The veteran scribe talks to Grant Smithies about glam’s ‘gleeful celebration of falsehood, façade and artifice’ – and casts judgement on New Zealand’s own platform-booted glam heroes, Space Waltz.

It’s about the size of three bricks, side by side. Maybe four. If you accidentally knocked it off your bedside table, it could kill your passing cat.

A giant slab of learned chin-stroking about glam rock, Shock and Awe (Faber, RRP $55) by UK journalist Simon Reynolds is a mother of a thing,

704 pages long.

“Yes,” offers the brevity-dodging writer down the line from New York. “It’s a bloody big book. The physical copies just arrived over here, and you could use it as a weapon, or do your back in if you picked it up without having a stretch first!”

An Oxford-educated Londoner, Reynolds started as a staffer on weekly rock rag Melody Maker in the 1980s, and these days splits his time between London and New York, pimping his prose to The Guardian, Village Voice, Spin, The Wire, Rolling Stone, The New York Times. He’s prolific as a journalist, his tone always jammed midway between scrupulous scholar and breathless fan-boy, but his reputation rests on three key books, all of which come highly recommended.

Energy Flash (1998) took apart electronic music, rave culture and assorted other drug-fucked bleepery from an eloquent clubber’s point of view. Rip It Up and Start Again (2005) considered the flowering of post-punk adventurousness in the late 70s/ early 80s, with all manner of insightful blather on kick-arse bands such as Joy Division, Television, Gang of Four, Pere Ubu, PiL, Talking Heads and The Fall.

And 2011’s Retromania waxed long and brainy on the rapid-cycling nostalgia-fest that is modern pop culture, bemoaning our “unhealthy fixation on the bygone” as evidenced by everything from endless band reunion tours, movie remakes and live performances of classic albums to “the strange and melancholy world of retro porn”.

And now, Reynolds sets his sights on the bygone himself with a book on glam. Why, exactly?

“There hadn’t been a really in-depth book on glam, just a few shorter or more academic ones, and books on key figures like Roxy Music and Bowie. It struck me that this idea of gender-bending, decadence and theatrical rock occurred pretty much simultaneously to a bunch of different people, and I wanted to pull them all together and look at what provided the cultural backdrop to what they did. I wanted to tell deeper stories on the main characters and rescue some of the more forgotten figures.”

Glam is Dead, so Fuck Me From Behind. But surely all this platform-heel teetering, mascara-caked, faux-bisexual palaver is old hat now.

It was just a gaudy little stopover between bubblegum pop and 70s hard rock, wasn’t it? Or perhaps a reinvigorating tea and biscuit break on the long journey from vaudeville to hair metal. Why write about it now, and at such mad length? You might be excused for thinking an overview of glam could have been a very short book.

“I was a bit shocked at how chunky this book was when it arrived, I’ll admit that,” says the author. “But I think the subject deserves it, and it’s quite a fast read because the key people are such strange and compelling characters, and the social and cultural landscape of that time was fascinating. When their images appeared in the Melody Maker or on Top of the Pops, they were alien and exquisite, and consciously courted publicity through shock tactics.”

Though short-lived, Glam was a Big Deal, he says. The glittery silliness of the look skewered the earnestness and pomposity of late 60s folk and prog, and its homoeroticism was a deliberate undermining of more macho music forms that had come before.

After beards, denim and dreary “authenticity”, it was gleeful celebration of falsehood, façade, artifice. Glam was “hysterical in both senses”, as Reynolds puts it – both hilarious and emotionally overwrought. It was brash and gaudy and pervy and fun, and its roots ran deep.

“Some of the concepts glam artists recycled could be traced back to people like Oscar Wilde and dandyism. The next frontier for music was this taboo exploration of bisexuality or androgyny. It partly came out of the long-haired male look of the hippy era, but stripped away all the ‘back to nature’ stuff and gloried in all things artificial, freaky, trashy and plastic. I mean, it doesn’t take much for an Englishman to get into drag, but usually that’s for comedic effect, rather than the more sexualised, forbidden, bohemian thing glam tapped into. Mostly these musicians were straight blokes, enjoying the game of confusion and ambiguity. Either that, or adventurous art students.”

Reynolds’ book is particularly good at capturing the raw excitement of the era, giving a glimpse of what a gobsmacking brainfuck glam was when it first hit the spotlight. His admiration leaps off the page as he testifies to the audacity of both bands and fans – their willingness to look like extraterrestrial Greta Garbos in tough little towns where this might earn them a kicking, their conspicuous sexualised playfulness in a culture renowned for emotional reserve, the insistence of many key participants on conjuring up more compelling backstories for themselves.

Marc Bolan’s mum ran a market stall and his dad drove a lorry, but right from his teens, the ambitious wee narcissist was in revolt against the sensible, the staid, the ordinary. After reading a library book on Regency era dandy Beau Brummell, Bolan took to changing his clothes four times per day, adopted a faux-posh accent and claimed to have special powers, having studied magic while living in a forest, up a tree, with a French sorcerer.

Bolan, Bowie and Roxy Music were surely the sexiest of the early glam acts, but you have to admire the dedication of some of the others who didn’t let a comparative lack of talent, good looks or charisma prevent them from joining the party, giving their music an extra kick up the charts by making themselves over as a diverting visual cartoon.

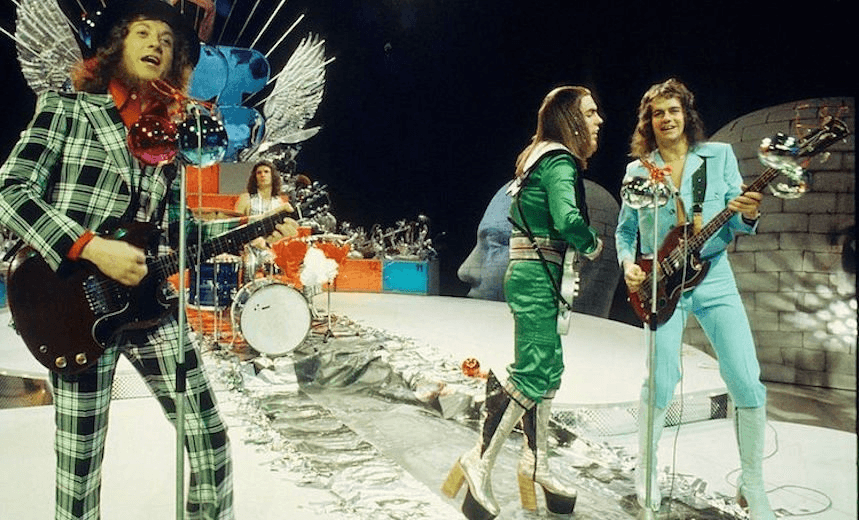

Sounding like the unholy love-children of The Archies and The Who, The Sweet married long lustrous lady-hair with thigh-high silver space boots and Formula One jumpsuits.

Wizzard’s bass player got about in roller skates, angel wings and oh-so-English cricket pads, while lead singer Roy Wood favoured face-painted stars, a rainbow-died afro, enormous tweed flares and purple patchwork cape.

And Slade, who hailed from unglamorous working class burgh of Wolverhampton, looked like brickies and railway workers who’d shoplifted their stage wardrobe from a Glasgow womenswear store.

All of which is to be celebrated. “Yes, I think so. And you have to admire the fact that embracing glam was risky. Glam fans would often run a gauntlet of boots and fists when they went to concerts, just as punk fans did a few years later. You were very visible to young mainstream thugs who saw what you were doing as extremely confronting and provocative. There are loads of stories of glam fans wearing straight clothes out of the house then creeping into alleyways or pub toilets to change their clothes and smear on glitter just before the shows.”

The best of the early glam acts had two main qualities in common, reckons Reynolds. They were exhibitionists and they lied through their teeth.

“A lot of these people were very fast and loose with the truth. It was interesting to me how we enjoy that in a pop star, but hate it in our friends, or a mechanic or plumber. But a lot of our biggest pop stars were very good at lying, and I was touched by their very open lack of integrity. Bowie and Marc Bolan in particular just kept changing all the time, and their main impetus was simply to be famous. They’d both started out playing acoustic guitars and singing folk songs to stoned hippies, but they had no desire to be stuck there, in a fug of incense and patchouli. They wanted to be stars, with people screaming at them, so they became their true selves, which was a couple of raging egomaniacs. Bowie in particular was the ultimate early adopter. He always wanted to jump on a new thing first, and then move on once too many other people caught up. First in, first out – that’s the hipster’s creed.”

Reynolds sees glam precursors in Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, and hears echoes in punk, new wave and hip hop.

“Most of the punks in Britain were huge glam fans, and you can hear it in their music and see it in the strong fashion element of punk, which just went for stylised ugliness instead of the stylised prettiness of glam. The impulse was the same – to kick the passers-by in the eyes. And people like Kanye and Drake make records focussing on their own fame and notoriety and the act of creating their own image, in a way that’s not that different from what Bowie did.”

A closing section called “Aftershocks” casts the net wider still, rounding up many others Reynolds believes were not just touched by the manicured hand of glam, but given a lengthy massage – from Grace Jones to Gaga, Morrissey to Minaj, Suede to Beyonce, Prince to Kate freakin’ Bush.

But there’s one glaring omission. If a man’s going to allow himself 704 pages to bang on about glam, there’s surely no excuse for leaving out Aotearoa’s sole great contribution to the art-form: Space Waltz.

Led by our own indigenous Bowie clone Alistair Riddell alongside future members of Split Enz and The Angels, this was by far the greatest local band to ever don platform boots and unreasonable blouses made from their mum’s curtains. The band’s pouting, stomping 1974 single Out On The Street shot directly to Number One on our pop charts, propelled upwards by hordes of amorphously horny teens who bought the single the day after they saw the song on telly.

I sent Reynolds a YouTube link. What did he reckon?

“It’s a good song, and the band really had something, especially that front man. I like his oh-so-English accent – very Tim Curry. As you say, there’s some serious Bowie damage there, and the guitarist has got Mick Ronson down pat, too.”

Inexcusable Space Waltz oversight aside, Shock And Awe rips. Reynolds’ enthusiasm is infectious, and his Mensa hepcat prose style has sufficient energy and wit to hold your attention during most- though not all- of his diversionary riffs and long-bow theorising.

His research has uncovered telling anecdotes for Africa, too, allowing fresh insights into the private lives, motivations and sometimes surprisingly twisted psyches of many key participants.

Best of all, he makes you want to dig these records from your shelves, or trawl around YouTube, to experience the shock of the new all over again.

Did the book need to be quite so big? Perhaps not. Like myself after three pints, I suspect Reynolds likes the sound of his own voice a little too much.

It’s also possible that such verbosity is a professional strategy of sorts. Also known as “rapid dominance”, “Shock and Awe” was originally a military tactic where spectacular displays of force were used to overwhelm the battlefield and paralyze the enemy’s will to fight.

Reynolds does this, too. If there’s a musical territory he’s interested in, he goes in hard and heavy and tries to own it. Whether it’s rave culture or post-punk, pop nostalgia or house music, hip hop or glam rock, he fires out big, meaty tomes at regular intervals so these areas feel comprehensibly claimed.

He puts his flag in the ground, and says “mine!”, and other writers have no option but to walk away and write about something else.

Reynolds’ tendency to take such an exhaustive, scholarly, self-consciously serious approach to the cheap thrills of pop music has led some reviewers to take the piss out of the guy, and such critics will find fresh ammunition in this book.

Unsurprisingly, Reynolds hauls in many of his usual chums to help with the heavy lifting on the long march through these 704 pages: Italian futurists, French symbolists, Nietzsche, Roland Barthes, assorted key thinkers on semiotics, Marxism, political science and cultural history.

But he gets closer to the sexually aroused, melodrama-heavy spirit of glam when he quotes from more humble sources, as with these brief, quivering lines from a letter 15 year old T-Rex fan Noelle Parr sent to Melody Maker after seeing Marc Bolan live on stage: “His body actually ripples. It’s too much. He pumps feeling into you. You just let yourself go.”

“Yeah, you’re right. Some people really hate all the theory I put in my books. They’ll get on Amazon and complain about my ‘tedious turgid verbiage’ and accuse me of over-analysing every little thing, and I think, sure, some of the books I wrote early on were pretty clumsy in their use of big chunks of theory. But I wasn’t doing it to show off. I’m a big fan of art theory, philosophy and critical writing, and I wanted to convey my enthusiasm for the ways music could be understood though these lenses. I wasn’t desperately trying to validate rock music by dragging in all these bespectacled European heavyweights; it was just that their theories had pertinent parallels with what the music was doing and what it might be telling us about our wider culture.”

Yes. Fair enough. But as Reynolds well knows from his rave bunny past, music is also big fun to listen to when you’re off your tits and it’s really loud and you’re not really thinking about anything beyond “FUUUUUCK! “This is SO GREAT!”

“That’s true. Sometimes too much analysis can obscure the pure pleasure of music. But pop music has had some profound effects on our culture. It means a lot to some people, and I’m one of them. I like to incorporate some theory without losing sight of the raw force of music, and the way it works you up, emotionally and physically. What I’ve tried to do in all my books is to mesh the cerebral interpretive stuff with more evocative language where I testify about the power of music to just, you know… melt your brain.”