How New Zealand startup myReflection is making bespoke, affordable, mass-produced breast prostheses using 3D printing.

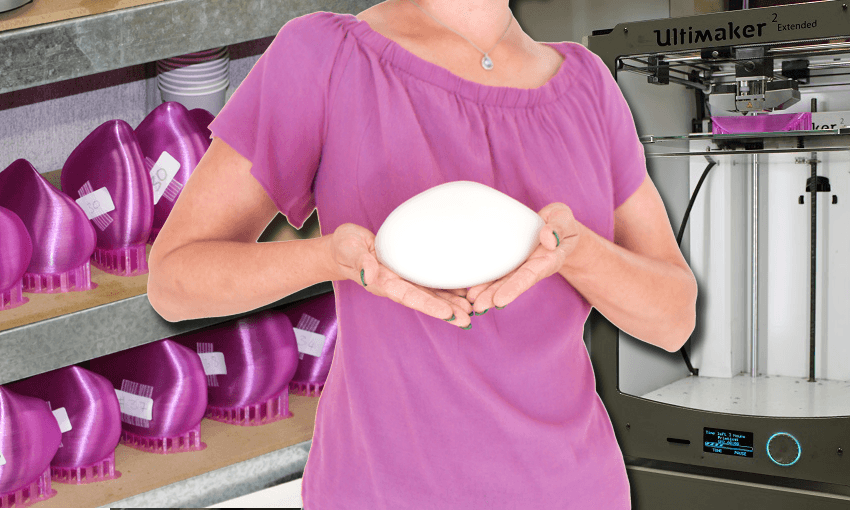

In a garage on Auckland’s Te Atatu Peninsula, dozens of 3D printers work mechanically away to a rhythmic, whirring hum. On a nearby table sits an array of white “blobs” – some large, some small, some more spherical than others. They’re smooth to touch and light to hold; elastic and supple, like a tightly squeezed bag of water.

But there’s no liquid in these blobs, and they’re not just “blobs” either – they’re breast prostheses, each one custom-fit for women who’ve had mastectomies to treat breast cancer, which affects more than 3000 women in New Zealand every year.

One of these women is Fay Cobbett, who underwent a mastectomy (the surgical removal of the breast) back in 2015 at just 35 years old. After her surgery, she began using a generic prosthesis but found it incredibly uncomfortable and difficult to wear. “I just went flat-chested. I gave up wearing it,” Cobbett recalls, four years on from her diagnosis. The prosthesis, essentially a “big lump of silicone” held tentatively in place by a special mastectomy bra, made her feel self-conscious, awkward, attracting furtive glances from passersby, something her husband, Tim Carr, noticed as well.

“I picked up the comments. I picked up the little flicks of eyes from people looking at Fay and noticing her breast didn’t quite sit right or wasn’t quite symmetrical, and it hurt my heart,” says Carr, who decided to look for ways to help. As the owner of a 3D-printing business called Mindkits, he looked to technology for a solution, and with the help of his colleague Jason Barnett, myReflection was born.

Made from a specially designed inner “core” and an ISO-certified outer silicone, the breast prostheses produced by myReflection are more comfortable and more affordable than the ones that currently dominate the market, the company says. Uniquely, the product is both bespoke and mass-produced – bespoke as each prosthesis is custom fit following a 3D torso scan by a fitting consultant, and mass-produced as a 3D printer then takes that data to produce the physical mould.

“What we’re doing is hand-crafted prostheses en masse,” says Carr. “Humans are doing what humans should do, which is the stuff that’s too complex for robots, and robots are doing what robots should do, which is the [physical, repetitive] work.”

Furthermore, unlike most prostheses, there’s no need for a special mastectomy bra – just a well-fitted regular bra will do – and with the $613 subsidised by the government for women who’ve undergone partial or full mastectomies, myReflection will cover four prostheses over a four-year period rather than the usual one (Cobbett says a traditional prosthesis usually costs around $450). Not only does this provide the opportunity for a new prosthesis to account for physical fluctuations like weight loss and weight gain, which become common during cancer treatments, but it also gives people a sense of assurance that if they break or lose their prosthesis before their next four-year period, they’ll have plenty more to back them up.

“Traditional prostheses don’t tend to last that long, so there’s a real concern when you start to see your generic prosthesis slowly deteriorate, knowing you might have to buy the next one out of your own pocket,” says Barnett. “The material we use for our prostheses is very stable, elastic and tear-resistant so it can last the four years, but it depends on the user. Ultimately, each prosthesis is made to be usable and loseable, and it’s about giving these women a sense of confidence.”

There are many reasons why having a prosthesis is so important to these women. For one, it helps preserve physical traits like posture and balance, but it also helps restore one’s self-esteem and self-image as a woman following the loss of one or both breasts.

“These women have been through hell: they’ve gone through the absolute trauma of having cancer, having a breast chopped off, and having to see someone different in their reflection,” says Carr. “On top of all that, they have to deal with a prosthesis that’s, arguably, barely functioning.”

“It’s not just a blob. Everyone thinks that about a prosthesis, but it’s not – it’s a sense of completion.”

Since launching in February earlier this year, myReflection has already sent out hundreds of prostheses to women across New Zealand. So far, the business has been entirely self-funded and financially, Carr says it’s doing well (“We’re in a slightly unique position where, unfortunately, we have almost unlimited customers needing breast prostheses”). He says the business has no plans to seek out further investment or funding, preferring to instead focus on making its current operations as efficient as possible.

“I have an obsession with efficiency and systems. That’s my thing. Our goal right now is to reach 320 units in a month, which is utterly doable with what we’ve got. That would make us an extremely efficient business.” After all, 320 units sold for $613 each (approximately $196,000) is a pretty significant earning for a self-funded startup operating out of a Te Atatu garage.

With that said, Carr already has some pretty clear plans for moving the business forward.

“Currently we use 3D-scanning consultants who are trained, but in the long term, I want to be able to send out a scanning pack around the world to anyone who has an iPhone. The face scanner on the iPhone (which is used for Face ID) is actually a phenomenal 3D scanner,” says Carr, who already has a working prototype of how the set-up would work.

Furthermore, Carr sees further applications for his technology beyond just breast prostheses: custom sockets for limb prostheses, slimline masks for people suffering from sleep apnoea, and providing 3D-printed solutions for those in the trans community.

“I think we’re upsetting some of the people in the [prosthetics] industry who’ve traditionally been doing it. They tend to be 70-plus years old, peddling traditional products, when suddenly, [a company like ours] comes along that applies technology to everything to do things faster and better.”

“It’s a bit disruptive… and what an amazing thing to come out of something so traumatic.”