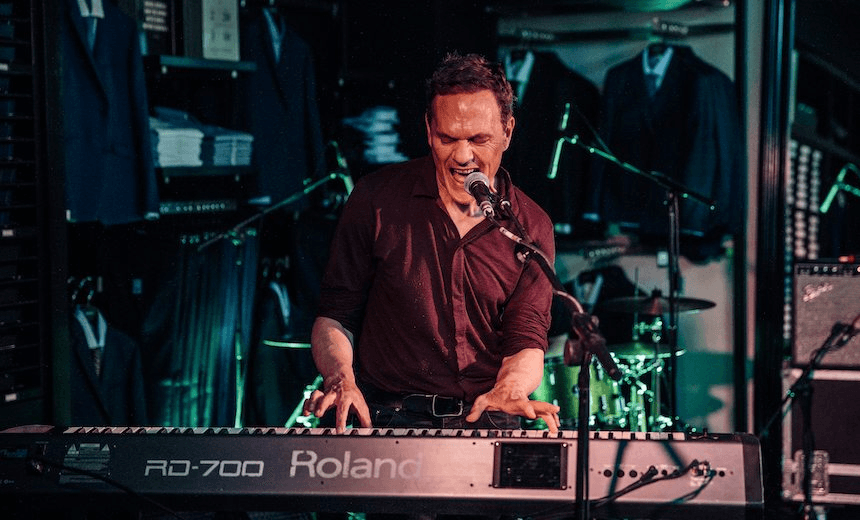

The long journey that turned Shayne Carter, one of New Zealand’s great guitar heroes, into a classical piano music fan.

Like most people under 70, I’d always found classical music a bit of a bore, a wing of the museum I hadn’t found the key for, the property of blue rinses bussed in from the rest home, the turf of snobs and academics.

It conjured up images of a camp Mozart skipping about pointlessly in his powdered wig or of unsexy orchestras conducted by gloomy Eastern Europeans, the audience out front stiff with attention, or maybe rigor mortis, nodding off as some pile of notes wafted interminably around them.

I could make neither heads nor tails of it. I’d liked a bit of Satie but only because he reminded me of Brian Eno. But I couldn’t get a handle on Handel; Schubert was all bubble and fizz. The business of Beethoven fell on deaf ears. Classical music seemed hopelessly impenetrable to a card-carrying rocker like me.

All this changed, though, when I decided to write my most recent album on piano. It was an instrument I’d never played before — 88 keys of mystery in blurry black and white. I can play guitar pretty much in my sleep, but I figured writing on a totally new instrument, where I had no idea where my hand went next, would, at the very least, produce a new strain of song.

It was a possibly foolhardy decision that led to many months of teeth-gnashing as I laboured about the keys, but it was also a deliberate step into the unknown. After three decades of dealing with tunes it was good to shift the posts.

I thought I should learn something about the piano before I began my album. I knew the classical people had a head-start of about three hundred years with that, and had fully explored the sonorities and possibilities of the instrument.

A dip into the solo piano repertoire, the popular pieces still played in concert halls today, would probably save me an awful lot of time. Beethoven. Debussy, Chopin, Schubert. One instrument, one melody line, no orchestras or massed choirs to muddy things up — the directness of piano music might also help me make sense of the remote classical world.

I stood like a tourist at the foot of Everest. The tower of music loomed forebodingly before me. I began with baby steps, playing piano records in the background as I went about the day, letting the tunes seep in by osmosis, not getting too close in case I scared myself off.

Over the next few weeks the slow-drip method started to take and the music began to fall into place. Melodies untangled. Their logic unfurled. Basically, I listened, and listened again, until the music made sense. As an unschooled musician, I had no charts or technical knowledge to fall back on, but I liked how I absorbed these sounds in an instinctive way. Music is a visceral and spiritual experience. Its magic, the unspoken experience it articulates, can’t be explained in a lab.

Classical music moved in strange and unfamiliar ways. Pieces would constantly morph and travel through new vistas and it was your job as the listener to pay attention and keep up. There were none of the blues strains that have shaped rock, R&B and almost all of today’s popular music. You could say classical music was the whitest music in the world. It lacked the familiar pop rock tropes of returning to the chorus and a comfy home base.

Still, I already knew, after years of grappling with the more abstract corners of rock, that the best listens often don’t come easy. Many of my favourite records have been ones I haven’t even particularly liked at first but there’d always be something intriguing about them that would draw me back again and again until they eventually revealed themselves. The end effect was deeper and lasted longer than the cheaper, more immediate pop thrill. What you put in was what you got out.

I found this certainly to be true with composers like Bach who I initially didn’t get at all. His music seemed mathematical and clinical. I couldn’t find any spaces to put myself in. Finally, though, I discovered a record of his cantatas — church songs he dutifully rolled out every week as part of his job as a working stiff in Northern Germany — sung by the late American mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson.

Hunt Lieberson’s singing and Bach’s mesmeric tunes completely won me over. The cantatas had a haunting quality devoid of any syrup or sentimentality and odd, angular bass lines like the ones Brian Wilson used on Pet Sounds, except 30 times better. This led me to more of Bach’s wonderful works, like his violin partitas, cello suites and keyboard concertos. Along with Beethoven, Bach is probably the greatest composer of all.

Beethoven, too, never gave himself up cheaply. I spent months listening to his late string quartets, which on first appearance seemed drawn out, aimless and meandering, until gradually I understood that this was music that existed on a plane entirely separate and above the one I was used to.

Composed when Beethoven was completely deaf, I can safely say those string quartets, opuses 127 to 135, are the deepest music I know. And then there’s Mozart prancing around like a ninny in Amadeus. But not really. He was, in fact, one of the greatest child prodigies in history who produced an avalanche of sensational music before dying aged 35. No 22 year old has produced a work of such clear-eyed genius as his Sinfonia Concertante for violin and orchestra. Any of his piano concertos numbered in the 20s is proof that the sugar coating popular opinion has often put on him does a complete disservice to the depth, profundity and sheer brilliance of his work.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here. These discoveries were still one or two years down the track. My first real connection with classical music came with the piano music I listened to at the very start of my journey, and more specifically Chopin’s Nocturnes as played by the legendary Polish-American pianist Artur Rubinstein.

A series of perfectly titled moonlight vignettes, these miniatures had tinkled away pleasantly enough in the background until about listen eight or nine where they suddenly went from being an attractive distraction in the next room to becoming some of the most beautiful music I’d heard.

All I’d had to do was listen. Enigmatic, mysterious, these are works of deep pianistic poetry that go way beyond being ‘pretty’ or decorative. They were the tunes that tuned my ear and turned me on to a whole new world of sound.

I’ve listened to barely any other genre of music since. I’ve jogged for months to Brahms until the grey Bavarian fog that so often shrouded his music lifted and the lovely autumnal haze at its centre shone through. I’ve found a whole second tier of composers and compositions who have moved me just as much as the masters. The proto-ambience of English/German composer Frederick Delius, the warm and deeply humanistic symphonies of the Soviet Nikolai Myaskovsky, the stunning piano pyrotechnics of Charles-Valentin Alkan, a Frenchman who burns and blazes with all the intensity and virtuosity of a Coltrane or Hendrix.

I love how the angular late music of the piano virtuoso Franz Liszt reminds me so much of Thelonious Monk and how a man living in mid 19th century Europe arrived at the same musical conclusion as another in Harlem one hundred years later.

The list goes on — the 104 symphonies of the father of the symphony, Haydn, all triumphs of classicism and form; the incredible song cycles of the tragic Schubert that are just my gloomy cup of tea; the dazzling neo-psychedelia of Claude Debussy.

The laws of nature say there is only a finite amount of songs and sounds in the world but really it’s a bottomless well. I love the fact that I’ll never hear all the music I need to hear and that a sense of discovery and enlightenment lies ahead for the rest of my days.

I find it incredibly affirming that this music, these composers and their stories still reach out to touch me the way they do. Their tales are the eternal ones and they’ll be just as telling in the decades and centuries to come. Shift your ear in the right direction and you’ll find the story they’ve been telling has always been your story, as well as my one, too.

This feature first ran in 1972 magazine by Barkers – produced in collaboration with The Spinoff’s Custom division.

The Spinoff’s music content is brought to you by our friends at Spark. Listen to all the music you love on Spotify Premium, it’s free on all Spark’s Pay Monthly Mobile plans. Sign up and start listening today