At a recent wedding I was asked how Christchurch is doing now. It turns out that question is more difficult to answer than I thought.

On a warm autumn night in Melbourne, a nice man wearing a nice suit has two questions. The first is easy: Where do you live?

“Christchurch,” I tell him.

As he registers the name in his mind, the look on his face becomes pained and I wonder if I should have picked another city, one that did not invoke sadness in strangers, or a need to say something, anything, meaningful or profound. We are two strangers at a wedding trying to have a serious conversation in a room spilling out with wine, laughter, fairy lights and love.

The second question is predictable, but complicated.

“How – how is Christchurch now? I mean, after everything it has been through.”

Our little Christchurch. How was it, after everything?

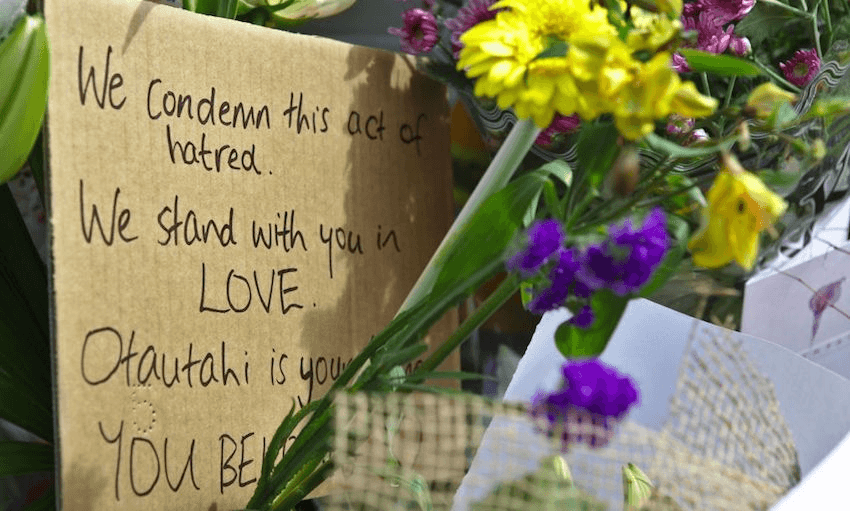

It was early April. Which is to say, it was just a few weeks after March 15 and flowers were still tied to mosque gates around the world. After everything had become a euphemism for terrorism.

“Oh. You know…” I say, drifting off. “It’s well, it’s been pretty hard.” But I don’t want to sound gloomy at a wedding, so I blurt out – “But Christchurch is a great city! It’s really beautiful!”

I can feel the desperation in my voice, exclamation marks filling the air. And then without thinking, as if it’s my responsibility to promote tourism, I say, “You should visit some time.”

I want to dance. I want to stuff my face with cake and champagne. I don’t want to – I can’t – talk about a city’s grief at a wedding.

Nor can I talk about all the things Christchurch has felt to so many of us at one time or another: frightening, exhausting, frustrating, depressing.

For the nice man standing in front of me, after everything meant March 15. But for many who call Christchurch home, after everything is a long list of heartache: earthquakes, fires, tsunami threats and terrorism.

Just when we thought we had been dealt ‘our share’ – whatever that means – we were dealt more. What words do you have for that?

How do I articulate over loud music and happy revellers that somehow we slipped from a random Thursday in March when we were doing sort of okay – the library was open, the streets were busier, the sun was peeking out – to a forever-remembered Friday when we were not okay?

There are a thousand narratives for our city. A thousand stories of where you were when the hills started burning, the ground started shaking, or the bullets started firing.

We have numbers – 50 – and revised numbers – 51 – and we have dates – February 22.

We have the day the fire turned.

We have locations: the red zone, two mosques, the Port Hills, Cashel Mall, Christchurch Hospital’s emergency room, the East. Thousands of cracked homes.

We have a thousand stories, which one do you want?

We have the complicated, the messy, the hard-to-explain: insurance battles, the panic of aftershocks, evacuations, a struggling rebuild, mental health impacts, school closures, lockdown, road works, the sound of sirens, a generation of children stressed.

And we have good stories too, of kindness and love.

Of volunteers, neighbours helping neighbours, brothers helping brothers. And food, endless food. Because you know, that when the heart aches, and the tears are welling up, and you’re desperate to offer something physical, tangible, real, Aunty Jean is already in the kitchen making a lasagna, or blueberry muffins to give away to someone in need. Maybe this time, she’s even Googling halal meat.

Nice man in a nice suit, are you asking if we are okay? Yes we are and no we’re not. It depends who you ask. But ask kindly, for some of our citizens carry a broken heart. You may not know that by looking at them.

Grief comes in many forms: displayed, delayed, and disguised. Some seek justice, others offer forgiveness, and some try to forget. Whether you believe in fate, faith, or blind randomness, disasters can spin in a way that feels utterly brutal and arbitrary.

Stories are peppered with what-ifs and should-haves. Minutes, seconds even, become crucial. He was late that day, so he didn’t enter that building. She never usually goes, but today she did.

We start our day oblivious of what is to come. We eat our toast, and down a coffee. Maybe we rush out the door, maybe we are lucky to kiss our dearest before we leave. We are not thinking of the fragility of life, the shock to the heart we are soon to get.

Nothing prepares us for that feeling of silently begging a loved one to answer their phone, to please, just send one text, tell me you are okay.

We are not ready to see our city, ourselves, become the story of international news. Our citizens photographed covered in blood, dust, and raw emotion. Unwittingly, and without consent, they become the face of our disaster, their images picked up by media here and abroad and replayed again and again.

We are not ready for what will unfold in the days, weeks, months, years to come, when the sirens have stopped wailing and the city has fallen quiet and we are left with our own reckoning.

After the earthquakes, big agencies stepped in to patch up our landscape and our hearts. EQC, ECAN, CERA, Ōtākaro Ltd, ChristchurchNZ, Christchurch Foundation, Regenerate Christchurch, Christchurch City Council.

It was hard to tell the difference between them all. Where did the remit of one agency end and another begin?

We were given a new lexicon, nearly a decade’s worth of Rs: Response. Resilience. Recovery. Regeneration. Rebuild. These R words defined policies and plans, strategies and funding categories but they left murky questions in their wake. Like, who decides if we are resilient?

Who determines when we are we recovered, physically, emotionally, collectively? Exactly when are we rebuilt?

For years we were told that Cantabrians – much like West Coasters following the Pike River Mine disaster – are resilient. And there is some truth to that, but it was a one-dimensional framing, an easy feel-good label that overshadowed what researchers began telling us – warning us – that actually for some of us, our mental health was creaking under the weight of everything.

All the while, mental health funding dried up like a prune.

Some call us a collection of winners and losers, but that leaves no room for nuance. Yes, some people do come out better off – financially, politically, and professionally. Tell me though, how do you know that they did not also suffer a loss?

Maybe they lost a loved one, or they saw their entire neighbourhood move away, or they have terrifying flashbacks in dark corners of their mind that they cannot shake, maybe they lost a relationship – worn down by ongoing stresses.

We do not know all the stories people carry within. And this pain, this ache, it does not end at the Waimakariri Bridge. Grief transcends borders.

From Kaiapoi to Japan, Auckland to Bangladesh, our tragedies have ricocheted around the world.

Recovery – be it from an earthquake or terrorism – involves complex decision making. From memorial design to the future of the Red Zone, Christchurch has had, and still has, many difficult decisions. Economics is pitted against emotions; speed versus deliberation; saving the old versus building back new and cheaper.

What’s best for the individual, the neighbourhood, the city, the country? What’s best for today, next year, in 50 years?

What’s good for business? What’s helps foster community? What’s good for public safety, accessibility, and inclusivity? Whose voices get heard? What can we afford? And who is going to pay?

Recovery costs – a lot. And where there’s money, millions of dollars, there’s room for disagreement. How money is split, between individuals, projects, neighbourhoods, and organisations, will never be 100% fair, because what is fair?

Occasionally someone, usually an outsider, publicly tells Christchurch to get over it, move on. As if all we ever needed was a good click of the fingers, to snap out of whatever it is that we are in.

We know that tragedy is not and cannot be our only narrative, but Christchurch is not static. We have always been living, navigating our way forward, sometimes blind, sometimes painfully slow.

We put up with roadworks and slept in cracked homes. We watched the hills burning, the smoke wafting over the city. We laid our flowers at your feet. We kept living, because what is the alternative?

So yes, some days Christchurch feels like cold houses, a broken city, and grey car parks, stuck in the clutches of disasters past. And some days it feels like blue sky, birdsong, and new cafes.

It’s the leaves turning gold, orange, red. The blossoms. The nor’west arch. It’s a city responding to tragedy with professionalism and compassion, and our communities responding with kindness. It’s Aunty Jean’s blueberry muffins.

There is tenderness in darkness. There is love. These are our stories. The good and the bad. The painful and the beautiful. A devastating, remarkable tapestry of stories.

As time marches on and the immediacy of our disasters and tragedies slip further into the past, the way in which we tell these stories may change. History will give way, allowing us to step back and see events placed into context and time.

But right now, at this moment, it’s just me and a stranger trying to have a serious conversation in a room spilling out with wine, laughter, fairy lights and love.

What can I possibly say to the nice man on the dance floor, at a time when flowers are still tied to mosque gates? How do we talk about Christchurch after everything?

To say nothing of our muddling confusion as we work out, once more, how to pick ourselves up again. To say nothing of our broken hearts. To say nothing of the things we cannot un-see.

But to say, Christchurch, for all her pain, for all the heartache she’s suffered, is ours. And we are hers.

You should visit some time.