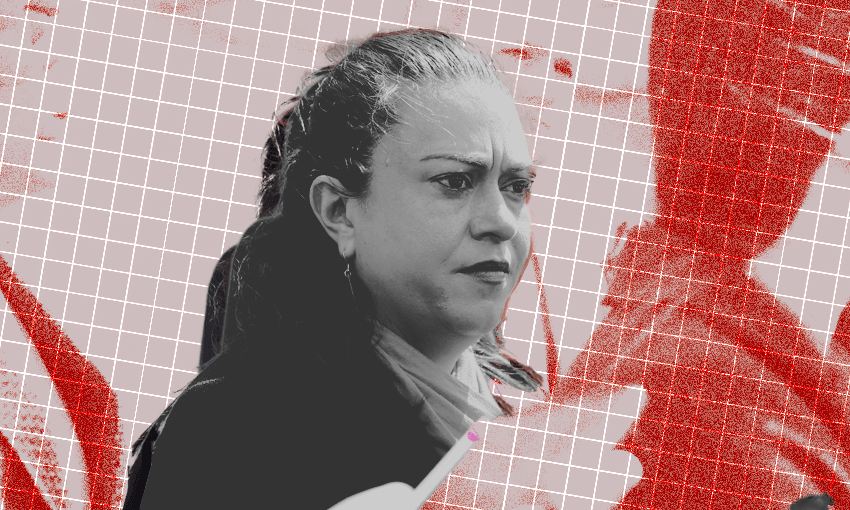

Today in the High Court, Crown lawyers will argue that the minister for children shouldn’t have to appear in front of the Waitangi Tribunal to answer questions about proposed changes to the Oranga Tamariki Act. Carwyn Jones explains.

The past week has seen two cabinet ministers publicly criticise the actions of the Waitangi Tribunal in its conduct of an ongoing inquiry. Shane Jones and David Seymour felt the tribunal had acted inappropriately by issuing a summons for the minister for children, Karen Chhour. Both Jones and Seymour also made slightly threatening comments towards the Waitangi Tribunal, with Jones stating that he was looking forward to reviewing the tribunal’s mandate and Seymour saying “Perhaps they should be wound up for their own good”. Te Hunga Rōia Māori (the Māori Law Society) considered that some of those comments were likely to breach ministers’ obligations under the Cabinet Manual. The prime minister has acknowledged the comments were “ill considered“.

So, what is all this fuss about?

The action that prompted the outbursts from Jones and Seymour was the Waitangi Tribunal’s decision to issue a summons for the minister of children, Karen Chhour. This means the tribunal will legally require Chhour to attend the tribunal’s hearing to be questioned as a witness who has information relevant to its inquiry.

The inquiry in question has been urgently convened to hear claims that the government’s proposal to repeal section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act is in breach of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. Section 7AA is a provision introduced in 2019 that sets out specific duties of the chief executive of Oranga Tamariki to “recognise and provide a practical commitment to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (te Tiriti o Waitangi)”. The claimants argue that the repeal will “cause harm to whānau and tamariki Māori, contributing further to the alienation and disconnection from culture that already exists for them in state systems and care”.

The Crown has indicated that it is likely that a bill to affect this repeal will be introduced in mid May 2024. The Waitangi Tribunal deputy chairperson found that grounds for an urgent inquiry to be held had been satisfied and appointed Māori Land Court judge Michael Doogan as the presiding officer of this inquiry on March 26.

On March 28, Judge Doogan noted that the lawyers representing the Crown had argued that the decision to repeal section 7AA was a political commitment in the coalition agreement and not the product of a policy process that officials have undertaken. For this reason, Doogan identified that the information central to the inquiry was likely to be held at a political rather than departmental level. Consequently, the tribunal directed a number of questions to the responsible minister, Chhour.

Among other things, the tribunal asked: What is the policy problem the repeal of section 7AA addresses? Could the policy objective have been advanced in a different way? Had the minister taken policy or legal advice on the proposed repeal? Had the Crown consulted with Māori about this? Doogan indicated that it would assist the tribunal’s inquiry if responses to its questions could be filed as a brief of evidence or an affidavit from the minister.

On April 5, the Crown advised the tribunal that it did not intend to call the minister for children as a witness as all relevant material was either covered by available cabinet papers or could be addressed by officials. The tribunal did not agree and took the view that evidence from the minister remained necessary to inform the tribunal of relevant information to its inquiry. It appears to be the minister rather than officials who have identified section 7AA as a problem, and it is, therefore, the minister who is able to speak to the reasons for that. In a direction issued on April 9, Doogan noted the tribunal’s authority to formally summons a witness to appear, but thought it would be preferable to invite the minister to reconsider her position and provide evidence voluntarily.

The lawyers representing the Crown subsequently confirmed they would not call the minister as a witness and nor did the minister intend to produce a written statement in response to the tribunal’s questions. The Crown argued that the tribunal should not formally require the minister to give evidence because it would be in breach of constitutional practice and principles.

The Waitangi Tribunal is a commission of inquiry under the Commissions of Inquiry Act 1908. Under its own legislation, the tribunal has the power to “issue summonses requiring the attendance of witnesses before the Tribunal or the production of documents”. All commissions of inquiry also have the power to “require any person to furnish, in a form approved by or acceptable to the commission, any information or particulars that may be required by it”. Though it very rarely invokes these powers, it seems pretty clear the tribunal has the legal authority to require the minister to provide relevant information. Doogan duly issued a summons for the minister to give evidence.

However, Doogan also acknowledged the Crown’s arguments about constitutional principle and practice. Doogan, therefore, set the date for the summons as April 26 to allow time for the Crown to test these issues in the High Court (in a hearing scheduled to take place today), and even indicated that if the High Court proceedings could not be completed by April 26, he would adjust the date of the summons accordingly. Far from being evidence of a tribunal running amok and overstepping its authority, these proceedings appear to be the very model of careful and reasonable decision-making, with due regard and deference to the constitutional relationships at play.

In fact, it may well be Shane Jones and David Seymour who are the ones who are transgressing the bounds of constitutional propriety. The Cabinet Manual sets out the duties and obligations of ministers and includes a number of provisions that are intended to uphold the independence of our courts. These include a requirement that ministers must “exercise judgment before commenting on matters before the courts or judicial decisions” and that “ministers should not express any views that are likely to be publicised if they could be regarded as reflecting adversely on the impartiality, personal views, or ability of any judge”.

Although the Waitangi Tribunal is a commission of inquiry rather than a court, it does carry out a quasi-judicial function and its chairperson, deputy chairperson and the presiding officer in this particular inquiry are all serving judges. It is not difficult to see why the same principles that apply to protect the independence of the courts might also apply in relation to a tribunal that inquires into wrongs alleged to have been committed by the Crown. As Te Hunga Rōia (the Māori Law Society) has noted, comments such as those by Shane Jones undermine the tribunal in particular and the integrity of our judiciary more broadly.