Does Andrew Little stand a chance of leading a centre-left government into Christmas 2017? Ahead of Labour’s caucus retreat this weekend, Simon Wilson considers their task in taking on a new prime minister who is a much more formidable figure than many seem to think

Bill English went to the Joseph Parker fight on December 10. On the way out, a TV reporter caught him for a quick chat. It was the first telling moment of his 2017 general election campaign.

The reporter asked him, did he think Parker should have won? English, looking good in a tux, leaned into the camera and grinned. He said that quite often in a contest you think the aggressor is winning because they’re the one making all the moves. You don’t notice how well the defender is deflecting the blows and tiring the other guy out. The defender might be controlling the match.

He grinned again, practically winked, those boyish good looks filling the screen.

What he did there. In a sea of clichés and babble he gave us a real idea to think about. He showed expertise and used it to deliver a metaphor: few would have thought he was talking just about the boxing. He mashed up intellectual smarts with the basest sporting contest ever invented, and he did it modestly, with an appealing off-the-cuff informality. In just a few seconds he was memorably entertaining.

Joseph Parker became WBO heavyweight champion of the world that night. Two days later Bill English became prime minister. That Saturday, he revealed he will be a formidable contestant in the election later this year.

English likes to say John Key gave him a daily masterclass in leadership. Such modesty. In the same situation Key would have spoken in platitudes and been entirely forgettable. He wouldn’t even have grinned: Key doesn’t really have a grin. It will not be long before Key’s old supporters start saying, what on earth did we ever see in him?

Hope everyone’s had a relaxing day with their families opening presents. Here’s something that Santa dropped off for me. pic.twitter.com/bTOohdcucw

— Bill English (@pmbillenglish) December 25, 2016

None of which makes Bill English unbeatable. He could fuck it up all by himself. He lacks Key’s great attribute as a leader – a calmness under pressure, which derived from his lack of concern for what happened. On most issues Key didn’t have a preferred outcome, apart from remaining popular. (He even said as much in an exit interview: more than most people, he volunteered, I like to be liked. It was a frank admission he was motivated less by doing the right thing than by vanity.)

But English cares what happens. He’s got values and he’s got an agenda. Key is a likeable guy who had to learn to look like he gave a toss, but English is a conviction politician who’s had to learn to moderate his feelings.

He can also be awkwardly unfunny. On the last sitting day of Parliament last year he made a lame attempt to abuse opposition leaders Andrew Little and James Shaw using Taylor Swift lyrics, stumbling over the words and not seeming to know their original context. If you’re going to play in the pop world, you need a way surer touch.

Bet he finds it, though. One thing English really can learn from Key is how not to repeat mistakes: you get it right or never do it again. Key didn’t mince down another catwalk, pull any more ponytails (after he was outed) or bend to pick up a second bar of the soap.

English’s greatest problem is that underneath it all he’s still Boring Bill. The day he announced his candidacy for party leader he mumbled into the microphones, droned on and on saying nothing of consequence, forgot to project any kind of personal appeal. He possibly thought he would be sleepwalking to victory.

Within hours, though, on the evening shows, English was presenting an entirely different side: bright and lively, the people’s friend. His great advantage is that after years playing Serious Money Guy no one will ever doubt his gravitas, so he can go all impish and it won’t undermine him.

Party leader Bill English failed catastrophically at the ballot box in 2002, but since then Finance Minister Bill English has become enormously respected. This time round he’s got the chops. And, it turns out, Boring Bill is also very good at being the Entertaining Mr English.

You can’t say the same for Andrew Little.

One morning a few weeks earlier Little was on RNZ’s Morning Report talking to Susie Ferguson. She asked him, what was Labour going to do on day one to improve the lives of New Zealanders? It didn’t sound like a hard question, but Little couldn’t answer it. He talked about jobs and health and education. She seemed surprised and pressed him. He seemed affronted and repeated his answer. It went on like that.

Half an hour later I sat down with Little for breakfast and asked him about it. In the age of Trump, how does any politician not grasp the importance of a Day One declaration? He disagreed. He talked about how there’s not really any such thing as Day One, because you need enquiries and new laws and so on. He didn’t get it. Day One is far more than a promise to fix a problem quickly and decisively, although that’s valuable in itself. It’s a statement about who you are. It’s the way to tell voters: We stand with you. We are not going to be undone by detail and compromise. We are energised and determined and we are going to make a very big difference.

If you’re Donald Trump, it’s easy. Day One, we build a wall. But on the centre-left you’re not promising bullshit so it’s more complicated. Yet the message can be just as compelling. Why doesn’t Andrew Little say: Day One, we start set up a taskforce for healthy children?

We won’t finish the job straight away but we will get started straight away. No task is more urgent and we will clear the decks to get it done. All children have the right to live in a warm, dry home. To not go to school hungry and to be protected from the poison of food that will kill them. To be safe from abuse at home and to be free of the crippling diseases of poverty. To have the opportunity to prosper.

Nobody denies those are legitimate goals in a civil society. Andrew Little espouses them often. What he doesn’t do is promise Day One. He doesn’t signal that the commitment is deeper and more urgent than the easily spoken words.

There are lots of ways to declare a Day One campaign. You can do it with very specific promises: Little could promise an immediate rise in the minimum wage. And in benefits. Immediate funding for more police, more housing construction; an immediate tax concession to employers who incentivise staff to leave the car at home.

There are so many options. Labour just has to choose some. The deeper issue is: Labour needs to be urgent and on the march. And yet, as it headed into Christmas, with National changing leaders and suddenly looking vulnerable, Labour missed all its chances to do that.

A few weeks later Andrew Little appeared on Kathryn Ryan’s Nine to Noon show on RNZ and it was the same story all over again. She fed him “aren’t you going to do this?” lines and he obfuscated. He got angry. Angry isn’t urgent. Angry is alienating. Urgent is inspiring.

Meanwhile, Bill English announced his new cabinet and was promptly criticised for being more cautious than daring. So he’s not a daring politician, we knew that. But he is a purposeful reformer of government spending and much of the criticism misjudged his skill. He created a cabinet to support his programme.

All of the main contenders to replace English – should he collapse in the opinion polls or lose the election – have been given jobs to bring out the best of them rather than the worst.

Take Judith Collins, who got demoted, to remind her who’s boss, and removed from the law-and-order portfolios of Police and Corrections. Her new job as Minister of Revenue invites her to apply her manifest abilities and uncompromising view of criminals, not to the “underclass” but to tax evaders. Do we live in a universe where she might do that? I think we do. Is it what English wants? I assume it is.

Simon Bridges has been invited to continue his slow but steady modernisation of the country’s transport infrastructure, and has been given the complementary role of Regional Development, which strengthens his hand. Murray McCully kept Foreign Affairs in order to see through our UN duties, especially in relation to the Security Council resolution on Israel. All of these were smart, forward-looking appointments.

The anti-reform, backward-looking Steven Joyce got English’s old job, but the relationship of these two old antagonists has shifted decisively: English is now in charge. As for the so-called backbench revolt: pfft. Promotions that were widely expected under Key took place; very little else happened.

And what of the new deputy, Paula Bennett? She’s a high-energy bundle of funtimes, which will help keep English lively. She’s also quick and mean, always keen to rip an opponent to shreds. She could become a powerful campaigner.

But she lacks a decency filter and that makes her a bully: witness those attacks on private citizens victimised by the welfare system. Bennett displays a contempt for suffering common to those who have recently joined the patrician class. She’s Cruella de Vil.

My reading of National’s leadership “contest” in December is that it was a well-organised manoeuvre to ensure Paula Bennett did not become prime minister. It’s significant she has been given an enormous workload: English is keeping her busy.

It’s even more significant that despite her experience with welfare portfolios she is not the minister in charge of “social investment”. This is the flagship philosophy underpinning English’s reform big strategic project to reform the welfare state. The job of coordinating it is by far the most important in English’s cabinet, after his own and Joyce’s, and has gone to the competent rising star, Justice Minister Amy Adams. I’ll come back to this later in the week.

It used to be a commonplace that the day John Key resigned all bets about the future of the National-led government would be off: the party, it was assumed, did not have a successor capable of maintaining its extraordinary popularity.

Don’t count on it. Bill English has a powerful, forward-looking front bench. They are energised by their new leader and comfortable mixing reformism with the innate conservatism of the centre-right. They’ll steal winning ideas from anyone – especially Labour, as they have shown with their appropriation of parts of Labour’s impressive Kiwibuild programme.

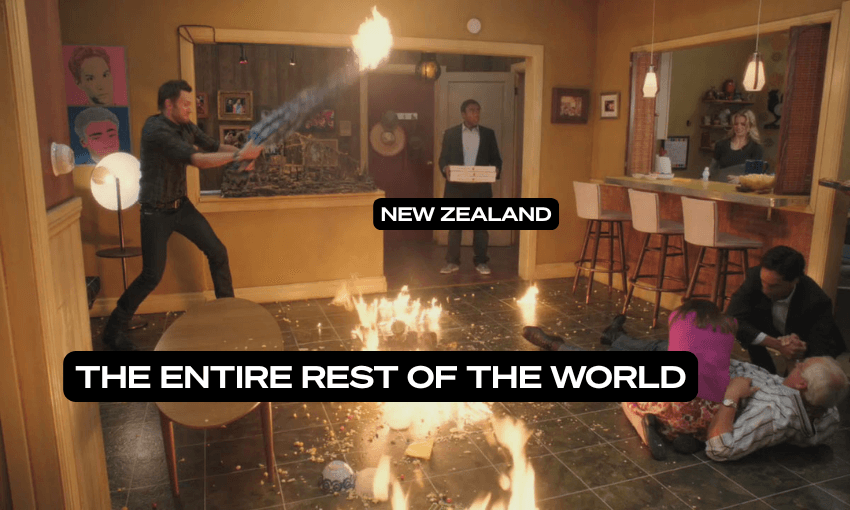

Boring Bill English could lose the election for them; Pandemonium Paula could do that too. But Labour should not rely on it. Bill English is a sophisticated, likeable and confident leader – and that means this election will be as hard for the centre-left to win as ever.

But it can be done. Provided, that is, Labour – and the Greens with them – find their A-game. They need to do that very quickly.

This is the first in a series of pieces on election year and the Labour Party by Simon Wilson. To come: The A-game with Andy Little; the great challenge of “social investment”; identity politics and the failure of the broad church; the lessons from Trump are not what you think; National’s Index of Shame.