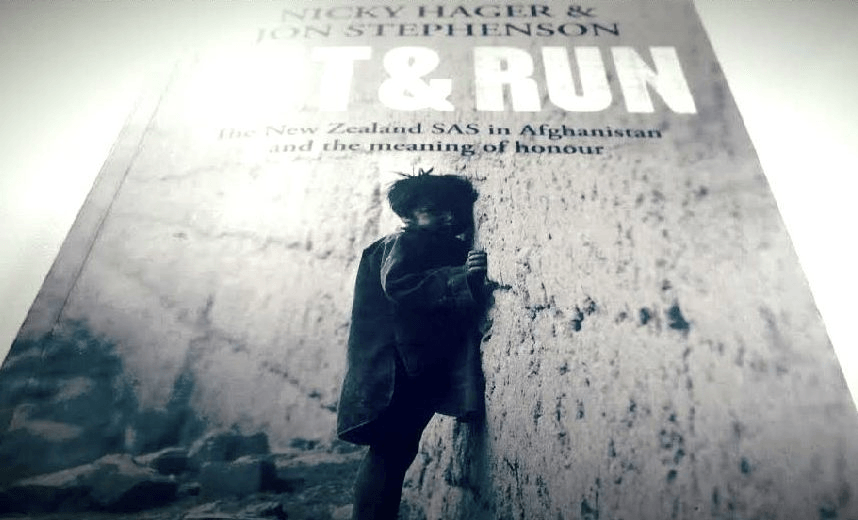

In their new book Nicky Hager and Jon Stephenson offer evidence of a botched raid that killed six civilians and led to a scramble to conceal the truth. Danyl Mclauchlan reviews Hit & Run: The New Zealand SAS in Afghanistan and the Meaning of Honour and weighs up the prospects for an inquiry.

This review was first published in March 2017

Not so long ago nation states went off to war in the name of their king, or country, or for the glory or honour of the people, or the workers or their race, or the nation itself. Nowadays western democracies like to tell ourselves we go to war to champion things like justice and human rights, and to defeat evil foes that fail to uphold these values. But these are shaky justifications for war, because they’re usually the first things we abandon when the inevitable moral compromises, blunders, pointless atrocities and general horrors of warfare unfold.

That’s what Nicky Hager and Jon Stephenson claim happened in 2010, towards the end of New Zealand’s 12-year deployment to Afghanistan. Stephenson has covered Afghanistan since the US invasion in 2001, and Hager’s 2011 book Other People’s Wars was an in-depth study of our role in the conflict. It was based on a large trove of leaked documents and described a culture within the NZ Defence Force that understood the importance of marketing our role in the war to the public as one of peacekeeping, nation-building and upholding human rights, but showed that our involvement was driven by an almost comic obsession among defence officials to “get in on the game” and engage in combat operations alongside US and UK troops.

The deployment won the reluctant support of the Clark government and the enthusiastic support of the Key government, because the US rewards allies with visits to the White House and reciprocal visits by senior US figures, and these visits are regarded as extremely prestigious by political and media elites. “Getting in on the game” has its perks.

Hit & Run is a study of what “the game” really looks like. It describes a botched raid on an Afghan village, which resulted in a number of civilian deaths, the raid’s aftermath and subsequent cover-up. Stephenson travelled to the remote valley where the raid took place and interviewed the villagers; Hager interviewed sources within the New Zealand military and compiled the material. Like all of Hager’s books this one is a mixture of detailed reporting, analysis and editorialising. It is a powerful combination for readers already inclined to agree with his view of the world; it is also a convenient pretext for the subjects of Hager’s books to dismiss the author as an activist and conspiracy theorist.

The allegations in some of Hager’s earlier books – that National Party leader Don Brash was secretly collaborating with the Exclusive Brethren, or that the prime minister’s staff were conducting smear campaigns via a deranged “attack blogger”, or that New Zealand had joined a secret global surveillance network – all seemed so bizarre they demanded further attention, and they all turned out to be true. The allegations in Hit & Run are shocking on a human level, but the notion of vengeful soldiers accidentally killing civilians and their military and political masters covering it up is such a depressingly credible claim that their greatest risk is probably not disbelief but indifference. Defence officials will be hoping that the public will accept that such things happen in war and move on. They might not be wrong.

So what happened? Everyone seems to agree that on the 22nd of August 2010 the SAS conducted a nighttime raid on two remote villages in Afghanistan, supported by US helicopter gunships. The outcome of the raid is disputed. Hager and Stephenson have called for an independent inquiry to find out what really happened, but near as they can tell the story goes like this …

Two weeks before the raid New Zealand soldier Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell was killed in a roadside attack by “insurgents”. The New Zealand intelligence operatives in Afghanistan made contact with their local informants to find who conducted the raid, and where they lived, so they could be captured or killed. Hager and Stephenson make much of the fact that this was a “revenge raid” or reprisal, and I’m sure that’s how the soldiers saw it too, but it was also, given the parameters of their mission, their job. They also insist that the intelligence was faulty: but the informants seem to have correctly identified the insurgents, and their houses.

What they didn’t determine was that the insurgents had anticipated a revenge attack, such things being a routine part of Afghan life since the Soviet invasion in the 1980s, and fled their homes to hide out in the mountains. So when the SAS and their US air support conducted a midnight raid they were attacking a village that mostly consisted of children, women and elderly farmers. Hager and Stephenson allege that SAS snipers may have shot some of the villagers as they fled during the chaos of the attack, and that the helicopter gunships destroyed several of the houses in the village, killing four more civilians and seriously wounding fifteen.

The next day the raid was reported as a success by the International Security Assistance Force, which oversaw coalition operations in Afghanistan. It claimed that 12 insurgents and no civilians were killed. There was no mention of New Zealand’s involvement in the operation. After coverage of the raid in the international media, ISAF conducted an investigation and, a week after the raid, determined that “several rounds from coalition helicopters may have fallen short” due to “a gun sight malfunction” which “may have resulted in civilian casualties”.

A week after that Hager and Stephenson allege the SAS returned to the village and blew up the houses they’d destroyed, which the villagers were attempting to rebuild. It’s very hard to believe that the destruction and deaths were caused by a “weapons malfunction”, or the rash actions of US pilots if the SAS snipers were killing fleeing villagers, and then flew back to the village two weeks later and deliberately blew up the very same buildings again.

As details of the raid have slowly bobbed to the surface over the years – in Stephenson’s reporting, Hager’s previous book on the conflict, a story by reporter Guyon Espiner – the ministry’s line has changed from insisting that there were no civilian casualties, to insisting that New Zealand troops weren’t responsible for any civilian casualties. And there’s no need for another inquiry because there’s already been one, and everyone got exonerated. Problem solved.

If any war crime did take place, it is hard to imagine the politicians and military officers who have been covering it up for many years, and carefully massaging and reparsing their public statements to evade any accountability, are going to agree to the kind of wide-ranging inquiry Hager and Stephenson are calling for. Maybe they’ll surprise us.

The last chapter of the book raises a deeper issue. It’s obviously based on interviews with disenchanted defence staff, who think that the ultimate cause of the raid is a change in the culture of their department. The high command of the New Zealand military, they argue, is increasingly dominated by former SAS officers: a tiny but highly influential component of the overall organisation. They worry that the culture of the SAS is one of secrecy, elitism and unaccountability, and it is transforming our military into an organisation that privileges the operations carried out by special forces, like raids and targeted assassinations. It also acts as its own lobby group, petitioning Australian and US officials to request SAS involvement in their military adventures.

Critics of Hager and Stephenson might dismiss all of this. “We need the SAS,” they might say. “Because the world is a dangerous place. And, yes, something terrible might have happened here. But terrible things happen in war. The greater terror is to stand by and wring our hands and do nothing, and let the Taliban win. Tragic accidents in war are the price we pay for peace.”

Unfortunately for this argument – and, no doubt, even more unfortunately for the people who live in the area where the raids took place – the entire region is now in effect controlled by the Taliban. New Zealand withdrew our forces in 2013, shortly after three more New Zealanders were killed. “To cut and run now would not honour those deaths,” John Key insisted, but also announced that the troops would withdraw “as fast as we can”.

The lives lost – both Afghan and New Zealand – the blood spilled, and the billions spent all seem to have been for nothing. In a military sense, at least. If you look at the big picture, the prime minister got to play golf with the president of the US, and the officers and public service mandarins who lobbied for the war seem to have been generously rewarded with medals and promotions and honours, for all their important work defending justice and human rights.