For only the 7th time in New Zealand history, the Office of Film & Literature Classification has banned a video game: the highly sexualised Japanese game Gal*Gun. This week two of our writers examine and respond to the decision to ban the game in question and we ask the Chief Censor to expand and explain his office’s ruling. Here, law degree-brandishing gamer Eugenia Woo looks at how our censorship laws were applied in this case.

From our Gaming editor José Barbosa: Censorship’s a funny old game; it’s mostly all about viewpoints and there are obvious paradoxes and contradictions in having censorship in an operating democracy. That and questions around where society draws the line and how new technology pushes, and sometimes mocks, the very idea of a line contributes to a deeply interesting area for discussion, which we’ll be having all this week. After reading Eugenia’s thoughts below, click through to Matthew Codd’s reasoned defence and my interview with Andrew Jack, the Chief Censor.

*

Disclaimer: The writer does not in any way endorse the behaviour in games like Gal*Gun.

So, the OFLC (Office of Film and Literature Classification Office) has done it again. They’ve banned another game. Since Manhunt was banned in 2003, New Zealand has banned a further six games, and Gal*Gun: Double Peace is the latest to be classified as “objectionable” – a term that makes me think of the sort of mild reaction someone’d have to a cafe fucking up their brunch order. However it’s a bit more serious than that: Gal*Gun is illegal to sell, own, possess, or import.

Now, plenty of things are illegal. That’s not a hard concept to grasp, but possessing a video game will probably seem kinda trivial to most of us in comparison to the things that we’d conventionally think of as Shit Not To Do e.g. punching someone, breaking into their house, setting a bunch of stuff on fire.

I didn’t want to make a snap judgement, however, so I decided to read the entire OFLC decision (mercifully short compared to what I’d been subjected to at law school) to see how the concerns listed matched up to the actual game. Of course, it goes without saying that I wasn’t able to physically play it, but there was plenty of footage on YouTube, and I had a mate over the ditch who sent me screenshots and tried to let me watch him play it via videolink. Now, there was quite a bit of jargon in the OFLC decision, so I’ll keep it simple.

For anyone not familiar with the musty (yet lovable) document that is our Bill of Rights, section 14 says that everyone in New Zealand has the “right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and opinions of any kind in any form.” Theoretically, that right should be extended to us, the consumers of videogames in general. However, it isn’t absolute – it’s subject to limitations in law that can be “reasonably justified in a democratic society.” One such limitation is the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act (FVPC) aka the Act that allows the OFLC to restrict or ban any publication it wants as long as it meets the relevant criteria. For a game to be banned, it’s gotta be objectionable, which is defined in the OFLC as:

“A publication that describes, depicts, expresses, or otherwise deals with matters such as sex, horror, crime, cruelty, or violence in such a manner that the availability of the publication is likely to be injurious to public good”

The decision on Gal*Gun focuses on two particular aspects of the quote above – sex and crime. Now, for those who are unfamiliar, Gal*Gun is a game that starts off with you getting shot by Cupid’s arrows and suddenly every girl you know thinks you’re fine as hell. It sounds alright, yeah? Who’d complain about a game that hinges on a bunch of attractive people in your area basically swiping right on you before it was cool?

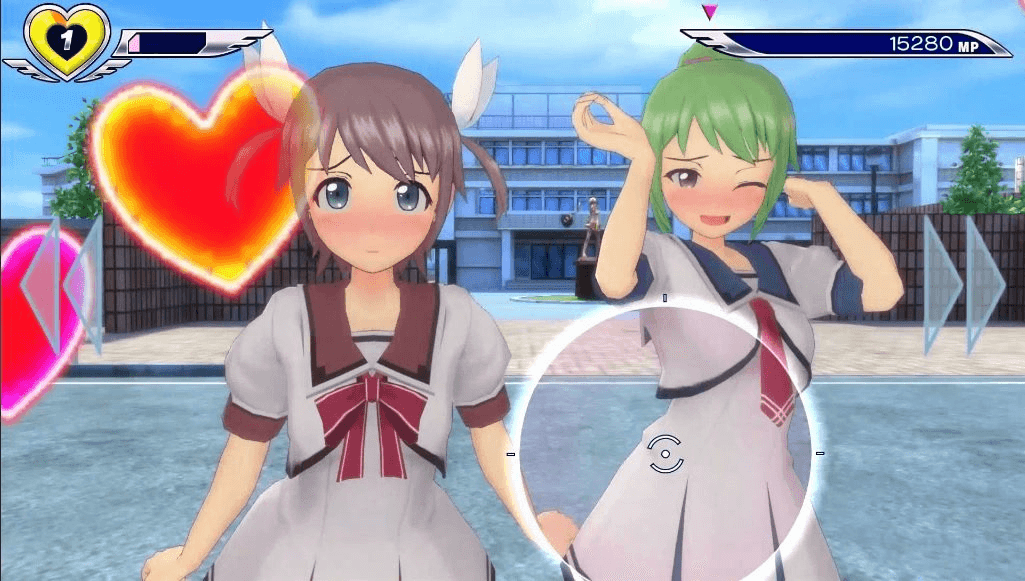

Well, life comes at you fast. In this case, that was about 10 minutes into the game where it went from cute to what I’d like to think is objectively a bit creepy. First, some girls wanted me to date them. Weird, but cool. Then, they started blushing and lightly hitting me whilst proclaiming their love for me. A bit less cool. Then, the tutorial told me to scan their bodies with a magical pheromone gun (turning their high school outfits transparent in the process) and to shoot them in places like the hips, breasts, and face. Hmm.

If everything about my description sounded off to you, then congratulations! You could probably work for the Classifications Office: one of the things that they didn’t like about Gal*Gun was the sexual undertone that props up the incredibly flimsy narrative, particularly because of the ambiguous age of the girls involved. They’re in high school uniforms but in my opinion, the anime-style graphics made them look much younger than Year 12.

Taking a direct textual interpretation of section 3(1A) of the FVPC Act, “matters of sex” that make a game objectionable includes visual images of young people who are nude/ semi-nude in the publication that can be interpreted as sexual. Following that train of thought, it isn’t hard to see why Gal*Gun was given the chop. However, that was far from the only concern of the OFLC in their judgement. In fact, it was really just an ancillary one in the scheme of things.

As previously established, the Bill of Rights Act (BORA) is important. Super important. And yes, while freedom of expression is a right that can have justifiable limits imposed on it, the courts have tried to take an approach that doesn’t take a dump on said right. What this means is that in most cases where legislation appears to impose a limit on a particular freedom in the BORA, courts have chosen to interpret and give meaning to that legislation in a way that interferes as little as possible with the freedom that it seeks to restrict.

The OFLC relied on the case of Moonen v Film and Literature Board of Review (Moonen I), where our Court of Appeal decided that the pure depiction of an activity that falls under the definition of “objectionable” isn’t enough to get a game banned. A game would have to “support or promote” that objectionable activity, or encourage it, to earn the banhammer.

We already know that the game is about getting pheromones into young girls. Each girl that you encounter is also shown via the game’s UI to have weak spots, many of which are places that are arguably totally unacceptable to grab, especially considering the fact that your player character is a total stranger to these girls and that they’re not in their right mind to consent because they’re drugged, in a way, by those pheromones.

There’s also the usual, conveniently-placed but utterly unnecessary tentacle monsters that seem to be part and parcel of hentai these days, and there’s no real explanation for what’s going on there. I don’t know about you, but if we’re talking about whether or not the game supports and encourages the sexualisation and coercion of young persons, I’m gonna say yeah, it definitely does.

So far, we appear to be two for two in terms of the concerns that the OFLC has about the game being met. However, the real kicker in Gal*Gun for the Chief Censor was section 3(2)(b) of the FVPC Act: “the use of violence or coercion to compel any person to participate in, or submit to, sexual conduct”. I watched a good 10 hours of footage of the game covering various points in the plot, so I might have missed more elements that explicitly pertain to the use of violence and coercion, but I do admit that it’s addressed, and it left a bit of a bad taste in my mouth.

The example given in the OFLC judgement is when you have to decide between two NPCs (non-player characters) to be your girlfriend. Not satisfied with just one, you use your pheromone shots to get both the girls to have a threesome with you. There’s no nice way to interpret that. Adding coercion to dubious consent to the sexualisation of possible minors leaves us with a very potent brew of Irresponsibly Bad Attitudes to Sex, and that’s me understating it a fair bit. The more time I spent with the game, the more the OFLC’s concerns stood out to me and seemed well-supported.

However, that doesn’t mean that I agree with the decision to ban the game. I can find something distasteful and not think that everyone in the country should be unable to access it. On top of that, I can find something distasteful and also not think that it’s totally irredeemable and anti-fun. Truth be told, I think Gal*Gun is super tongue-in-cheek and some parts of it are entertaining. It plays and sounds more like a parody of an eroge (Japanese pornographic game) than anything, and while it uses guns as part of the game’s combat, it’s less Grand Theft Auto and more like a raygun of moe.

I’ve already made my anti-censorship stance clear, but I’m not purely against the ban just because I don’t think publications should be censored full stop. Much like the OFLC, I’ve got my own justifications, and they might be polarising.

First off, I’m going to refer to the swathe of games that New Zealand hasn’t censored. Here, let’s go with good ol’ Grand Theft Auto V, God of War, and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. Why is the Classification Office ignoring us torturing people, gorily ripping their spines out, and letting us decide whether or not we’re able to shoot up an airport of civilians? What makes that sort of behaviour okay, and not the cartoon antics in Gal*Gun? There’s the age-old argument that people who play violent or “objectionable” games are going to end up re-enacting them in real life.

In my opinion, a few outliers don’t make this argument substantial. Furthermore, judging by the reactions of various review boards to the airport scene in Modern Warfare 2, it was clear that while there was incredible violence, what was being considered was the purpose or the tone that the scene set. Some people, including the producers of the game, asserted that the point of the scene being that intense and hard to stomach was so that it would make players feel something visceral. While people hemmed and hawed about that interpretation, it wasn’t banned in New Zealand, and it was merely given a high restricted rating in Australia.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8W04xuzUMz8

My point here is that there was the chance for consumers and game studios to have a productive conversation with the relevant censorship bodies about the offensive content in a game and to justify it. I’d even argue that the only reason why Modern Warfare 2 was given so much press and consideration is because that the main concern was violence, and not sex.

There’s a trend of ham-handed treatment of sex in videogames, both in terms of oversexualisation and kneejerk reactions to eliminate sexual content. It’s easy to point at something and recognise that it’s offensive and objectionable, but if there’s no apparent consistency across the board as to what gets banned by the OFLC then what’s the point? Game studios aren’t incentivised to listen to consumer or censorship concerns when there’s arguably no nuance applied to deciding whether or not controversial material is banned. Taking a game out of the public eye makes it hard to build meaningful dialogue around the issues that it might promote or depict, and we know that making things taboo only increases the fascination that they inspire within those who would fight to get their hands on the content no matter what.

Sure, Gal*Gun makes me feel a little gross inside, but as to whether I think that’s a justified limitation on the public’s right to freedom of expression in New Zealand? The answer is no. I’m not that selfish.

The Spinoff’s gaming content is brought to you with the help of Bigpipe Broadband.