A former member of the Reagan administration recalls the clash with NZ over a nuclear ship visit – and offers a fresh warning about Trump.

Uranium on your Breath, the third episode of Juggernaut: The Story of the Fourth Labour Government, is now available wherever you get your podcasts.

David Lange called it “the highest point of my career in politics”. In defiance of diplomatic advisers urging him to decline the invitation, the New Zealand prime minister travelled to the Oxford Union in March 1985 to debate televangelist Jerry Falwell on the morality of nuclear weapons.

Lange began his speech – broadcast live in New Zealand on a Saturday morning – by suggesting that President Ronald Reagan would be paying close attention to the event from the White House.

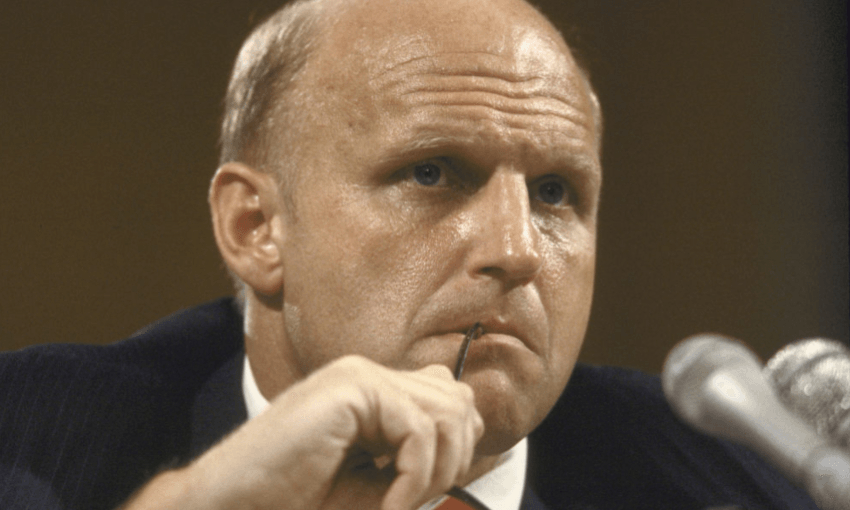

Washington DC was indeed tuned in, according to Richard Armitage, a former senior US diplomat who was engaged in relations with New Zealand as assistant secretary of state. Lange’s efforts went down, he told the Spinoff for the podcast series Juggernaut, “like a turd in a punchbowl”. The sentiment expressed was “neglectful of what an alliance meant”.

The line from the debate that endures more than any, nearly 40 years on, is Lange’s response to an audience question, in which he exhorts his interrogator to hold his breath – “I can smell the uranium on it”.

“The one thing the Americans never forgave me for was that interjection and that was deemed by them to have been a terrible slight on the relationship,” Lange would later tell the documentary series Revolution. “And it says something for my inability to understand what American sensitivities are about.”

Richard Armitage, a Pacific specialist in the Reagan administration, had first encountered Lange in 1982. The then leader of the opposition “listened carefully” to his outline of the US position: the Anzus alliance of New Zealand, Australia and the US would be meaningless if the partners couldn’t conduct military exercises in one another’s waters, and the US, in the depths of the cold war, simply would not confirm or deny the presence of nukes on any ship.

Despite Labour’s anti-nuclear stance, “he understood the need for our policy,” said Armitage. While there was no explicit undertaking from Lange that he would make an American ship visit happen, “he certainly led us to that belief”, Armitage said. The impression was that “he was willing to face down the left of his party on this issue”. Armitage would subsequently conclude that Lange had been “disingenuous”.

George Shultz, the US secretary of state, emerged from an informal meeting with Lange following an Anzus summit in Wellington just two days after the 1984 election believing he had received an unambiguous undertaking on the matter from the prime-minister-elect, that he’d turn the policy around within six months. Lange would later reject that version of events, calling the ongoing speculation “tiresome”.

Twenty years after that meeting, Lange found vindication. At a 2004 conference to mark the 20th anniversary of the election, Merv Norrish, who had been the only New Zealand official in the room as secretary of foreign affairs, spoke for the first time about the meeting. He suspected Shultz had “convinced himself” that Lange had issued a pledge. “I did not interpret Mr Lange’s comments that way,” said Norrish. “It seems to me Mr Shultz heard what he wanted to hear and that subsequently coloured his attitude to Mr Lange.”

The New Zealand decision to refuse a request for the visit of USS Buchanan – an issue that surged into the public domain while Lange was largely incommunicado in Tokelau, following leaks in Australia and the US – was mystifying, said Armitage. If Lange had “bothered to consult with any military person in New Zealand, they would have told him the USS Buchanan was an older ship, hence very unlikely to be nuclear capable”.

In fact, advisors had said essentially that. Officials concluded it was “most unlikely” to be nuclear armed. But that wasn’t good enough to satisfy the deputy prime minister, Geoffrey Palmer. “The advice that we got was inherently ambiguous, because it confirmed the neither confirm nor deny policy,” he told the Spinoff. To have signed off a visit would have caused “uproar”.

The decision, which led ultimately to New Zealand being sidelined from Anzus, prompted “sadness, disappointment, total disbelief”, said Armitage. New Zealand had understood there would be consequences. An editorial in the Economist at the time helpfully reminded Wellington: “Nice people are hard to wag legal fingers at, but nice New Zealand has to be reminded of the law that there is no quid without a quo.” Shultz and Reagan had both stressed from the start, however, that there would not be trade reprisals.

Today, Armitage says he remains fond of New Zealand. Asked for a view on the Aukus treaty, he was “very positive about any greater efforts New Zealand makes in the defence area”. Involvement could not easily extend to the submarine project at the core of the agreement. “It’s not easy to be involved with a nuclear submarine. There’s a bandwidth in terms of academic training required to be a nuclear sailor.” The pillar two possibilities – “other involvements or other activities” – made sense, however, he said.

A lifelong Republican, Armitage has been a vocal critic of the domination of the party in recent years by Donald Trump. What would his potential re-election later this year mean?

“In my view, Mr Trump hasn’t gotten any smarter from 2016 to now. So he won’t know any more about how to run a government should he win. But the people around him, they now do know. So they can be more mischievous,” he said. “There’s no question that he’s much more isolationist. He doesn’t care in my view, at all about New Zealand … I think Mr Trump’s attention to Asia would come after several other things. Nato comes first, I think.”