These changes largely reversed a set of changes the last National government made in 2015.

This is a big list but workplace law is one of the main areas where you can really see a pendulum swing between Labour-led and National-led governments. It’s a policy area that is generally quite zero sum (when employees get more rights, employers get less, and vice versa), an area in which both party’s bases are very invested, and also an area where small bits of legislation can change quite a lot.

Let’s deal with them in order.

Fair Pay Agreements are anathema to both National and Act, who have promised many times to repeal them. There are seven FPAs currently at the bargaining stage which one assumes will be thrown out, although if National really wanted to it could allow these FPAs to exist as single little mini-laws. I highly doubt it given they are not in place yet.

National and Act have also repeatedly confirmed they would like to get rid of 90-day trials. ACT’s actually pushed for 12 month trials. I doubt NZ First would get in the way.

The minimum wage won’t go down under National but it is very unlikely that it will rise by the same amount. Act is keen on a three-year freeze on the minimum wage. That said, NZ First is much more pro minimum wage than National.

I’ve asked about rest breaks and have not got a response from National. Luxon has said he has no plans to reduce statutory sick leave, but Act wants to take it back to five days.

There’s been a lot of noise about Matariki after Luxon got himself into a bit of a mess suggesting that it should replace another holiday like Labour Day. He later clarified that, if elected, National would not look to get rid of any public holidays. Act said the party would remove the January 2 holiday to help small business absorb the cost of Matariki.

The other changes to union organising are likely to be somewhat reversed. Act has promised to repeal all of Labour’s workplace changes and National will likely see the arguments that they made for these changes in 2015 still make sense for them in 2024.

Legacy survivability rating: 2/10. Matariki and sick leave changes will likely survive.

Justice

Labour came into government promising to get the prison population down and has managed that – something the opposition argues has led to a rise in crime.

Finding the exact policy that led to this reduction in the prison population is not that easy. Some of it will have to do with judicial, prosecutorial and police discretion.

Here are Labour’s key policy changes in this area.

- Ended the “three strikes” sentencing law.

- Banned “military style semi-automatic” rifles after the March 15 terror attack, and introduced a gun register.

- Removed the blanket ban on prisoners voting, allowing those on sentences of less than three years to vote.

- Boosted legal aid.

It’s also worth noting that the Labour government was attempting to strengthen NZ’s hate speech laws but this was dropped as part of the great Bread and Buttering.

Three strikes will definitely return – National and Act are clear on that one. Act is keen to strip away the firearms reforms but will face some pushback from National on that – how much is unclear.

And removing the vote from prisoners? Last time National was in government it happened via a members bill. I can see that happening again, although the courts having had such a forceful say on the issue might stay some hands.

Legacy survivability rating: 0.5/10.

Climate

Climate has a minister but no ministry. It is one of the big meta-issues that will shape New Zealand’s public life for the coming decades, but it is so all-encompassing that often a policy that lives in another area has massive climate implications.

For example: The medium density residential standard which I mentioned in the housing section is arguably the most important climate change policy the last government made. Few things would get New Zealand’s emissions down more than a shift to people living in urban areas where they get to work and play without a car. But it is still a housing policy.

Similarly, while the Labour government never actually managed to charge farmers for their emissions, its moves on freshwater are generally expected to bring down methane emissions.

So this list focuses on things that are more squarely within the climate space, but will undoubtedly miss some of the bigger policies that will impact emissions.

- Introduced the Zero Carbon Act which sets emissions targets and budgets into law.

- Made some changes to the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – most crucially by capping the total number of “credits” for emissions in the system.

- Banned new exploration permits for offshore oil and gas.

- Allocated the money from the ETS to a huge range of decarbonisation measures, from getting rid of coal boilers to a deal with NZ Steel.

- Introduced a new Green Investment Fund.

There is a lively policy debate on whether everything bar the ETS is basically a waste of time.

Given the ETS is theoretically supposed to cover all emissions and there is now a cap on the number of “credits” that can be used for these emissions, the idea is that anything that takes away emissions without reducing the cap itself does nothing to reduce overall net emissions, because the same amount of credits remain in the system. Instead, these people argue, the ETS cap should be lowered gradually, which will in turn increase the cost of emitting and make the market work out how to decarbonise without government help.

This is a position now adopted by National – it wants to use the funding from the ETS for its tax cuts instead of direct decarbonisation projects. The counter-argument to this one – and one Labour favours – is that investment is needed now because the ETS cannot yet do the heavy lifting. They say you would need a carbon price five or six times higher than what it currently is to get these companies to make the climate investments they are now, and they doubt that a price this high would be politically feasible. It is difficult to see any New Zealand government supporting the ETS getting to a point where driving a petrol car becomes a luxury, for example. Hanging over all of this is the fact that our largest emitter – agriculture – isn’t in the ETS at all.

That debate is far too complex to go into detail on here.

But the big picture is that National would look to “stick to the targets” set in the Zero Carbon Bill but rely on the ETS to get there, instead of these other deals. The party is also keen to re-introduce new permits for offshore oil and gas exploration. Whether this will result in new exploration is another question – finding the oil or gas and then setting up the infrastructure to use it would take years, and at some point in the future Labour will hold office again, putting that investment at some risk.

Legacy survivability rating: 6/10. If the Zero Carbon Bill survives with its current targets, that is a fairly big deal.

The environment

Yes, it’s different from climate. Don’t let politicians or anyone else try to talk about recycling or plastic bag bans as climate solutions. They have little to do with it.

Anyway, Labour enacted a few chunky bits of environmental policy. It has helped that David Parker, one of the Labour government’s most effective and experienced legislators, was environment minister for the entire length of the government.

- Replaced the RMA with separate bills.

- Issued a policy statement on freshwater that restricts how farmers operate in several ways in a bid to clean up rivers.

- Ended subsidies for irrigation projects.

- The plastic bag ban.

- Reformed the Crown Minerals Act so that there is no longer a presumption that governments should promote the extraction of resources.

National has promised to replace Parker’s replacement of the RMA. That will likely take a few years.

National has also promised to repeal a lot of the freshwater regulations, but not quite all of them. Its website still says a full agricultural policy is on the way – I don’t think it emerged prior to the election. I’ve asked about the irrigation subsidies and not received a response.

The plastic bag ban is settled law and I doubt any future government would try to reverse it.

National opposed the Crown Minerals Act changes but from what I can see has not promised to repeal it.

Legacy survivability rating: 3/10. It’s hard to see a return to plastic bags or irrigation subsidies.

Total government legacy survivability rating: 4/10.

Look, the clock isn’t going back to 2017. As ever, big middle-class boosts like Best Start, the Winter Energy Payment, and fees-free education look fairly safe. Social policy strides don’t look to be in any danger of being removed. The state houses being built right now will keep being built, and the effects of the NPS-UD on urban form will ring out for decades to come.

But if you take a look across the ditch at Victoria, where a Labor government won re-election despite a very tough time through the pandemic, you can see the value of building actual concrete infrastructure that will last when your government is long gone. Dan Andrews’ government did something that might seem a bit boring – removing dozens of dangerous level crossings across rail lines. But voters appeared to love it and reward his party for it. There are plenty of policies people will remember from the last government, but a lot of it will be fairly easy to undo – because it exists on paper, not in concrete.