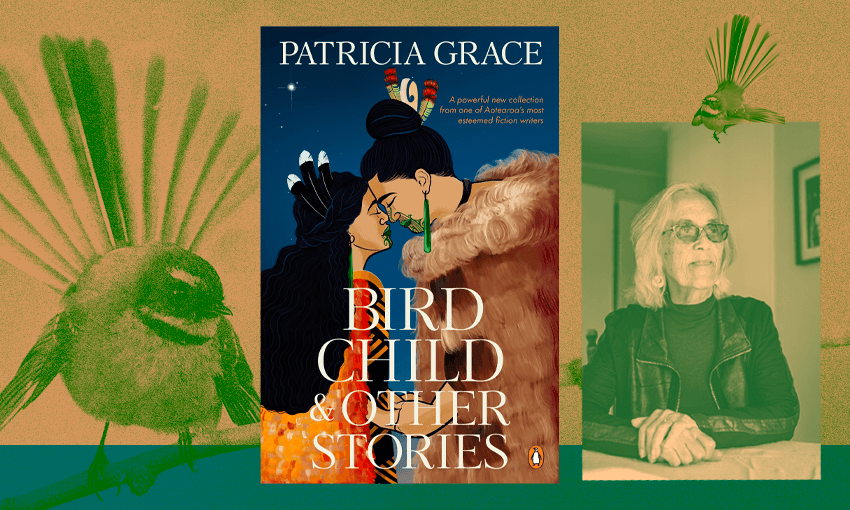

Rangimarie Sophie Jolley reviews the new short story collection from Patricia Grace.

It’s hard to have idols. For many of us, Patricia Grace sits at the peak of our literary maunga, shrouded by a misty horizon and a standard of excellence to her pen that many seek to emulate. Grace is unmatched in her observation of the human condition. Her ability to completely immerse the reader in character and then gently guide them through inner machinations, both simple and complex, has shaped the way stories are told in Aotearoa.

I met with Patricia to discuss this skill and how it came to serve the stories collected in her latest collection, Bird Child & Other Stories. The book is a collection of three parts. The first an ode to mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge and worldview), using stories told by our pre-colonial ancestors to send us deep into our imaginations. The second part is a collection of new and old short stories centred around the character Mereana, telling tales of war-time Wellington and the fraught relationships forged within the urban drift. The third is a collection of new short stories (bar one revised edition) reflecting our modern day lives back to us.

In a bustling Tītahi Bay cafe, we sat and discussed the power of observation. When asked about her process for deciding what she wants to write and the plethora of ways we can do that, Grace insists that she only wants to “write what I want to write, the way I want to do it”.

Part One: Pūrākau

Most writers are, by nature, avid people watchers – inclined to daydream the morsels of a stranger’s life. Often, we colour our observations with the details we see hinted by their body language, motivations betrayed by the worn frown lines on a worry-warts face, freedom flouncing at the hem of a summer dress.

The same skill of observation is applied to our natural world. In reading Grace’s work, I’ve often found myself wondering just how much time she spends watching and listening to birds. This was particularly acute reading the title story, Bird Child, through which the stories of an unborn child and a Kākā bird are entwined.

Throughout the story, Grace uses English language prose to reflect back the language of mōteatea, waiata and oriori (chanted poem/lament, song and lullaby). She admits to being captivated by the language in oriori in particular, as a mode of orating strong emotional language:

Go to sleep

My cachet of sweet smelling leaves

Listen to my song

My adornment of pounamu

Sleep…

Her command of the English language allows an insight into the often janky bridge between word-worlds. Each word is a hint at the missing link between the natural world reflected in te reo Māori and the Anglo-Saxon-Latin-German-amalgam that is te reo Pākehā where, at times, no translation will suffice.

Bird Child exemplifies the ways in which Māori phraseology and ideology can be used in a fictional English-language context to blur the real and surreal together. The English equivalent was accurate enough to provide insight, but far removed enough to protect the mātauranga Māori within.

An essential third character in the story is the ngahere itself – the natural forest / bush terrain that the hapū navigate as they seek safety and shelter for the active labour of the mother. The “wordless trees” of human respite become the fruitful cacophony of birdlife returned, reminding us of the plethora of symbiotic relationships with nature so fundamental to our Māori world view.

From this viewpoint we delve into the tale of one of the most well-known characters in te ao Māori – the fire maiden, Mahuika. Having had her story written many times, often by men, Mahuika is often construed as a kuia of poor judgement. However, in this modern re-telling, she is given a new life. So too are her companions, the story aptly being named Mahiuka et al.

Grace considered the cast of this story very carefully in her reconstruction, asking herself who might compliment this new version. Through the Pūkeko and Tīrariaka (Pīwaiwaka/Pīwakaka/Pīrairaka) we are given insight into this oft maligned female deity’s spunk, wisdom and multi-dimensional character. It was also refreshing to read the forgotten description of Māui as a deformed, misshapen creature of myth.

With her motley crew of manu, Mahuika (spoiler alert!) doesn’t remain frozen in the moment of her story during which Maui appears. This is not just refreshing, but revolutionary and an absolutely necessary reflection of the type of character analysis that’s challenging Māori storytellers across the board. Grace admits that she was excited by the challenge, stating “I just want to write a good story, but my main interest is a good character”.

The Sun and Moon also have new life breathed into them. In The Sun’s Marbles, we see the perpetual tension of the relationship between Tama-nui-i-te-Rā (the sun) and humanity explored. There’s a bittersweet tone to this short story, a parental lament to the regretful ponderings of parents who observe the faults of their children: “Had Sky become too distant? Had Earth been too overcompensating?”

In The Unremembered we are given a chance to meet the fabled ancestor Rona anew. Rona and The Moon’s relationship has been told through waiata and story for generations as a warning to never curse the kaitiaki who look over us. In this retelling, we get into the ngako (essence) of the relationship between the two. This is played out in the tension of their debate over the foibles of humanity. Their dialogue shines a necessary light on the consequences of climate change and the fickle memory of human history.

Part Two: Mereana

Anyone familiar with Grace’s autobiography, From the Centre: A writer’s life, will recognise some of the landscape against which the stories of the title character, Mereana, is depicted. The collection follows her adolescent exploration of the changing world. She discovers the wider-world through the events of World War Two. As is Grace’s talent, the entire collection serves to build bridges between all of the contexts Mereana seeks to understand.

There exists a tension between the war-obsessed adult world, and the sought after comfort of the very Māori world left behind in the urban drift. When the Lights Go On Again All Over the World introduces us to Mereana’s on-going attempt to make sense of this expanding worldview. Living with shutters on curtains and lights off all over the house-littered hills, Mereana’s imagination frequently wanders to the cause of all this darkness: “The enemy was ‘overseas’ in another land and soldiers went to fight against it. But what were enemies?”

In Departure, we’re given insight into some of the lighter aspects of Mereana’s life. Though her fathers enlistment insights a fresh slew of emotions, there are also familiar comforts. These take the form of freshly shaved pencil stubs and precious lined paper to build bridges between her and her deployed fathers world. There is also the introduction of the ever-comforting presence of Aunty Mereana (her namesake).

Aunty Mereana’s role throughout the young Mereana’s life is a familiar one to many – she exists as a lifesource between the suburban, Pākehā world and the often rural Māori home of the wider whānau and hapū. When asked about the decisions about which stories to include in the revised collection, and the temptation to change them, Grace indicates that the Mereana stories “belong to a certain time and place, but I stand by them. I can look back on them with pride”.

This is a particularly delightful and comforting sentiment when reading stories such as The Lamp, where the youthful ignorance of the relationship between confidence and guilt is explored. The character of Mereana is really revealed here, someone seeking to make sense of the ever changing rules of the adult world and finding that sometimes, no sense can be found.

As is Grace’s style, there is a comfort to be found amongst all heartaches. While Mereana longs for her fathers safe return from the war, she navigates the horrendous forms of racism plaguing her community. In Going for the Bread, Mereana suffers at the hands of two racist teens, an act that adds a grim shadow to her already darkened world.

However, again, it’s the heralding of home that lifts our heroine out of this harshness. Mereana’s mother is a key component in providing this comfort – she brings a quiet and courageous strength to Mereana’s turbulent life. One that is supported by Aunty Mereana and the pā (home) of her kaumātua, Nini and Paa.

The Uncles of this Pā life are a carousel of familiar characters – Uncle Kepa with his wild tales gives the kids an insight into who their fathers might be when they come home, Uncle Barney a man of perpetual movement (every whānau has one!), the “soldier uncles” a representation of the child-like knowing that comes with being part of such a big, unified group.

Throughout the Mereana stories, every mention of this pā life is so… consolitary. It’s both a privilege and kind of magical to step into the world of our grandparents to witness the people and places they often left behind. For many of us who grow up to be intergenerational products of the urban drift / Māori who offer flickers of a flame back to those who remain ahi kaa, these types of stories are a treasure we can hold on to.

Part three: The New Ones

This collection of new stories allows access to some fantastic contemporary characters. Their modern-day tribulations are consistently juxtaposed by the classic whims of human instinct. The opening line of the first story, Green Dress, is an enthralling capture – “These words, which are barred behind my clamped down teeth…are not incarcerated there because of what I wore to my wedding.”

It’s this style of punch and wit that defines the central characters of each story – some strong, some resentful, others navigating the depths of grief. Matariki All Stars explores these all in one, where a single father is working through the remains of his life without his wife, whilst trying to raise his daughters. This story was a stand out, having multiple moments familiar to young parents, single parents, sisters and oldest daughters littered throughout.

The same can be said of Thunder, where the children of single parents struggling to “stay above the breadline” are brought together. As always, it’s the sense of community and whānau that demonstrate privilege in these contexts. This familiarity of whānau is a concept also explored in Seeing Red, where the struggles of a modern-day bureaucrat burdened by the unofficial cultural demands of his role begin to take their toll – something many Māori can relate to.

The Machine is a revised edition of the story initially published in 1972. It’s the haunting tale of an adult daughter trapped in her mothers life, where we witness the burgeoning yearnings for one of her own. Although it takes place decades previously, there’s a familiarity to the backdrop of the Notebook Factory where she works. I can’t help but wonder if it’s an homage to the writing tools of yesteryear – the pencil stubs, knives to sharpen, stapled paper notebooks and the smell of fresh lined sheets waiting for stories to be told.

Alongside this recurring theme is another, one never far from Grace’s pen. In The Parson Who Thought He or She was a Bishop we swoop further into the relationship birds facilitate between life, death and the inevitable arrival of age. This is also revealed in the closing story, Whakarongo, which serves as the ultimate ode to those who remained in service to our communities during the pandemic.

When asked about the potential familiarities between the characters and settings in her stories, Grace responds: “A character might be built up of several people that you’ve observed…or are.” This ability to weave all the threads of knowing together into a succinct story with a strong character is something all writers aim for.

Grace closes the entire book with a haunting but hopeful whisper about the feathered creatures that inspire her observations. It’s the perfect precious morsel to leave on ones satiated literary palette, from one of the most talented wordweavers of our time: “Listen to the birds”.

Bird Child & Other Stories by Patricia Grace (Penguin, $37) is available to purchase from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.