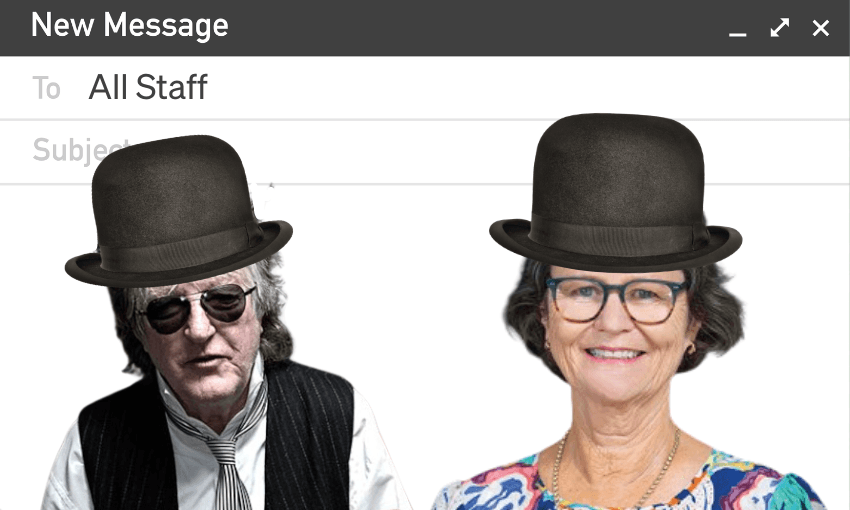

Against the backdrop of looming job cuts, an all-staff email from secretary for education Iona Holsted included Sam Hunt’s ‘Beware the Man’. Claire Mabey unpacks it.

“We’re seeing the radical decimation of the Ministry of Education, which has been forced on it by the government and executed in the most harmful way possible,” said Fleur Fitzsimons on RNZ’s Morning Report this morning, speaking in her capacity as assistant secretary at the New Zealand Public Service Association (the PSA, our largest union) on the ministry’s proposed restructure and the 700-plus jobs that will be lost because of it.

But not just yet.

The restructure is now on pause – every MoE employee who was due to finish work next week will still be employed while the PSA gets the ministry to sit down and discuss the impacts of the “inhumane and undignified approach to the cuts” that Fitzsimons said had caused “deep psychological harm through chaotic approach and mismanagement that has impacted on the ministry and the individuals involved and their families”.

That was this morning. Yesterday, on Tuesday June 18, the ministry’s boss, secretary for education Iona Holsted, sent out an all-staff email containing the line “a (repeat) interview on the weekend left me with a memory of the wonderful poems of Sam Hunt. This one sticks!” and then the full text of one of poet Sam Hunt’s most famous compositions, ‘Beware the Man’, written in 1972 (which was the year Norman Kirk shot to power: National’s term ended and Labour hooned in).

The interview Holsted refers to could well be this replay of Sam Hunt’s Mixtape on RNZ’s Music 101 over the weekend. But was Holsted’s poetic email a letter of solidarity and courage? Or was she issuing a warning?

There’s only one way to find out: let’s closely read ‘Beware the Man’ and unearth Holsted’s intentions.

First off, Sam Hunt himself. Born in Castor Bay, Auckland, in 1946, Hunt was introduced to poetry by his mum, and rubbed up against the authoritarian style of his St Peter’s College education (though he did find support and encouragement for his poetry there from a couple of teachers). Hunt’s oral style is iconic now: sprawling, idiosyncratic, tight pants, the hint always of a drunken kind of slur, like he’s perpetually on a boat pitching up and down on the waves. The tours he did with Gary McCormick are legendary: they were more like rock and roll stars. Hunt did actually make some records with The Clean’s David Kilgour. Also he’s a fan of Bob Dylan who was, at one time, a protest singer and an anti-authoritarian.

Basically, you could say that Hunt’s life’s work, his style and sensibility are distinctly anti-authority, and align with “the people”, with the workers, much more so than with “the man”.

Beware the man

Beware the man who tries to fit you out

In his idea of a hat

Dictating the colour and the shape of it.

Right, well “the man” is common-use language for authority. Often referring to an image of guys in suits who have and wield all the power that the system affords them. They “dictate” the pathways for society at large, and when and how. In the context of Holsted’s email, and this moment of high tension in the MoE workers v government-dictated cuts, I’d say we could safely say that here, “the man” could read as “the government”. Because it’s their cost-cutting directive that is affecting all the hats: how they’re worn and who gets to wear one.

There’s a slight chance that Holsted is referring to the PSA as “the man”, which would be ironic on a number of levels. But it’s far more likely she is sticking with tradition and assigning “the man” accurately.

But what about the hat? What do they symbolise? Well, we have that saying “with my [insert job title/role/occupation] hat on”, which is a way of indicating that we all have many obligations to fulfil in our lives and each of those comes with a different set of requirements. For example, a “mum hat” is a different job to the “Ministry of Education policy adviser” hat. But whatever the hat we wear, it is defined by the reigning power from which that specific hat comes. Ideally we would design our own hats: wear what fits us best, the colours that suit us, the shape that melds to our unique skulls. We don’t want someone else to tell us how to be, especially if they’re telling us that we have to take off the hat that feeds us and makes it possible to get by in a cost of living crisis.

He takes your head and carefully measures it

Says “Of course black’s out”.

He sees himself in the big black hat.

OK, here we really go. Hunt uses “He” for “the man” which reinforces the idea that the authority is that patriarchal, empathy-free sort of ruling voice. The transaction here is creepy AF: a loaded bully snatch. “He” doesn’t take your hat, he “takes your head and carefully measures it”. This shifts the focus to the person underneath the hat: “the man” is meddling directly with the hat-wearer who stands in for “the people” affected by “the man”. When he says, “Of course black’s out” it’s pure cruelty: there’s a snide bully in those words. “The man” displays a convenient disdain for what used to be in fashion. Because “he sees himself in the big black hat”. This is about the transfer of power, or rather the taking of power: “the man” is undermining the hat wearer by first suggesting that the hat wearer needs to change, and then by saying what he currently has is no longer fashionable, when really he means “I just want it for myself”.

So you may be a member of the act

He makes for you your special coloured hat.

Beware! He’s fitting you for more than that.

Here’s where we get context for this hat exchange. “So you may be a member of the act” refers to a grander scheme, a performance. There’s that idea of dictation again, of control. “The man” is composing how he and the hat wearer will orbit each other, what role they will be playing, by manipulating the power balances, by fitting people out, by telling them what to wear, and how. There’s also an infantilising aspect to this voice: “He makes for you your special coloured hat.” This imitates the way we might speak to a child: telling them something is special, and just for them (like a lollipop before a jab in the upper arm).

The last line is a clear warning bell: “Beware! He’s fitting you for more than that.” Phwoar. Here we are asked to zoom out and get a load of the big picture. The symbolic dance between “the man” and the “you” or the hat wearer is about showing that when those in positions of authority reorganise our lives for us, refit our hats (eg our jobs is an appropriate reading in this case), it’s about changing society at large. It’s about “more” than wielding power, it’s about forcing the people to fit into their wider schemes, their grander visions.

I think Iona Holsted knows her poetry. Holsted has also defended MoE hires in the recent past, which further suggests that her appreciation of Sam Hunt is an appreciation of a voice of the people and their work. The secretary for education sent out a gesture of solidarity to a beleaguered collective of individuals who are having their hats ripped off their heads. I’m sure they got all of that and more from the unsolicited poem.