Eileen Merriman has whipped out three fine novels for young adults since debuting in 2017. Moonlight Sonata is her first crack at writing for adults. In this first chapter Merriman sets up a beatific family holiday – New Year’s, the beach, deckchairs and drinks – and injects a dose of abject wrongness.

They see the fish on their first day, laid bare on the tideline. The seagulls have nearly picked the bones clean already.

Noah turns, his calico fringe flopping into his eyes. ‘Must have been dumped overboard by fishermen. What do you think?’

‘I’d say so.’ Molly glances at her husband for corroboration, but Richard is already striding ahead, putting as much distance between the house and himself as possible.

‘They’re snapper,’ she says. ‘Maybe Uncle Joe will take you out fishing tomorrow, if you’re lucky.’

‘Sweet.’ Noah pulls his t-shirt over his head. ‘Coming for a swim?’

‘Soon.’ Molly watches her only child run into the waves, although, at the age of seventeen, he’s more a curious mixture of half-boy half-man. There’s a lightness in his movement she hasn’t seen in months.

She prods one of the fish skeletons with her toe; turns and looks up at the house on the hill. Three, maybe four figures are assembled on the balcony. A peal of laughter drifts towards her. Sighing, she looks back at the fish. Coming home is like this. It strips her bare. You are nothing. You . . .

That afternoon, Molly sits on the front balcony with her mother, drinking coffee even though sweat is trickling into every little crevice of her body. The air is thick and sultry, quite different from the dry slap of the desert-like air in Melbourne.

‘They shouldn’t be long now,’ Hazel says. ‘Austin texted half an hour ago to say they were leaving Whangarei. He asked if we had real coffee.’

Molly smiles. ‘Did you tell him about Richard’s supply?’ Her husband had brought his stovetop coffee maker, along with freshly ground coffee from their local café in Melbourne.

Hazel snorted. ‘People used to be satisfied with Gregg’s instant.’

‘And now they need it to have passed through civets before anyone will drink it.’ Richard sits in the deckchair beside Molly, his laptop under his arm.

Molly frowns. ‘Don’t tell me you’re doing work already?’ ‘It’s not work, exactly,’ Richard says, flipping the lid open. Some things never change. No, most things never change. ‘So, how’s Melbourne?’ her mother asks.

‘We like it,’ Molly says. ‘Lots more research opportunities. Everyone’s really friendly.’ She won’t tell her mother about the gnawing homesickness that hit her three months in, a feeling she’s not sure will ever fully abate. Richard, already engrossed in answering emails, just nods vaguely.

Hazel dips a gingernut into her mug. ‘They say it’s only a matter of time before there’s a major terrorist attack over there.’

‘Meanwhile, for another of your children, that’s a daily occurrence,’ Molly says, an all-too-familiar irritation creeping up on her, like a migraine aura. ‘When was Joe’s plane getting in, anyway?’

‘This morning.’ Her mother sips on her coffee. ‘I think he knows how to handle himself.’

‘I don’t imagine anyone knows how to handle themselves in the Middle East,’ Molly says, but her mother has stopped listening, as usual. Hearing the hum of an engine, Molly rises to her feet and sees a white SUV nudging into the driveway.

‘There’s Ants et al.’ Her second-eldest brother, with his wife and three kids, whom the rest of the family jokingly call the brunettes, as they are the only cousins not to have inherited the Mortimer blonde locks. Austin is the first to jump out, as bright as ever in his fire-red shorts, lime green t-shirt and cowboy hat. Obviously his first year as an official teenager hasn’t dulled his dress sense.

‘Wow,’ Molly says in a low voice, when the next teenager climbs out. ‘She’s grown.’ Lola looks up, twisting her ponytail.

‘Hey,’ she says, her eyes flicking around the yard. Looking for her cousins, no doubt.

‘They’re at the beach,’ Molly says.

‘Yes, but don’t you want to come in and open your Christmas presents first?’ Hazel calls after her, but Lola has already taken off down the road.

‘Hey, Aunt Molly.’ Tom, her brother’s eldest child, squints up at her. ‘Who else is up there with you? Oh, hi, Nana.’

‘Gosh, you’ve all turned into giants,’ Molly says. ‘Oh hell, that was an old-person thing to say, wasn’t it?’

‘A lot can happen in two years,’ her mother says behind her, never one to resist a dig at Molly’s absence last summer.

Obviously moving countries is no excuse.

‘Old enough to vote now,’ Ants says, with an easy grin. Molly’s sister-in-law frowns after Lola, who has long since disappeared around the corner. ‘Trust her to take off without checking her blood sugar,’ Kiri says. ‘Honestly, you’d think she was five, not fifteen.’

‘Almost sixteen,’ Ants says. ‘Where’s your giant, Molly?’

‘At the beach, of course. Can’t keep him away.’

Behind her, her mother says, ‘I don’t blame him, do you?’

Ignoring her, Molly moves inside, cool shade washing over her parched skin. It’s not long before Ants has followed her into the lounge. After dumping a suitcase in the middle of the room, he plants his hands on his hips.

‘Got a hug for your favourite brother?’

Molly moves forward. ‘It’s good to see you,’ she says, holding him tight.

Ants steps back. ‘You cut your hair short.’

‘Oh. Yeah.’ Molly tucks a strand behind her ear. ‘All I ever did was tie it up.’

‘Looks good,’ he says, turning to the photo of their father on the mantelpiece.

Out of all of them, her middle brother had taken their father’s death the hardest — although sometimes Molly resents her brothers for the extra years they had with their father. Six years of exile in Christchurch with her mother; Molly doesn’t know if she’ll ever really forgive her for that.

Ants looks back at her. ‘Joe here yet?’ he asks, because they both know who the favourite brother really is.

‘No,’ she says. ‘But he shouldn’t be too far away.’ A twelve-year-old version of Molly is turning somersaults in her stomach.

Not too far away is . . . too far away.

It’s two years since Molly last saw Joe. Two years, and now her twin might be here in the next two minutes, less even. Her skin feels tight, and she can hear her heartbeat, their heartbeat, resonating in the depths of her hindbrain.

She and Joe aren’t identical twins, of course, but they orbited each other for nine months, like a pair of moons. She feels his gravitational pull even when he’s across the other side of the world.

Molly can barely sit still. Perhaps that’s why she snaps at Richard when he says, ‘What do you think about heading to Auckland on Tuesday instead of Wednesday?’

‘We said we’d spend a week here.’ Molly is sitting on the double bed in one of the spare rooms, the same bed she used to sleep in as a teenager. On the windowsill, waiting for the vacuum cleaner, is the usual summer line-up of dead flies, one still in the throes of dying. The brown-patterned wallpaper beneath the sill is peeling — the same wallpaper she’d picked at the night before she left home for good. Pinkie swears are forever, Lolly. Don’t forget. The voice is so clear she sucks in her breath, blinks to see Richard staring at her from his spot in the doorway.

‘Six days is practically a week,’ he says. ‘You and your mum will be at each other’s throats by then anyway, won’t you?’

‘That’s not the point. I still want to see the rest of the family. It’s so much harder now we’re in Melbourne. What are you busting a gut to get back to Auckland for anyway?’

His gaze steady, Richard says, ‘I want to catch up with Jeff before he heads down to the Coromandel.’

Anger flashes behind her eyes. ‘I thought we were having a holiday.’

‘He wants to have a quick chat about a review we’re collaborating on. What’s the big deal?’

Molly slides off the bed, walks down the hallway and onto the back balcony. The air is thick, cloying. She grips the railing, trying to breathe, to calm down.

‘OK, look, why don’t I drive down and come back for you?’ Richard’s right behind her, still clutching his laptop. She feels like grabbing the sodding thing off him and flinging it onto the concrete below.

Molly grits her teeth. ‘I’d appreciate your support, Richard.’

‘Why me, when you’ve got Joe?’

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ she says, her voice rising, then dropping when she sees Lola heading up the steps, her wet hair twisted on top of her head. Lola glances at her, quickly, and then away.

‘I don’t see why this has to be such a big deal,’ Richard says, once Lola has disappeared inside.

‘No,’ Molly says, her voice low. ‘That’s obvious.’ Either he doesn’t see or doesn’t care about the fracture lines running through their marriage. Richard just shakes his head at her and returns inside.

Trying to slow her breathing, Molly watches Tom and Noah erecting their tents on the back lawn below. Noah has placed his tent near the back fence, the entrance facing the shed. Tom is erecting his tent closer to the magnolia tree in the opposite corner, presumably to get some shade. A year apart, Tom and Noah are a similar height, although Tom is more solidly built, while Noah is lean and muscly, a swimmer rather than a rugby player. If she squints, Noah looks just like Joe did as a teenager. The realisation makes the inside of her chest feel scooped out.

Noah looks up. ‘You OK there, Mum?’

Molly swallows. ‘All good. Make sure you zip up the fly, keep the bugs out.’

‘I know,’ he says.

Richard has always been such a stickler for setting up everything correctly. Molly turns and walks into the kitchen. Kiri is assembling a cheese platter, her dark hair falling in waves around her chin, while Lola gulps on a glass of water. Funny how children often resemble their parents more and more as they get older.

Shutting the thought down before it can assume its full form, Molly leans against the doorframe.

‘Lola, I haven’t had a chance to say a proper hello to you yet,’ she says, forcing a smile.

Smiling back, her niece lunges forward to hug Molly, the fruity scent of her shampoo wafting before her.

‘So, how are things?’ Molly asks, once she and Lola are in the pine-scented lounge.

Molly takes a seat in the armchair next to the Christmas tree. It’s two days since Christmas, but there are still plenty of gifts waiting to be opened by the newly arrived family members.

‘Are you still playing cricket?’

‘I’m in the first eleven at school. And in the under-seventeen team for North Shore.’ Lola flops onto the couch.

Richard has retreated to an armchair near the window, his head buried in his laptop. Molly turns her eyes away from him.

‘Dad says you’re a professor now,’ Lola says.

‘An associate professor,’ Molly corrects, noticing the Christmas fairy her mother has been placing on top of the tree for as long as she can remember. The fairy has a silver-white dress with wings, and improbably long eyelashes. I brought her back from Vienna when I was twenty years old, her mother always says. I’d love to go back, one day.

Lola crosses her legs beneath her. ‘That’s still good, isn’t it?’

Molly smiles. ‘It’s still good.’

‘Is it true you’re trying to find a cure for cancer?’

‘Well, one specific cancer,’ Molly says. ‘There could never be one cure for all cancers, I don’t think. There are so many different pathways.’

Lola wrinkles her nose. ‘That sounds really hard.’

‘It is. But we’re getting closer.’ Catching her distorted reflection in a silver bauble, Molly sets it swinging. ‘Are you still learning the piano?’

Her niece shakes her head. ‘Not anymore. I’ve got so much else on, you know?’

‘Yes,’ Molly says, her smile fading. ‘I know.’

I worked my fingers to the bone for you. All those years of practice, wasted. Sully wanders in from the kitchen, holding a bottle-opener.

‘Hey, Sis, can I interest you in a beer?’

‘That would be lovely.’ Molly watches her eldest brother flip the cap off a bottle of beer.

‘Cheers.’ Sully’s hair has receded almost back to the crown of his head, mimicking the outgoing tide. He’s still Sully, though. Constant, a rock. Sully-who-stayed, while the rest of them ran away. Even Chloe, Sully’s wife, left fourteen months ago. No one misses her that much.

‘Cheers,’ Molly echoes, ignoring Richard’s sideways look.

He hates it when she drinks beer. She tips the bottle back, the amber bubbles fizzing across her tongue. I’ve got three brothers, Rich. Guess there’ll always be a bit of tomboy in me.

‘Rich?’ Sully asks.

‘No thanks, bit early for me,’ Richard says in a measured tone.

Sully smirks at Molly. She ignores him.

‘Would you like a coffee instead?’ Austin is standing in the doorway, holding Richard’s coffee pot and a Bluetooth speaker.

‘Love one,’ Richard says, at the same time as Lola says, ‘Can we please listen to someone other than Sia?’

Austin juts his jaw at his sister. ‘Beyoncé called her a genius.’

‘Yeah, but there are only so many thousand times I can listen to—’ Lola begins, before Austin charges past her and onto the balcony.

Molly feels a rush inside her gut, the same whoosh she used to feel when she rode the rollercoaster at Rainbow’s End. She follows Lola and Austin outside.

‘Joey!’ Ants is striding across the lawn to meet their youngest brother. Joe isn’t looking at him. His head is swivelling, as if he’s lost something. Tipping his head back, he looks up at the balcony, his eyes locking on hers.

It’s always a shock, seeing her twin again — as though the cells in her body have been milling around for the past two years, Brownian motion, and are now humming and aligned toward him.

‘Hey,’ Joe says, and then he’s trying to hug all the members of the extended family at once. They are swarming over him like bees. The favourite uncle, the favourite brother, the favourite son. She should resent him. She doesn’t. She loves him just as much as they do.

No. More than that.

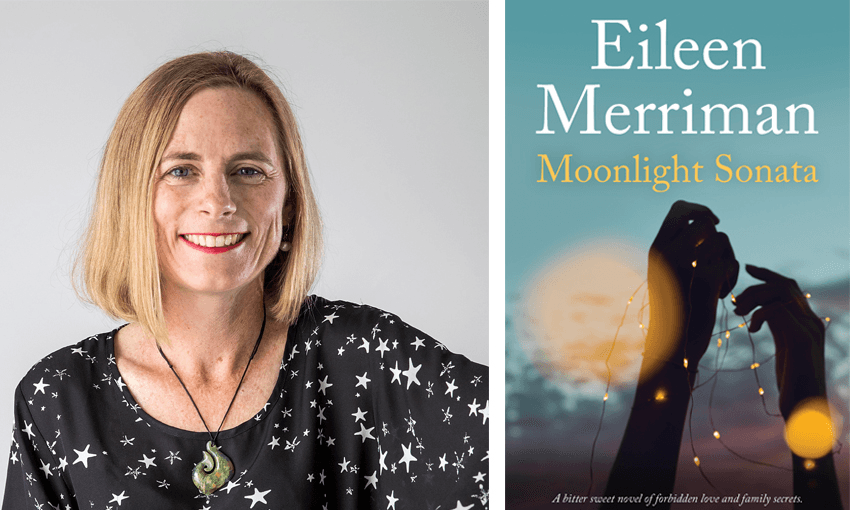

Extracted from Moonlight Sonata by Eileen Merriman (Penguin Random House NZ, $38.00), available at Unity Books.

Text © Eileen Merriman, 2019