In March, sudden changes to purchasing rules highlighted the ongoing struggles of the disabled community – and advocates say extra money allocated to Whaikaha in the budget can’t come close to countering chronic underfunding.

Cherie Cawdron has driven the same exact loop around her neighbourhood hundreds of times: driving is one of her son’s favourite activities, something he’d like to do all the time. The petrol costs add up quickly. Her son, now 20, has a number of complex, overlapping disabilities and health conditions: an intellectual disability, autism, a physical disability, and a medical condition that requires the use of an oxygen machine at night to help him breathe. Caring for him isn’t a simple task, because his individual needs don’t fit into exact boxes that the government system often wants to check off. As well as the petrol costs, last month, her family’s water bill was $198 and her power bill was $450 – a consequence of as many as four baths a day, which help soothe her son. She and her husband both work part-time to help accommodate his care, even though she’d like to work more. In two decades of caring for her son, Cawdron has learned to understand what he means when he points at things to express what he wants – but this isn’t something anyone could walk into the house and pick up.

Cawdron is a spokesperson for the Complex Care Group, a network that connects the families of young people living with overlapping disabilities with high care needs. “There are lots of hidden costs,” she explains. “This is the reality for a lot of parents: emotionally, knowing you can’t get a break is huge. You need to be available all the time.” Respite care, allowing someone else to care for a disabled person so their primary caregivers can have a break, is vital for many families looking after people with high care needs. So Cawdron was one of many people shocked by a sudden announcement on March 18 from Whaikaha, the Ministry for Disabled People, announcing changes to how disabled people and carers can spend their disability support and equipment funding.

The date is etched into the minds of everyone I spoke to for this story. The revised purchasing rules meant that carers of disabled people could no longer provide koha for “voluntarily” provided support; instead, money for respite care had to be under employment arrangements. Travel costs for disabled people, whānau and/or persons providing support were excluded too, as was “self care”.

The announcement came via a Facebook post. It was midday on a Monday. There had been no consultation with disabled people and their carers, and the comments were promptly turned off. The changes were effective immediately.

An announcement, then the fallout

Penny Simmonds, then the minister holding the disability portfolio, said that the changes to the rules were necessary, as Whaikaha was was “within days” of running out of money – and some of the spending was going towards unnecessary luxuries for carers. “We’ve got such a broad criteria at the moment that the funding has also been used for massages, overseas travel, pedicures, haircuts,” she said at the time.

The webpage announcing the rules is a glimpse at the complex bureaucracy that disabled people and their carers have to navigate: alternatives to funding from Whaikaha include money available from the ministries of health, education and social development; grants and charitable donations; the Total Mobility transport scheme; and specialist services run by different government departments.

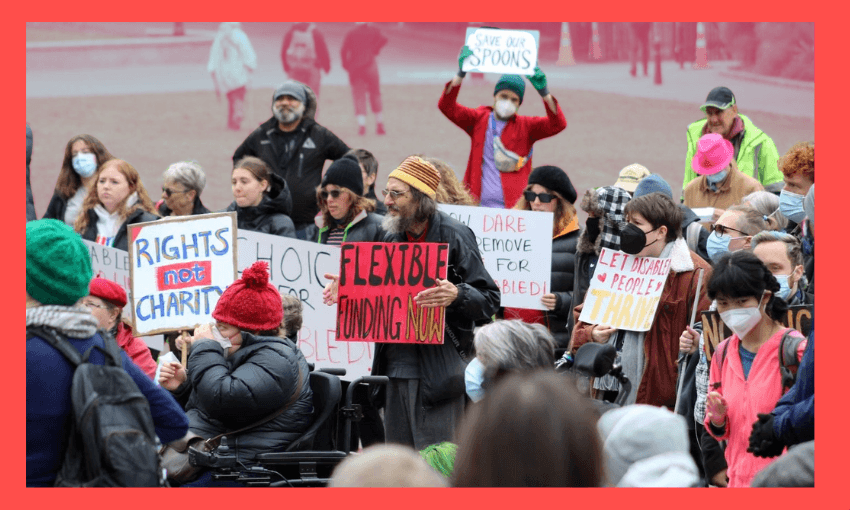

Facing criticism for the handling of the announcement, Simmonds and Whaikaha apologised for the way the changes had been communicated. Updated purchasing rules were released on April 24, but did little to ease the concerns of the disabled community, and Simmonds was eventually replaced by Louise Upston, who is the minister of social development and employment and sits within cabinet. Since then, there’s been widespread protest from organisations working across the disability sector with an open letter asking for reversals to the rule changes, better resourcing for disabled people across the government and greater involvement of disabled people and their whānau in decision-making signed by dozens of organisations.

Etta Bollinger, a spokesperson for Disabled People Against Cuts, says that directly after the changes were announced in March, it “felt like the world closed in”. The process of limited funding can make disabled people feel guilty. “Disabled people are acutely aware that we’re prioritised against each other,” they say. “In a fully funded system, an individual receiving support wouldn’t have to think about what is going on in the rest of the system.”

While the changes to the purchasing rules are particularly notable for their lack of engagement with the people most affected, Bollinger points out that just because a funding source doesn’t have the word “disability” in it doesn’t mean disabled people aren’t touched by it. The return of the $5 prescription fee from July 15 for those who don’t have Community Services Cards will be particularly expensive for the many disabled people who need regular medications. Disabled people without Total Mobility cards who use public transport have lost the half-price transport discount. Inaccessible – both financially and physically – housing puts disabled people at risk too. “Underfunding across the board impacts our ability to be part of society,” Bollinger says. “We need to push against [cuts] until disabled people have autonomy across their lives.”

There was a funding increase to Whaikaha in the budget on May 30, of $1.1bn over the next five years; however, the funding is contingent on the results of a review commissioned after the changes to individualised funding and respite care in June. “It’s really important funding – respite care comes out of that funding channel,” says Phoebe Eden-Mann, a policy analyst at CCS Disability Action. As far as she knows, the panel conducting the review are not disabled themselves, and haven’t (yet) consulted extensively with the disability sector. “If they’re not talking to us, how do they know what we want?” asks Colleen Brown, board chair at Disability Connect, an organisation that supports people with disabilities and their families.

There’s no timeline for when the results of the review might be released. “There are so many reviews – we don’t think we need another review,” Eden-Mann says. From the perspective of CCS Disability Action, the needs are well-established: more money is the solution, not more panels and reports.

What do changes to funding mean practically for disabled people and carers?

Nick Stoneman, a disability advocate living in Christchurch, lives with a number of visible and invisible disabilities. He currently receives funding for home help, managing domestic tasks that are difficult for him to do himself, and had been hoping to get individualised funding for other support, including treatment for pain in his hips caused by being in a full-time splint as a baby, but has been denied.

“There’s so much admin – I have to go to the doctor every three months,” Stoneman explains. “The process is very constrained – it could be simplified, but it won’t be. Because people have abused the system in the past, there’s no allowance for a high-trust model, so we’re viewed suspiciously.” He’s spent hours trying to navigate the support system for himself, as well as the clients he works with.

Cawdron feels exhausted when she contemplates how the purchasing rule changes have impacted her. “It’s a 24/7 job, so the only way of getting a break was to have that respite care. That’s been taken away by the restrictions.” She feels certain what the consequence of reduced respite care will be. “If the parents don’t get a break, they burn out, then kids end up in residential care – and residential care is truly expensive. It’s short-sighted.” Technically eligible for a disability allowance, Cawdron hasn’t bothered to apply – the $78.60 a week isn’t worth the hassle of the forms and receipts that getting the payment would require.

Over and over, people in the disability sector emphasise that it is the change to the flexibility of the respite care funding that will hurt people the most. The new funding rules don’t recognise the practical ways that families and communities look after disabled people. “Say you have whānau who know and understand your child and regularly visit from Hamilton to help look after them, they have to be employees – instead of being offered koha, which is a recognised way to acknowledge support,” Brown says. Relationships are affected: she knows many carers can get anxious about doing something as simple and ordinary as calling a friend, worrying that their loved ones are expecting to be asked to help out.

‘Stuck in limbo’

For Cawdron and Stoneman, as well as thousands of others within the disability sector, changes to disability funding make an immediate difference to their lives. But as well as practical details they need to negotiate, there’s an emotional consequence. The sense that vital funding can be eliminated at the whims of the distant government creates huge amounts of anxiety.

“It makes me feel like I’m a third-class citizen in my own country. Our needs are not valued, our voices aren’t heard, and people don’t want to understand what our needs are,” Stoneman says. Many disabled people would love to work, he says, but employers aren’t willing to understand how to accommodate those needs. “We’re stuck in limbo if we don’t have an understanding employer.”

Stoneman is also slowly paying off debt to MSD from income support payments, at a rate of $20 a week – another source of stress, especially when that money would make it easier to pay electricity or phone bills. “It would make such a huge difference if that debt could be wiped,” he says.

In the past 20 years since her son was born, Cawdron has heard lots of statements from different ministers, filled out more forms than she could count, been woken in the dark when her son needs her. But the suddenness of the announcement about the cuts, and the failure of the budget to change anything, felt like a “smack in the teeth”. “This has been the first time I felt completely devalued as a parent and carer by the public,” she says. “It’s completely discounted families – it’s made me feel like I’m not a person of any value.”

Her son will need care for the rest of his life: when she thinks of the future, she imagines more and more needs assessments, more and more forms. She finds it difficult to understand why disability funding is treated as if it adheres to the rules of supply and demand. “The funding is still capped, even though there are increasing numbers of people with disabilities.” One day, she and her husband might not be able to care for their son any more: what will happen then?

The changeability of what funding will be available in the future is particularly stressful. “People living complicated, difficult lives have this added layer of uncertainty, which has created a lot of anxiety,” Brown says. “The problem is that there is no plan for the disability community between governments.” Future governments could change the rules back, or add different funding categories, or reduce funding further, making it difficult to plan. “Disabled people and families muddle on as best they can, not knowing what comes next … we’re an inconvenience, that’s what we hear.”