The prisms of left vs right or capitalism vs socialism no longer explain New Zealand, writes Danyl Mclauchlan. Our nation is now divided into rent-seekers and those being fleeced.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

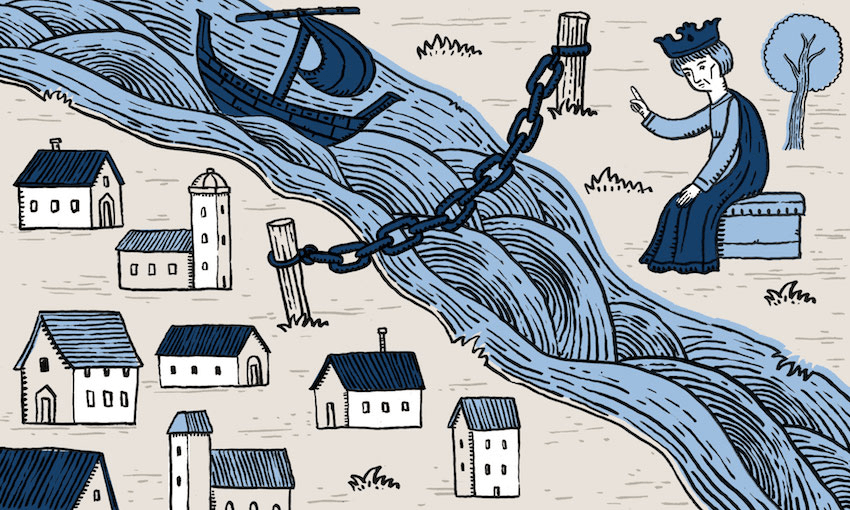

Original illustrations by Gary Venn

In December of 2021 New Zealand’s parliament passed an amendment to the Resource Management Act, liberalising building regulations across the nation’s urban centres. The building consent process has long been regarded as a major villain in the housing crisis. A PWC analysis estimated the new bill could add over 100,000 dwellings to the nation’s housing stock over the next eight years. The only party to oppose it was Act.

Which seems weird, right? Why would the liberal party oppose liberalising the housing market during a housing crisis? The reasons given were odd: Act didn’t like the process, the bill didn’t go far enough, it failed to simultaneously solve the problems with infrastructure funding; deregulation would “lead to chaos”, somehow. The arguments were both meaningless and unintentionally revealing, and they reminded me of Vaclav Havel’s famous greengrocer’s sign.

Back in 1978 the dissident Czech playwright published an essay called ‘The Power of the Powerless’. It featured a greengrocer in an eastern European socialist state, whose shop window displayed a sign reading: “Workers of the World, unite!” It had been distributed to him by the government, along with the onions and carrots, and he put it in the window, not because he agreed with the message but because a failure to do so might get him in trouble. It could be seen as a sign of disloyalty. The sign’s real message, Havel suggested, was “I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient”, but if it explicitly stated this then the greengrocer would feel ashamed, and might rebel, so:

“his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on its textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the greengrocer to say, ‘What’s wrong with the workers of the world uniting?’ Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. It hides them behind the facade of something high. And that something is ideology.”

Much of our political debate works the same way. It conceals something low behind something high. This essay is about what is being concealed, and for whom. It’s a followup to an essay I published last year, which argued that Thomas Piketty’s model of a “multi-elite party system” was a useful way to understand contemporary New Zealand politics. That we epitomised his description of a polity dominated by a “brahmin left” and “merchant right”: rival factions of the professional managerial class, and their loyal subalterns. The first essay focused on the brahmin left – currently the politically and culturally dominant clique – while this one looks at the merchant right, a group for which Act serves as the vanguard party.

I hope to make some members of this caste angry while persuading others to agree with me, and both of those are harder to do if I’m quoting Piketty all the time. “He’s just a socialist.” “He’s been debunked.” So instead I want to use the arguments advanced by James Robinson and Daron Acemoglu in their 2012 book Why Nations Fail, a sweeping political-historical-economic theory-of-everything that was a sensation among the intellectual right in much the same way Capital in the 21st Century became a leftwing cause celebre a few years later. Robinson and Acemoglu draw on concepts developed by the economist Gordon Tullock, and I like to think it’ll be harder for people on the right to protest that Daron Amoceglu has been debunked, or that “Tullock was a socialist”. But also, full disclosure, I prefer Why Nations Fail and its follow-up, The Narrow Corridor, to Piketty’s books which are, frankly, very long and often hard to read. And, spoiler alert, I think they end up in a place that isn’t a million miles away from Piketty.

Why do nations fail? According to Acemoglu et al much of modern state failure can be described by two words: rent seeking. This is a term from the early days of economic theory – it’s in Ricardo and Smith – but it fell out of vogue in the late 19th and most of the 20th century, resurfacing in the 80s and becoming a focus of intense interest in the last two decades. Here’s an often cited definition from Robert Shiller back in 2013:

“The classic example of rent-seeking is that of a feudal lord who installs a chain across a river that flows through his land and then hires a collector to charge passing boats a fee (or rent of the section of the river for a few minutes) to lower the chain. There is nothing productive about the chain or the collector. The lord has made no improvements to the river and is helping nobody in any way, directly or indirectly, except himself. All he is doing is finding a way to make money from something that used to be free.”

We can make a few points about the lord, his river and rent-seeking in general. The first is: this is how traditional libertarians (and Marxists) conceive of a capitalist state: the lord owns the land, he can do what he wants with it; the government exists to enforce his property rights and the private contracts he makes with his customers. But, Acemoglu et al ask, is this really capitalism? Because there’s no market: if you have to transport anything via that river he can and will charge you whatever he likes, so any profits you might make will be captured by him. The lord is bad for every business except his own. The second is that the lord is strongly incentivised to use his political power to prevent the emergence of a competitive market: a road that goes around his land, say, or any new technologies that might threaten his rent. The third is that the best – and often only – way to solve these problems is with the intervention of the state. Maybe the government mandates a maximum charge, or builds a road around the lord’s land, or funds research into telecommunications technologies, or even nationalises the river. Government can be, contra Reagan, Hayek etc, the solution to the problem, so long as it isn’t controlled by the lord. Which it usually is – a phenomenon Tullock refers to as “regulatory capture”.

If rent-seeking is a deep problem, if it prevents the emergence of free markets, equality of opportunity, entrepreneurship, economic growth, creative destruction and all the things that advocates for capitalism are supposed to believe in, then the classical liberal case for a minimal state, loses much of its coherence. Because the state creates the market. But the state is not an unconditional good: it also breaks the market under conditions of regulatory capture. So what matters for Amoceglu et al is the nature of its intervention. Does it incentivise rent-seeking and a low growth, extractive economy, because its institutions have been captured by elites? Or does it facilitate functioning markets, innovation and a productive, redistributive economy because the political system is inclusive and responsive to its citizens?

This might all sound very theoretical: a hypothetical lord chaining an imaginary river. What does it have to do with New Zealand? The most glaring answer is housing. Because there’s a difference between economic rent as described by Shiller, above, and the rent you pay your landlord to live in a house they own. A house is valuable: it’s reasonable to charge people to live in one. In a competitive market if you charge them too much they’ll move someplace else. If there’s increased demand for houses someone will build them. But if the population increases and the landlords use zoning laws to prevent anyone from developing new properties, and then raise their rents because there’s nowhere else for their tenants to go, then that additional rent is all economic rent.

The landlords aren’t doing anything useful for that extra money. They’re just using political power to extract value from the productive economy, same as the lord chaining his river. And when the artificial scarcity of housing drives up property values then all homeowners extract rent from people trying to enter the market, who have to pay inflated prices. The quality of the housing hasn’t gone up. (The quality of our housing stock is mostly terrible.) It just costs more.

In May 2021 the economist Geoff Bertram published an article in Policy Quarterly on the subject of regulatory capture in New Zealand markets. Drawing on Acemoglu, Robinson and Tullock, he revisits the very familiar subject of New Zealand’s neoliberal era: the sweeping political reforms of the 80s and 90s. Both the left and right have deeply ingrained narratives about this period in our history. Either a socialist utopia was transformed into a capitalist hell, or a socialist dystopia was liberated into a free market paradise, depending on which version you subscribe to.

But, Bertram points out, if you regard rent-seeking as something very distinct from free market capitalism, something that destroys competition, growth and innovation, it’s hard to see much capitalism emerging as a result of the neoliberal revolution. The privatisation and sale of state-owned monopolies – power, telecommunications, rail etc – didn’t create markets. Instead they created private sector monopolies.

Bertram notes:

“A striking feature of the New Zealand privatisations of 1987-96 was precisely the domination of value extraction over value creation. Typically, the private ‘insider’ purchasers used leveraged buy-out tactics to secure control, then extracted cash gains and exited, in several cases leaving the enterprises they had sold in a parlous state requiring taxpayer-funded bailouts.”

Instead of a capitalist economy, Bertram argues that New Zealand became – and largely remains – an economy predicated on rent-seeking, in which most major markets are deliberately broken so that the dominant actors can extract value without proper competition. There have been a few steps to remedy this, notably the unbundling of Telecom by the fifth Labour government, when the price-gouging, and anti-competitive practices of the monopoly became too economically destructive to ignore. It’s worth noting that Roderick Deane, a former Reserve Bank official and one of the intellectual architects of the neoliberal reforms, became chief executive of Telecom, and was celebrated by the business community as the “CEO of the decade” in 1999, but stood down when his monopoly was broken up. And since then we’ve seen tremendous growth in the ICT sector – because the state intervened. Bertram summarises the legacy of Deane, Roger Douglas, Ruth Richardson et al:

“The sweeping institutional changes imposed by successive New Zealand governments between 1984 and 1999, and consolidated thereafter, have left in their wake a paradoxical situation. The changes were motivated and justified by ideas drawn from the economic theories of public choice, rent-seeking and regulatory capture advanced by the Virginia and Chicago schools of economics and law, and were ostensibly designed to free New Zealand from the ills diagnosed by those schools of thought in the US. Yet the effect of the changes was not so much to eliminate pre-existing problems of capture and rentseeking as to reinvent New Zealand as a case study of those pathologies in action, only under different management.”

The main thing that changed in the 80s and 90s was not a transition from “socialism” to capitalism or neoliberalism, but a transition from an extractive, low productivity economy dominated by the state to an even less accountable, more ruthless form of corporate rent-seeking with even lower growth. In my last essay I described the covert agenda of New Zealand’s brahmin left as “upwardly redistributive socialism”, and if we view our merchant right through the lens of rent-seeking and regulatory capture, their agenda can best be described as “private sector anticapitalism”.

Shortly after she became prime minister, Jacinda Ardern told a journalist she thought the nation’s homelessness problem was a “blatant failure” of capitalism (five years on it is now significantly worse). A few years later Chris Finlayson, who had been attorney general under the Key government, opposed the deregulation of Wellington’s housing market as “Stalinist”. John Key attacked Labour’s child-based tax credit as “communism by stealth”; Energy minister Megan Woods blamed “the market” for a power blackout caused by her own state-owned enterprise and industry regulator. Last week, National party leader Chris Luxon delivered a state of the nation speech praising the power of free markets, adding:

“I remember sitting in a modest Moscow flat with a couple in their late 40s on a dark and snowy afternoon. It couldn’t have been clearer that socialism – in terms of government control of everyday life and lack of rewards for hard work – had abjectly failed and actually created misery.”

This style of discourse – capitalism, socialism, neoliberalism, communism, Stalinism, the nanny state – is ubiquitous among both the brahmin left and merchant right. And it conceals something low behind something high, creating the pretence that the rent-seeking strategies of these rival factions is a clash of values and ideals. It conceals our elites’ motives from themselves, and from their subordinates: those who aspire to elite status and so consume and regurgitate their ideology – but whose material interests are often in direct conflict with them.

When Luxon became leader of the National Party he talked about using his business skills to turn the country around. “I have built a career out of reversing the fortunes of underperforming companies and I’ll bring that real-world experience to this role.” It’s the same message John Key used to sell his own leadership back in 2008. Given Luxon’s obvious talents and the vast amount of money he earned as CEO of Air New Zealand, you like to think he’d put his capital to work investing in new or struggling businesses, but of course it’s invested in property. One media report estimated that his portfolio earns about $90,000 a week in capital gains. And he’d be foolish to do anything else, since capitalism is about risk while our property sector is almost entirely risk free. To really reverse our underperformance Luxon would have to transform New Zealand into an economy where someone in his position was incentivised to use his skills and risk his money to make those kinds of gains.

The second largest line item in the government’s welfare spend is the accommodation supplement (superannuation is the largest). If you factor in emergency housing grants it costs about two billion dollars a year, nearly doubling over the last three years. And this sounds like it should be a progressive policy because it’s helping the poorest people in the country meet their living costs. But in reality it functions as a gigantic wealth transfer to the rich, who own the houses and motels. The US political scientist Steven Teles calls this “cost disease socialism”: you take a sector broken by regulatory capture and rent-seeking, and instead of solving those problems the state pours the public’s money into it. It’s a mind-blowingly expensive way to look like you’re doing something without accomplishing anything or helping anyone. Except the landlords. Or, in the case of power prices and the government’s winter energy subsidies, the power companies which are mostly majority owned by the state itself. The public subsidises the state’s own rent-seeking.

The government is building new state homes, and shifting some of the bottlenecks in development and construction. But building materials in New Zealand are extremely expensive: 30% higher than in Australia, which is a much wealthier country than us. The Commerce Commission has begun an investigation into why this is, but there’s widespread suspicion that the market is (naturally) broken. Carter Holt Harvey – owned by Graeme Hart, the wealthiest man in New Zealand – controls about half of the timber sector; Fletchers enjoys near total dominance of concrete and plasterboard. The Commerce Commission is only funded and empowered to investigate one industry at a time.

On Tuesday, the commission released its report on the supermarket duopoly. Two numbers captured media attention: that New Zealand supermarkets were enjoying excess profits of about a million dollars a day, and that over the last 20 years they’ve made extensive use of exclusivity clauses and “land covenants” to prevent competitors from entering the market. And this lack of proper competition allows the duopoly to transfer cost and risk onto their suppliers. This should sound very familiar; it’s the lord chaining the river, extracting rent, crushing the rest of the productive economy. And the week this report was released the two large parties were arguing about tax cuts and welfare dependency, even though there’s no tax break or welfare increase that could do more for either families or small businesses than breaking the duopoly.

I began my previous essay with Thomas Piketty’s observation that 21st century democratic politics is transitioning into a contest between parties dominated by business and institutional elites, and I’ve tried to sketch out what his brahmin left and merchant right look like in New Zealand (the inequality researcher Max Rashbrooke describes them as the Kelburn left and Remuera right). Both of them are predominantly rent-seeking, exerting political or managerial control to extract value from the economy rather than create it.

And the factions are co-dependent. The inadequacies of the public sector, grotesquely bloated and overmanaged while simultaneously hollowed out and underpowered, justify the merchant right’s arguments that the state shouldn’t interfere in the market. Which leaves us with deliberately broken markets that the brahmin left convince themselves they can fix via the expansion of the central administrative state: more ministries, commissions, departments, crown entities, regulatory agencies, more fire hoses of money to consultancies and outsourced private service providers.

What I’m trying to describe here isn’t a group of bad people but rather a system; a culture, a set of terrible policies, bad incentives and ideological self-justifications. If you get rid of the managerial class, somehow, their replacements will behave the same way, probably with less competence. Most revolutions fail, Acemoglu and Robinson argue, because they change the management without changing the underlying system. One group of rent-seekers simply gives way to another. Senior treasury officials move to the private sector; Lenin becomes the tsar.

Havel tells us that the power of the powerless is to recognise where the true power in our society lies, how it is used, how it conceals and justifies itself. “Ideology,” he wrote, “has a natural tendency to disengage itself from reality, to create a world of appearances, to become ritual. Increasingly, the virtue of the ritual becomes more important than the reality hidden behind it.”

The goal is to change the system, which begins with seeing it. Most people who follow politics do so the same way sports fans follow a game: you cheer your side and hiss at their opponents. I want people to stop looking at the teams or individuals and see these systems at work: “private-sector anticapitalism”; “upwardly redistributive socialism”; regulatory capture. Rent-seeking. Because I think that once you start looking you’ll see them everywhere. And you’ll see that both factions ritualistically manufacture ideology about socialism or revolution, freedom or capitalism, not to deceive the rest of us but primarily to delude themselves, and so conceal the true foundations of our politics, the low behind the high.

Love The Sunday Essay series? Be sure to check out The Sunday Essay postcard set over in The Spinoff shop. The set includes 10 original illustrations from the series with insight from the artists.