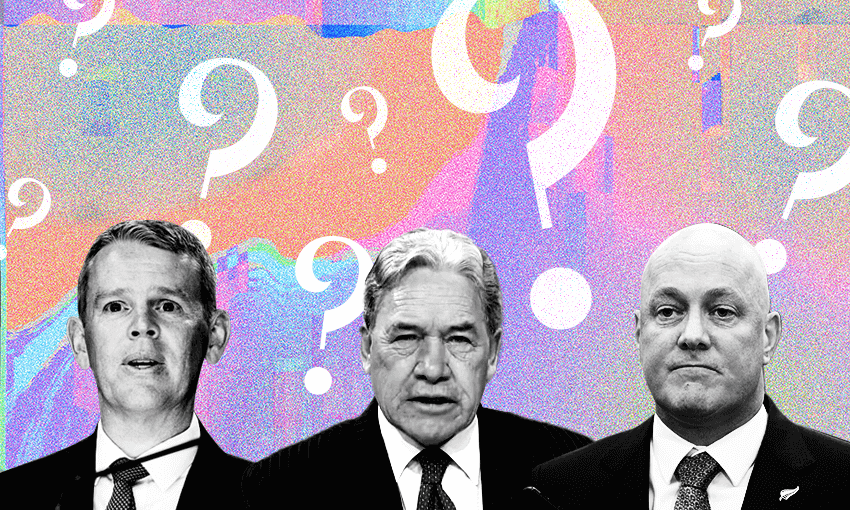

Passions are running high while the potential for meaningful, long-lasting change remains vanishingly small. No wonder voters are feeling bewildered, writes Max Rashbrooke.

“Everything must change, so that everything can stay the same.” This line, from Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s celebrated novel The Leopard, concerns Italian aristocrats confronting nineteenth-century democracy, but could equally be applied to New Zealand politics in 2023. The stakes seem extra high, and the debates extra ugly, yet the space for meaningful political reform is as small as ever. Feeling confused? Then join us as we psychoanalyse the nation in an attempt to explain why this election feels even more bonkers than usual.

Voters are cross, right?

Yes. For many years, the New Zealand electorate was – in global terms – a sunny outlier, like the one picnicker who hasn’t seen the horde of wolves emerging from the wood. Across several governments since the turn of the century, two-thirds of Kiwis said the country was on the right track, even while such confidence measures collapsed overseas. Now, we have joined the pack. Just one-fifth of us think we’re heading in the right direction. Which makes for some very grumpy voters.

Are they wrong to be grumpy? Everything seems rubbish right now.

When it feels like it costs as much to buy a cauliflower as a house deposit cost your parents in the 1970s, it’s no wonder people feel something is wrong with the world. Especially when large parts of that world are on fire.

We did quite well at Covid, though.

Though certainly not flawless, our Covid-19 response was indeed a global success story: we have had fewer people dying than was expected from pre-2020 mortality trends, and employment and economic growth have rebounded more quickly here than in most comparable countries. Inflation, meanwhile, is a global phenomenon. So it does seem an odd time for the national mood to sour.

The electorate, on the other hand, is notoriously fickle. People may keep voting Labour for decades just because of something Helen Clark once did for their family. Conversely, as one minister recently put it to The Spinoff, they sometimes just “bank” political achievements, as if any party would have handled Covid the same way and the government doesn’t deserve particular credit. See also: the dismal Covid aftermath of rising crime and falling school attendance.

OK, so voters are very cross. Presumably they also want very large change.

You’d think so. But there’s no discernible or consistent groundswell. (Except among farmers. Hah!) Some people obviously do want a shake-up: based on the average of the last seven polls, the two main parties’ vote share is just 64%. Over a quarter of the electorate are voting for Act, Te Pāti Māori or the Greens, all of whom offer visions of substantial change.

As far as the collective mood goes, though, these voting blocs cancel each other out. And Labour and National, far from being lured left or right by their minor allies’ success, are tightly hugging the centre line. Sure, there are sizeable differences between the two – on co-governance and renters’ rights, for instance – but when it comes to big-picture questions about the tax take, the role of government or the delivery of services like health and education, their pitches are pretty similar. Labour now spends $27.8bn more each year than it did in 2017, adjusted for inflation; National wants to pare that back by just $2bn.

Are the main parties missing something about the country’s mood?

Probably not. National, in particular, has a huge war chest (thanks, Rich List donors!), much of which it is spending on focus groups and polls. The big parties know pretty well exactly where median voters are, and that group has not – it seems – shifted decisively on the political spectrum.

So the public wants change … but not necessarily from the left or right. No wonder I find this election confusing.

One possible explanation is that many people are so-called valence voters: the questions that determine their political choices aren’t policy-based (whether, for instance, the private sector play a bigger role in delivering public services) but competence-based (whether, for instance, a politician delivers on their promises, whatever those promises may be). Such voters emphasise qualities like honesty, consistency and accountability over more classically ‘ideological’ values such as liberty or solidarity.

While local research on the subject is scarce, there is strong evidence that many Britons, for instance, are now valence voters. And given the received wisdom about this government’s failure to deliver, and the fact that post-Covid everything feels a bit broken, it would hardly be surprising if New Zealanders simply wanted someone who could – to paraphrase Wayne Brown – get things fixed. Hence the political obsession with either burnishing personal credentials or undermining them: recall Christopher Luxon’s endless references to his CEO background, or the CTU’s attacks on him as being “out of touch”.

There is a circularity to all this: the narrower politics gets ideologically, the more people are left with little other than valence votes. Of course, for those who still see politics as a titanic struggle to realise ideals like freedom and equality, the valence voter, relatively unmoved by such battles, is an unfamiliar beast. Nonetheless it exists. (A quick way to tell if you fit into this category: are you reading this on the policy-heavy, politically committed Spinoff? Then you’re not a valence voter.)

OK, fine. It’s a competence-based election.

Absolutely – at least, that is, until you consider that the person most likely to be holding the balance of power, Winston Peters, is not exactly synonymous with competent government, nor indeed the keeping of promises. His king-making ability is also somewhat baffling to the 94% of people who are not New Zealand First voters.

So we’re back at nothing making sense right now. Maybe it will in future, though.

Maybe. Except that if – as seems likely – National does win, Luxon will probably benefit from an upturn in sentiment based on things he did nothing to deserve. The construction pipeline for state houses is already in the thousands, carbon emissions will likely continue their slight falls of recent years, and the economy is – barring a major world meltdown – set to recover in coming months. All of which are achievements Luxon would happily claim. Fair? Not really. But that’s politics. Don’t you love it?