There are benefits to being the working parent, like being able to focus on your career and avoiding much of the messy, back-breaking work of childcare. But as Brannavan Gnanalingam explains, they hardly make up for the overwhelming sense of guilt.

I’m very excited about properly meeting Brannavan Gnanalingam on Saturday. I’m lucky enough to be doing a session with him at the LitCrawl (you should come, it’s gonna be awesome! It’s on Saturday!) We have been emailing back and forth about our session and he struck me straight away as being warm and open. I asked him if he wanted to write something for us and when he sent me this piece I almost cried. I felt (I feel) so much of this – on both sides – I felt it when I returned to work and when I was a stay at home parent. And now still, as a stay-at-home but also working-from-home parent, I feel it. I think it will resonate with many of us. – Emily Writes

I am a working parent. There’s nothing unique about that. I show up at my job in the morning, and hope to be able to leave in time so that I can see my less than one-year-old child, just before they go to sleep at 7. Some days I don’t make it. A ten-minute delay caused by traffic or if I miss the half-hourly bus by one minute, could mean a baby-less night. On those days, I hope that they’re awake before I leave the following morning.

One day I decided to leave work slightly early, even though for my stress levels, I probably should have stayed an extra half hour. As soon as I arrived home, my child crawled for the first time. I wonder how much else I’m missing out on, the sense of a life passing by, despite it being a life that I’m responsible for.

I also have to acknowledge how lucky I am as a parent (touch wood): I am not a solo parent, I’m financially-secure, and I have a great family support network. I also did none of the original heavy-lifting; no equivalent of pissing out an apple (apparently the physiological equivalent to childbirth for men). With all of the heart-breaking and difficult times people have as parents or would-be parents, my story is banal.

But it’s easy to feel guilty as the working parent. I am entitled to continue to focus on a ‘career’, while my extremely capable wife has put hers on hold. My women friends who went back ‘early’ have had to justify the reasons for going back full-time. ‘Early’ is used by people in disapproving tones. No one asked me if I went back early. The obligations society place on new mothers with things like ‘mandatory’ breast-feeding, no alcohol, and dietary restrictions create additional knots. They don’t exist for me: if I went out and got rip-roaringly drunk at a work event and ate half a greasy kebab circa midnight, like I did last Thursday night, then society is probably not going to call me the world’s worst parent.

I’ve had well-meaning people at work say, “it’s quite nice to escape to the office,” but I’ve never really felt that. Because I know what I’m missing out on. I go home, exhausted from work, but I want to ensure that I can do as much as I can with my child. Read bed-time stories, even if my child is more interested in eating the book. I don’t want to be one of those parents who never change a nappy, because that is such a dick move. Nor do I want to be one of those parents who expect their partner at home to do the cooking and the cleaning and the organisation and the everything else, on top of looking after a vulnerable human being. I’ve walked in, following a tough day at work, straight into a meltdown, with no choice but to pick myself up mentally to help.

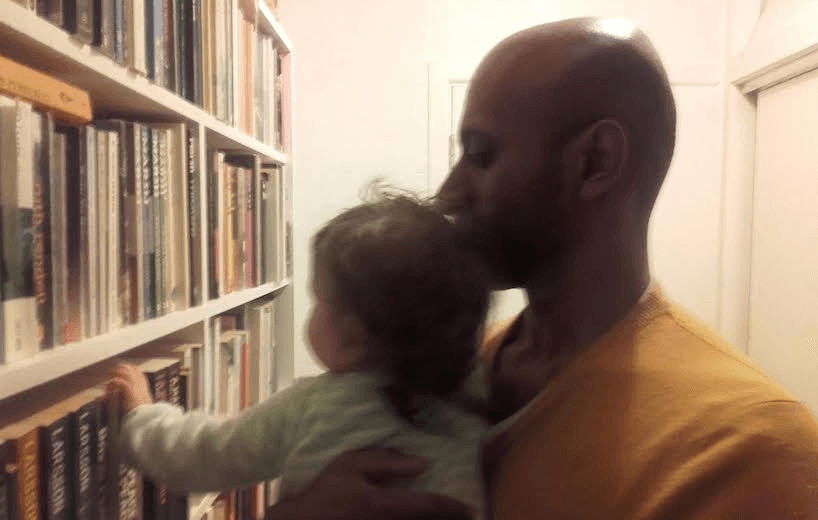

It’s because I don’t want to miss out. I was someone, pre-baby, whose life was governed by FOMO. I’d go to every possible gig and movie I could afford to; if I had three parties on one night, I’d go to them all. Now, with a child, every ten minutes I can get with them is amazing. What adds to the guilt is that, if I can’t be there most of the time, I still can cast myself as the ‘dude’ parent. With such limited time, you want to feel like it’s fun. I can helicopter in and be the one who gets to teach high-fives, have dinosaur noise conversations, or whose bald head incidentally is a useful bongo drum.

I’m also aware that parents who stay at home frequently feel the urge to make it as easy as possible for the working partner when they come home from work. That many will do the early morning feeds, so that the working parent can at least be semi-match fit at work. That many want to limit the work the working parent has to do over the weekend. It must be disheartening in such circumstances – if the working partner is a man – when your child’s first word is “dada”.

We place so much emphasis on work in New Zealand. There’s rigidity to our 9 to 5-ness, and rigidity to this idea that ‘what’ and ‘how’ you do things for financial means is important. Yet these positions barely recognise the reality for most young parents. I’m sure every generation of parents had it tough. But now, what does this mean to young working parents who don’t necessarily have any sense of security? There has been stagnant wage growth since the Global Financial Crisis in New Zealand. What if you’re a young parent in Auckland, whose only way of affording accommodation (whether renting or owning) is to have to commute for hours? What if your child doesn’t sleep or feed well? Will your job cover your day-care costs? What if you have to rely on the precariousness of contractor work, with its potential for limited hours, no parental leave, no sick leave, and diminished employment rights? Or how about student loans, employers’ nervousness in giving jobs to inexperienced people, or internships that pay in “exposure” as opposed to actual money.

This what many of New Zealand’s workers of a child-bearing age face, particularly in this day and age when both parents are likely to be working. It’s not easy. When you hear people who oppose extensions to paid parental leave or further subsidies for childcare or Working for Families, because “you shouldn’t have kids until you can afford it”, I do sometimes wish for sudden and localised lightning strikes. I’m sure there’ll be some folk reading this, who will say, “harden up mate. Back in my day, we used to have our work fax machines in the delivery suite” or “we spent so much time walking in the snow we had no time for our ten children”. But the thing is: it’s hardly a problematic idea to want more time.

Ordinarily, most people have an outlet of some sort, separate from their job. Like vegeing in front of the couch, or ultra-marathon running (both entirely valid forms of stress-relief). My stress relief is the fact I’m a novelist. I’ve published four novels, including one while a parent. My books are, I guess, anarchic and vaguely experimental. That’s not really a sustainable career choice in New Zealand. At best, that’s a golden ticket to cask wine (or in a best-case scenario, soju & karaoke). Being a parent though, crushes that spare time into a tiny cube.

That stress relief is the first thing to go. Guilt. That feeling again.

I’m not a perfectionist, never have been. But there’s something about becoming a parent that makes you want to do the best possible job you can. I can’t stop writing, no matter how much I tell myself to take it easy. I write at 5am and 10pm and weekend nap-times now. I’ll still have to work: in part because I like my job, but also because of that whole money thing. The things that I’m compelled to do, I’ve got no choice but to keep doing them. The reality is that most parents will have to work, if they can. They similarly have no choice, what with contemporary employment and economic pressures. It’s hard not to think about what I’m going to miss out in the future. What ephemeral moments I simply won’t be there for. If time is the best gift you can give your child, it’s a bloody expensive one to find.

Brannavan Gnanalingam was born in Colombo, Sri Lanka in 1983 and is a writer and reviewer based in Wellington. His fourth novel, A Briefcase, Two Pies and a Penthouse was published by Lawrence & Gibson in June this year.