Don’t bet on special treatment for Kiwis in post-Brexit UK. The time remains ripe for a New Zealand republic, writes Lewis Holden

It’s no coincidence that the idea of a New Zealand republic first entered mainstream political debate in 1973. That year the United Kingdom joined what was then known as the European Economic Community (EEC). New Zealand’s Labour Party was in government and was led by Norman Kirk, who was on the record as supporting changing New Zealand’s flag and, if his private secretary is to be believed, not much of a fan of the royals. Kirk’s party debated remits on changing the flag, anthem and declaring a republic at its annual conference. While the remits were defeated – only the anthem was to change later in the 70s, and even then only sort-of – the sentiment driving them, a sense of independence, remained. Even with Brexit now a reality, there’s no turning back the clock, and that sentiment continues.

The economic turmoil in New Zealand caused by Britain’s EEC membership led to the defeat of Labour in 1975 as export receipts plummeted and inflation blew up into double-digits. At the same time Britain voted to remain in the EEC. The feeling of betrayal in New Zealand EEC membership created was summed up in a cartoon of the day which read “I don’t remember Britain being so keen on the Europe in 1939!” It touched all parts of our society. It hurt us not just economically but also shook the way we saw ourselves.

We still feel it today – and along with an electoral miscalculation by an inebriated Prime Minister it set in motion the eventual opening of New Zealand’s economy to the world, and in particular Asia. This, coupled with a resurgence of Māori culture, began the breaking down of the way New Zealand saw itself in the world – no longer a cosy, insular Anglo-Saxon and former British colony. That was, and still is, a deeply unsettling reality to a large number of Kiwis. It is evident in recent debates on our future and in particular the flag debate that that insularity never died.

Fast forward to 2016 and the fallout of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union is only just beginning. In the past 40 years New Zealand has greatly diversified its exports and their destinations, and despite ridiculous protestations otherwise, we’re not nearly as dependent on any one market as we were in 1973.

What the EEC debacle taught us – although sadly not enough of us – is that whatever the geopolitical shifts, New Zealand needs to stand on its own two feet and make decisions that are in our best national interests, and to not make economic policy on nostalgia.

There are those that haven’t learnt this lesson though. During the EU referendum campaign none other than Winston Peters gave a speech in the House of Lords arguing for Brexit and a Commonwealth Free Trade Agreement. This was on the basis that a lot of New Zealanders fought in World War II, and we were betrayed when Britain joined the EEC. The same old attitude recycled for another generation.

No free-trader could be opposed to New Zealand having an agreement within the Commonwealth or directly with the United Kingdom; it is in our best interests to lower trade barriers even if in the case of Britain, we are down to single digits for imports and exports. But having watched most of the televised debates on the EU referendum (I was in the UK during the last three weeks of the campaign) it is clear Peters’ speech was meant for domestic consumption.

What was very apparent was that the priority for a post-Brexit Britain is to join the European Economic Area and stabilise its trading relationship with Europe; the United States was most likely next cab off the rank due to the stalled trans-Atlantic trade deal TTIP. There are murmurings that free movement of migrants from the EU may now not be as restricted as some of the Leave campaigners – especially Winston Peters’ UK equivalent Nigel Farage – have made out. In fact, being a member of the European Economic Area requires it. That means that Commonwealth citizens will still face restrictions on migration to the United Kingdom as the UK government attempts to keep immigration down.

So it is not likely that New Zealanders will be out of the “Others” queue at Heathrow anytime soon. It is unlikely we will see the restoration of the full working holiday visa to anything like what it was during the 1970s, or the restoration of Commonwealth Scholarships. It will still be hard for even well-educated New Zealanders to get highly-skilled migrant visas. The term “British Subject” won’t return to our passports having been removed in 1977.

All of these things matter if not just in a practical way but also symbolically to New Zealanders. Our post 1973 reorienting to the world, while not perfect and far from accepted or complete, is irreversible. Asia still has greater prospects for New Zealand than Europe, and that is unlikely to change anytime soon – especially with Brexit now being a reality. Our advantages in being a former British colony – the English language, common law, parliamentary democracy – mean that we are well positioned to prosper without Britain.

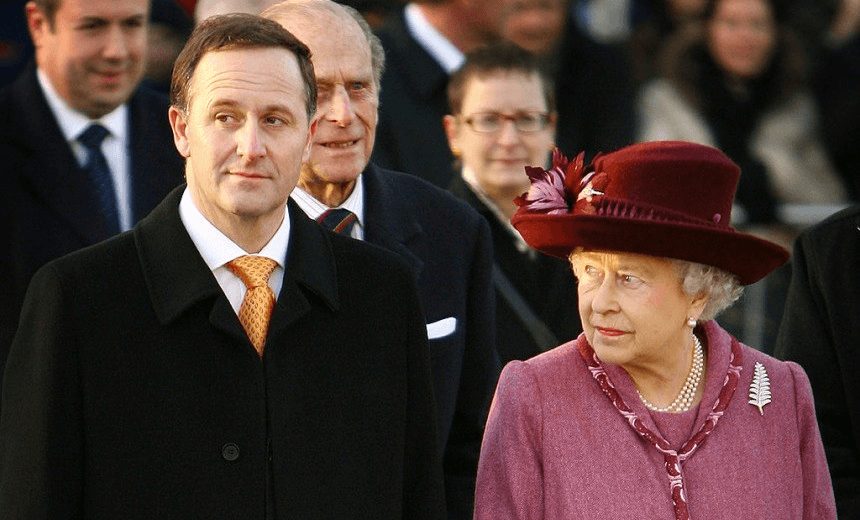

Since the British monarch as our head of State is the last symbolic constitutional link to the United Kingdom, and it is oft-claimed that this arrangement benefits New Zealand, the lack of any headway post Brexit will further diminish the institution in New Zealanders eyes. The claims of tourist dollars following the royals are all well and good (and largely nonsense – they’d come here if we were a republic anyway, since we would still be a member of the Commonwealth) but they are not enough to save the monarchy in the long-term. The changes unleashed in 1973 are irreversible and no amount of living in the past is going to change that.

Lewis Holden is a former National candidate for Rimutaka and former chair of New Zealand Republic, and current chair of Change the NZ Flag.