Talk of a resurgent Mana Party, unshackled from Dotcom and buoyed by a Māori Party pact, has prompted suggestions of a new order in Māori politics. Morgan Godfery explains why he’s just not buying it

Ika Table Talk: From 7.30pm on Wednesday November 29, Ika Seafood Bar and Grill and the Spinoff present a discussion on Māori parliamentary politics, hosted by Mihingarangi Forbes of RNZ, with author and commentator Morgan Godfery, Labour candidate Tamati Coffey, Hui producer and Spinoff podcaster Annabelle Lee and Māori Party secretary Amokura Panoho. The event will be livestreamed by the Spinoff via Facebook. More details here.

Someone needs to invent a Hone Harawira insult archive: John Howard is a “racist bastard,” Phil Goff is just a “bastard,” the tobacco lobby is made up of a bunch of “pricks,” and most of you – dear readers – are probably “white motherfuckers”. Oh, and Māori MPs in National are John Key’s “little house n******.”

This is the puzzling thing about Hone Harawira – he said all of this and more, yet he would go on to win election after election. In 2012, only a year after an ugly breakup with his former colleagues in the Māori Party, Harawira topped a poll asking respondents to name the MP working hardest for Māori rights.

I suppose there’s one piece to the puzzle. Most Pākehā might hate his guts – he’s a reverse racist, or something like that – but Māori understood his heart. It’s a little-known fact that Māori MPs are the hardest working parliamentarians. They cover the largest electorates and they clock the longest hours.

Take Te Tai Tonga, the old Southern Māori seat, running from Petone in the North to Stewart Island in the south and then tracking east to the Chatham Islands. In physical terms, Labour’s Rino Tirikatene is responsible for representing more than half of the country.

In population terms, Te Tai Tonga is more or less the same size as any other electorate. But the social expectations of a Māori MP are different to what other New Zealanders might expect of their constituency MP. When the Kaikōura earthquake struck Rino Tirikatene took the first trip down to help out in the kitchens at Takahanga Marae.

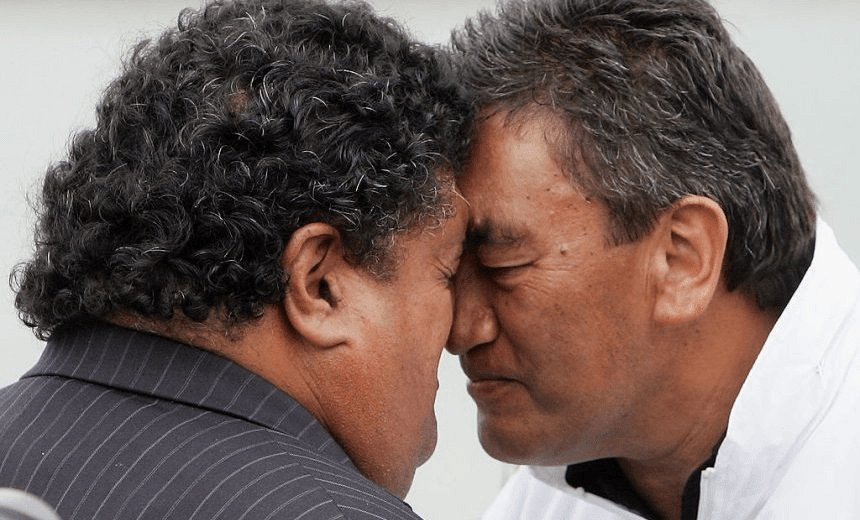

The term for this is kanohi kitea – a tricky one with a double meaning. In the past the term meant raid or incursion of some kind, but today we use it to describe someone who’s seen. It’s not enough for Māori electorate MPs to deliver magnificent speeches on the latest bill before the House. It isn’t even enough to make the Cabinet. Instead you must show up at every birthday, tangi, community fair and prizegiving that you can.

When I interned for the late Parekura Horomia, the former Minister of Māori Affairs and the long-serving MP for Ikaroa-Rāwhiti, we called it (behind his back) “the Parekura Method”. It wasn’t uncommon for Parekura to arrive on your doorstep unannounced, and for no other reason than he was in town and wanted to catch up. It usually takes seven hours to drive from Wellington to Mangatuna, but it usually took Parekura more than two days.

This is why Shane Jones once said, “Parekura … will prove to be the most popular parliamentarian to the Māori people”. And this is who Hone Harawira took lessons from. Parekura used to joke that the only person he ever sacked was Harawira. “Don’t be like him,” he’d warn me. Although Harawira would give Parekura a hard time in their parliamentary years – even accusing him in 2008 of using “bribe money” – just like every other Māori electorate MP Harawira was a student of the Parekura Method.

This is why it’s hard to write off the Mana Movement, 2.0. Harawira is making peace with his old enemies over bacon and eggs. Labour’s Kelvin Davis, the current MP for Te Tai Tokerau – Harawira’s old patch – is an outstanding MP and perhaps the most reliable performer in his party, but the political and social conditions in 2017 will hardly resemble the conditions in 2014.

What did Harawira in at the 2014 election was not so much his mouth (or even his record), but the decision to align with Kim Dotcom and the Internet Party. On election night the contrite Internet Party founder was moved to take “full responsibility for this loss tonight because the brand – the brand Kim Dotcom – was poison for what we were trying to achieve”.

Davis knew it well before the results rolled in on September 20, writing on Facebook in August, “I’m just an ordinary Māori living up north trying to stop the biggest con in New Zealand’s political history from being pulled against my whānau, my hapū, my iwi.” Davis was skilfully framing this as an election between himself and Dotcom, not a contest with Harawira. After securing the seat Davis admitted to media that Dotcom was Harawira’s “Achilles heel” and memorably condemned Internet Mana as “all steam and no hangi”.

This year, Dotcom is helping elect Donald Trump, meaning Harawira can run against his record at the next election. There’s reason to believe this could work. In 2005, 2008, the 2011 byelection and the 2011 election the people of Te Tai Tokerau comfortably endorsed Harawira’s record and returned him to parliament. Were this to happen again – but with the help of the Māori Party who’d presumably stand aside in the electorate – some political commentators are speculating that it could mean a “reordering” or “realignment” in Māori politics.

Don’t believe the hype.

The thinking goes a little something like this: if the two kaupapa Māori parties cooperate, one win is certain (Māori Party co-leader Te Ururoa Flavell in Waiariki); one is probable (Harawira in Te Tai Tokerau); and two are possible (the Māori Party’s Howie Tamati in Te Tai Hauāuru and perhaps Māori Party co-leader Marama Fox in Ikaroa-Rāwhiti). If the right candidate steps forward in Hauraki-Waikato that electorate is “in play”.

Let’s imagine for a moment the Māori Party and Mana Movement secure five electorates. This could create a two-seat overhang, possibly denying New Zealand First the power to choose the next government. If the two parties win the seven electorates – very unlikely – this could create a four-seat overhang, almost certainly denying New Zealand First the power to choose the next government.

“Deputy Prime Ministers Te Ururoa Flavell and Marama Fox.” How does that sound?

Were this to happen the Māori Party could finally fulfil its founding promise as the “permanent Treaty partner”. The party with the power to make or break governments. Yet the very possibility Te Ururoa Flavell and Marama Fox could decide the next government gives Labour’s its best line: “a vote for the Māori Party is a vote for National.” Remember that Māori electorate voters remain stubbornly Labour, with the party winning six electorate seats and nearly half of the party vote at the last election.

Granted, this is down from its 82 per cent share of the party vote in 1972 or its 78 per cent share in 1984, but it really would take a dramatic realignment or reordering for Labour to lose even three electorate seats (let alone all six). Isn’t it amazing how Māori vote in such overwhelming numbers for Labour? Most Pākehā tend to misinterpret what this means, shifting awkwardly as they imagine Māori communities as cradles for left radicalism. But in truth decades-long loyalty to Labour is a better sign of conservatism than radicalism, at least conservatism of the temperamental kind.

What most Pākehā don’t understand because they don’t know history and what the Māori Party refuse to acknowledge because it’s inconvenient is Labour has always occupied “the centre” in Māori politics, usually with the conservative and rurally dominated Māori Council to the right and the progressive Māori Women’s Welfare League and trade unions to the left. Sometimes Māori in Labour shift left, as they did under the old trade unionist and legendary radical Matiu Rata, other times they return to the centre as under Koro Wētere and Dover Samuels, and today they occupy the soft left (thanks in part to former Māori Women’s Welfare League life member Parekura Horomia).

Labour understands its place yet the Māori Party is stuck in a tight knot, slumped over the Cabinet table in a cold sweat as its co-leaders figure out how to reconcile the tension of their insider-outsider status. If a “realignment” or “reordering” is happening it will only happen after Flavell and Fox have squared their status as a party of government with their positions outside of Cabinet. It’ll happen when they reconcile their status as leaders of a parliamentary party with the social movement they came from. It’ll happen when they can, as Sir Āpirana Ngata once put it, “reinterpret the Māori point of view to Pākehā power.”

Sir Peter Buck was a professor of anthropology at Yale University, a medical doctor in the Middle East, a museum director in Hawai’i, and an accidental Māori MP after Hone Heke – the member for Northern Māori – died suddenly in 1909. After escorting Heke’s body back to his ancestral marae in Kaikohe, Buck’s mentor and the deputy Prime Minister Sir James Carroll took to his feet at the tangi and announced how Heke’s mother wished to “marry their son’s widow to a chief from the South”, a tribute to Buck for taking the punishing journey from Wellington and returning her son home.

There are excited whispers and Carroll senses his chance. He remains on his feet, wielding his tremendous mana on Buck’s behalf, and gently reminds the local tribes that Buck is now in credit and a debt is owed. Utu, or reciprocity, is due. Should they wish to restore balance perhaps they would consider Buck as their new MP (Carroll did this without consulting him, of course). Buck went on to win handily, even though he faced several local challengers and traced his whakapapa further south.

It’s the kind of thing that could only happen in Māori politics and it’s one reason political commentators often assume Māori politics adheres to a kind of tribal logic. In 1868 the Under-Secretary for the Native Department William Rolleston was so fearful of “tribal jealousies” shaping the first elections in the Māori electorates that, instead of calling for nominations and establishing polling places, Rolleston called an “assembly” to settle on one candidate and in the event of two nominations to settle it on a show of hands.

Assuming the same tribal considerations shape Māori politics today is naïve, perhaps even racist because it means assuming Māori society exists in a pre-modern past, yet whakapapa (descent) remains the organising principle in Māori politics. Keen to stand in the Waiariki electorate? Think again unless you can whakapapa to either the Te Arawa or Mātaatua waka. Keen to stand in Hauraki-Waikato? Better find a connection to the Kingitanga, then. Keen to stand in … Well, you get the picture.

The contradiction is Labour understands this and reinforces it. In the post-war era Te Tai Tonga has been out of the hands of Labour and the Tirikatene whanau for only 15 of the last 70 years. Rino is the third generation Tirikatene to hold the seat. Labour’s Tāmaki Makaurau MP Peeni Henare is the great-grandson of Northern Māori MP Taurekareka Henare while Te Tai Hauāuru MP Adrian Rurawhe is the grandson of former Western Māori MPs Matiu Rātana and Iriaka Rātana.

You might accuse Labour, the workers’ party, of pandering to tribal aristocracies.

Of course, there’s some of that. But there’s also memory. The first Labour government is responsible for building the welfare state, resolving the Ngai Tahu and Waikato compensation claims – Prime Minister Fraser personally settled the Whakatōhea claim – reforming the Māori electorates and even replacing the use of “Native” with “Māori” in all official documents. The New Zealand Herald would publish regular cartoons showing Fraser pandering to Māori in grass skirts (pandering to “the Māori mandate”, as the cartoonist put it).

This is why it is unfair to assume Māori allegiance to Labour is slavish or that Labour unreasonably exploits that allegiance.

As Henare Tuwhangai said in 1985, to be Māori is to share the world with one’s ancestors (both recent and ancient). This isn’t some mystical solipsism but a plea to cherish relationships. Sometimes you’ll see this on the marae when the old folk recite histories as if they were there. If you read 19th century Māori Land Court records you’ll find elders reciting history as if they were participants in it. In other words, when Rino Tirikatene stands in Te Tai Tonga he isn’t just standing on Labour policy, he’s standing on his relationship between his ancestors and yours.

It’s more than a little odd that Labour understands how history, whakapapa and memory shape Māori politics, yet on almost every other detail to do with New Zealand politics the party is incompetent. I suppose the party’s Māori MPs understand the future is ngā rā o mua, or the days in front, while its other MPs think of the future and a break with the past. For this reason you shouldn’t expect a realignment or re-ordering in Māori politics just yet.