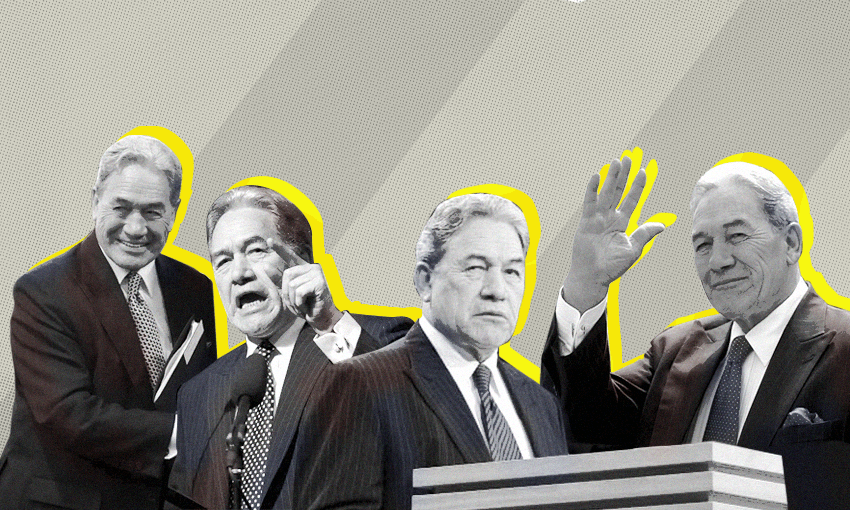

Christopher Luxon looks like he will have to call Winston Peters on October 15 to form a government. But which Winston will answer the phone?

Winston Peters has been booted from parliament on three separate occasions since he first entered in 1979. Every time it has changed him.

In 1981 his loss came just two years after he had fought a court battle to win his marginal seat as a National MP. After the court battle he had been mocked relentlessly and had largely toed the party line as a government backbencher. Never again would he be content with being a political nobody – one needs a reputation to survive in this game.

In 2008 he faced his first period in the wilderness since coming to national prominence and forming his own party in the early 1990s – a period when he temporarily was the most popular MP in the country, and then had acted as the kingmaker in both 1996 and 2005. He had been pushed out by a resurgent National Party whose leader John Key refused to entertain the idea of ringing him after the 2008 election – an unforgivable insult he would partially repay by bloodying the party in the Northland by-election.

And in 2020 he again found himself in the wilderness and with time to stew about a prime minister – one who he felt had kept him out of the loop on Te Tiriti issues and was now drunk with power. Labour would feel his wrath – he soon ruled them out as a potential coalition partner.

But really you don’t need to wait for a new election loss to see a new Peters. If you stay in a conversation with him long enough you can get a whole host of different Winstons. Christopher Luxon, it seems, will soon have the pleasure of several very long conversations with Peters, despite claiming a number of times at the second leaders’ debate that he “didn’t want to” work with him.

Here’s a guide to the different Winston’s he may get.

Winston the statesman

Everyone cracked up when the script of the They Are Us film leaked, featuring Peters reciting a Māori proverb to comfort Jacinda Ardern after the March 15 shooting.

They were right to, and Peters would never do that, but he absolutely can put all the hijinks away in a crisis and act with the dignity and deftness one would expect of our most experienced politician. After the March 15 terror attacks, Peters got out of the prime minister’s way and swallowed any objections to the firearms bans. During those chaotic early weeks of Covid-19, he gave New Zealanders overseas the clear message that they should travel home if possible and didn’t give any hint that there was anything but cabinet consensus around lockdowns.

And it isn’t only crises. Peters did a lot of work to get some warmth back into the US relationship in his first stint as foreign minister under Helen Clark. When he needs to be affable, wise, and careful with his words, he can be.

Winston the xenophobic race-baiter

Then there’s the Peters who joked that “two wongs don’t make a white,” who accused “two Asian immigrant reporters” of fake news, who called New Zealand “the last Asian colony,” who defended his deputy telling National MP Melissa Lee to “go back to Korea,” or a different deputy when he attacked a “flood” of Asian immigrants.

This is a man who has undoubtedly experienced some pretty strong racism himself through 78 years as a Māori man. But he has certainly been comfortable pushing the race button himself.

Winston the corruption watchdog

Peters made his political name in the 1980s as an attacker of corruption and secrecy, whether that be unproven allegations about ships in the Cook Strait or the very proven allegations about the Māori Loans affair. This came to a real crescendo with the “Winebox Affair” in the early 1990s – a sprawling set of allegations surrounding the bailout of BNZ that I’m not sure anyone but Peters himself can quite explain properly.

Winston the corruption watchdog watchdog

You would think all this dogged investigative work would make Peters an ally of our country’s top corruption watchdog the Serious Fraud Office. But when the SFO announced it was laying charges against two people following an investigation into the NZ First Foundation, Peters found himself instead attacking them as biased. Swings and roundabouts!

Winston the insult comic

Peters has a dexterity of language that can make his insults really sing. He once said Helen Clark was the “only politician in the Western world who can talk on foreign affairs with both feet in her mouth”. He called Gerry Brownlee an “illiterate woodwork teacher”. He’s called his potential governing partner David Seymour a cuck more times than I can count.

Winston the media critic

Most politicians attack the news media every now and then – if only to partake in our great national pastime – but Peters insults reporters with a reflexiveness and repetitiveness few can manage.

Sometimes this is just the way he gets through a tough interview, taking every single question as an affront and deciding to bog the interview down there instead of venture into any territory he would prefer not to touch. Sometimes it’s just a bit of throat-clearing on the way to delivering some other point – he once suggested I was working for the Act Party because I had quoted them in a story. This kind of stuff is usually done with a big grin on his face, with the implied promise that this is all a bit of fun and we can see each other at the parliamentary bar later to laugh about it.

At other times it gets much more vicious – like when he sues journalists or includes their ethnicities while attacking them.

Winston the historian

It is impossible to understand Peters without understanding the political era that shaped him – the neoliberal turn from 1984-1993, when huge parts of the state were privatised and the welfare system torn up. Indeed, I think the best way to understand Peters’ particular political oddities is to see him as someone who thinks things were pretty damn good before 1984, a view that endears him to the left economically and the right socially.

Peters has a remarkable ability to recall detail from his huge political career throughout this change. He will bring it up to make a point whenever possible, reminding journalists who weren’t even alive then of key political betrayals or victories, which he can almost always use to justify whatever point he is making that day. And the small moments of respect one can get from Peters usually come when you jump to the historical analogy before him.

He’s a man who remembers everything, as Luxon will soon find out.

Henry Cooke was chief political reporter at Stuff. He writes a newsletter about New Zealand politics called Museum Street.